By Daniel Dunaief

In the typical process of developing cures for medical problems or diseases, researchers explore the processes and causes and then spend years searching for remedies.

Sometimes, however, the time frame for finding a solution is cut much shorter, particularly when the Food and Drug Administration has already approved a drug treatment for another problem.

This could be the case for hemorrhagic stroke. Caused by a burst blood vessel that leads to bleeding in the brain, hemorrhagic stroke represents 13 percent of stroke cases, but accounts for 50 percent of stroke fatalities.

That’s because no current treatment exists to stop a process that can lead to cognitive dysfunction or death.

A researcher with a background in cancer and stroke, Ke Jian “Jim” Liu, Professor of Pathology and Associate Director or Basic Science at the Stony Brook Cancer Center who joined Stony Brook University in 2022, has found a mechanism that could make a hemorrhagic stroke so damaging.

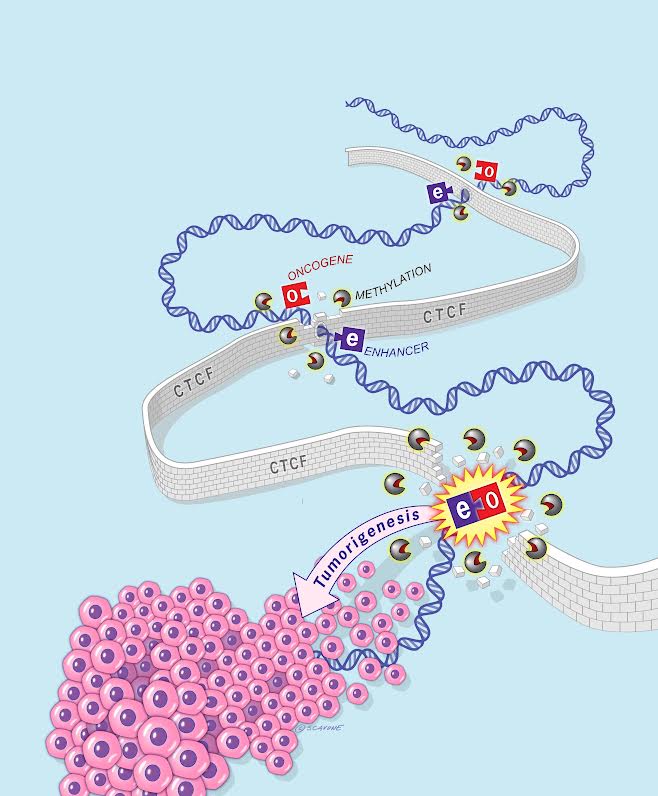

When a blood vessel in the brain bursts, protoporphyrin, a compound that attaches to iron to form the oxygen carrying heme in the blood, partners up with zinc, a similar metal that’s in the brain and is released from neurons during a stroke. This combination, appropriately called zinc protoporphyrin, or ZnPP, doesn’t do much under normal conditions, but could be “highly toxic” in hypoxic, or low-oxygen conditions.

“We have done some preliminary studies using cellular and animal stroke models,” said Liu. “We have demonstrated on a small scale” that their hypothesis about the impact of ZnPP and the potential use of an inhibitor for the enzyme that creates it ‘is true.’”

These scientists recently received a $2.6 million grant over five years from National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, which is a branch of the National Institutes of Health.

Focusing on a key enzyme

After Liu and his colleagues hypothesized that the ZnPP was toxic in a low-oxygen environment, they honed in on ways to reduce its production. Specifically, they targeted ferrochelatase, the enzyme that typically brings iron and protoporphyrin together.

Iron isn’t as available in this compromised condition because it has a positive charge of three, instead of the usual plus two.

Liu discovered the role of zinc in research he published several years ago.

When a hemorrhagic stroke occurs, it creates a “perfect storm,” as the enzyme favors creating a toxic chemical instead of its usual oxygen carrying heme, Liu said. He is still exploring what makes ZnPP toxic.

The group, which includes former colleagues of Liu’s from the University of New Mexico, will continue to explore whether ZnPP and the enzyme ferrochelatase becomes an effective treatment target.

Liu was particularly pleased that currently approved treatments for cancer could be repurposed to protect brain cells during a hemorrhagic stroke. Indeed, with over 80 approved protein kinase inhibitors, which could work to stop the formation of ZnPP during a stroke, Liu and his colleagues have plenty of potential treatment options.

“We’re in a unique position that a clinically available drug that’s FDA approved for cancer treatment” could become a therapeutic solution for a potentially fatal stroke, Liu said.

To be sure, Liu and his colleagues plan to continue to conduct research to confirm that this process works as they suggest and that this possible therapy is also effective.

As with other scientific studies of medical conditions, promising results with animal models or in a lab require further studies and validation before a doctor can offer it to patients.

“This is an animal model, based on a few observations,” said Liu. “Everything needs to be done statistically.”

At this point, Liu is encouraged by these preliminary studies as the subjects that received an inhibitor are “running around,” he said. “You can see the difference with your own eyes. We’re excited to see that.”

Earlier hypotheses for what caused damage during hemorrhagic stroke focused on the release of iron. In research studies, however, using a chelator to bind to iron ions has produced some benefits, but they are small compared to the damage from the stroke. The chelator is “not really making any major difference,” said Liu.

The Stony Brook researcher did an experiment where he compared ZnPP with the damage from other metabolic products.

“ZnPP is several times more toxic than all the other things combined,” which is what makes them believe that ZnPP might be responsible for the damage, he said.

Proof of principle

For the purpose of the grant, Liu said the scientists were focusing on gathering more concrete evidence to support their theory. The researchers are also testing a few of the protein kinase inhibitors to demonstrate that they work.

In their preliminary studies, they chose several inhibitors based on whether the drug penetrates the blood brain barrier and that have a relatively high affinity for ferrochelatase.

“This opens the door for a new phase of the study,” Liu said. “Can we find the best drug that provides the best outcomes? We are not there yet.”

Removing zinc is not an option, as it is a part of 2 percent of the proteome, Liu said. Taking it out would “screw up the entire biological, physiological system,” he added.

Liu speculates that any future drug treatment would involve a relatively small dose at a specific time, although he recognized that any drug could have side effects.

In an uncertain funding climate in which the government is freezing some grants, Liu hopes that the financial support will continue through the duration of the grant.

“Our hope is that at the end of this grant, we can demonstrate” the mechanism of action for ZnPP and can find a reliable inhibitor, he said. “The next step would be to go to a clinical trial with an FDA-approved drug, and that would be fantastic.”