By Daniel Dunaief

Jennifer Granholm, the new secretary of the Department of Energy, is pleased with the role the 17 national laboratories has played in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic over the last year and is hopeful research from these facilities will aid in the response to any future potential pandemics.

There are “70,000 people who are spread out across America solving problems,” Granholm said in a recent press conference that highlighted the effort and achievement of labs that redirected their resources to tackle the public health threat.

The DOE is “the solutions department” and has “some of the greatest problem solvers.”

“It is super exciting to talk about this particular issue, the issue of the day, the COVID, and what the lab has been doing about it,” she added.

Granholm, who was confirmed by a Senate vote of 64-35 and was sworn in as secretary on February 25th, had previously been the Attorney General in Michigan and was the first female governor of Michigan, serving two terms from 2003 to 2011.

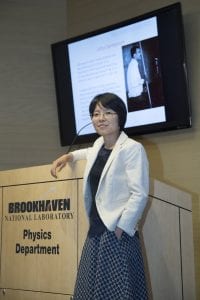

The press conference included three research leaders from national labs across the country, including Kerstin Kleese van Dam, Director of the Computational Science Initiative at Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton.

Kleese van Dam was the BNL lead for one of the five DOE teams that tackled some of the scientific challenges caused by the virus. She led the effort to inform therapeutics related to COVID-19.

The other four teams involved manufacturing issues, testing, virus fate and transport, which includes airflow monitoring, and epidemiology.

The public discussion was intended to give people a look at some of the “amazing work that you all are doing,” Granholm said.

The Department of Energy formed the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, or NVBL, to benefit from DOE user facilities, such as the light and neutron sources, nanoscience centers, sequencing, and high-performance computer facilities to respond to the threat posed by COVID-19.

Funding for NVBL enabled BNL scientists to pivot from what they were doing to address the challenge created by the pandemic, John Hill, Director of the National Synchrotron Light Source II, explained in an email.

BNL had been constructing a new facility, called the Laboratory for Biomolecular Structures, prior to the pandemic. The public health threat created by the virus, however, accelerated the time table by two months for the completion of the structure.

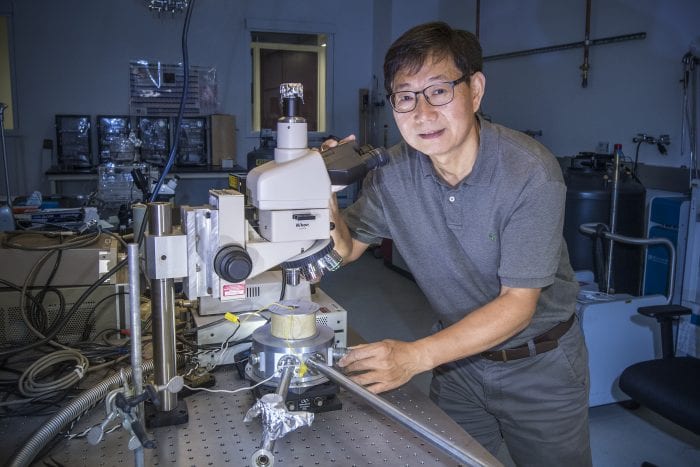

The lab has new cryo-electron microscopes that allow scientists to study complex proteins and the architecture of cells and tissues. The cryo-EM facility contributed to work on the “envelope” protein for the SARS-CoV2 virus, which causes COVID-19.

“We at BNL built a new facility which gives further capabilities to look at the virus during the pandemic,” Kleese van Dam said during the press conference. The lab prepared the facility “as quickly as possible so we could help in the effort.”

Kleese van Dam said the three light sources around the country, including the National Synchrotron Light Source II at BNL, have been working throughout the crisis with the pharmaceutical industry, helping them “refine and improve their medications.”

Indeed, Pfizer scientists used the NSLS-II facility to research certain structural properties of their vaccine. At the same time, researchers have worked on a number of promising antivirals, none of which has yet made it into clinical use.

The national laboratories, including BNL, immediately tackled some of the basic and most important questions about the virus soon after the shutdown last spring.

“There was a period last year, in the depths of the first lockdown in New York, when [the National Synchrotron Lightsource-II] was only open to COVID research,” Hill wrote in an email. “That was done both by BNL scientists and others working with our facility remotely. All other research was on hold.”

The facility reopened to other experiments in May for remote experiments, Hill continued.

Kleese van Dan explained that other projects also had delays.

“These [delays] were up front discussed with collaborators and funders and all whole heartedly supported our shift in research,” said Kleese van Dam. “Many of them joined us in this work.”

Hill said the NSLS-II continues to work on COVID-19 and that much of the work the lab has conducted will be useful in future pandemics. “We are also exploring ways to maintain preparedness going forward,” he continued.

BNL is collaborating with other groups, including private companies, to enable a robust and rapid response to future threats.

“BNL is part of a multi-lab consortium — ATOM (Accelerating Therapeutics for Opportunities in Medicine) — that aims to pursue the therapeutics work in collaboration with other agencies, foundations and industry,” Kleese van Dam wrote in an email.

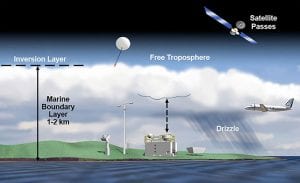

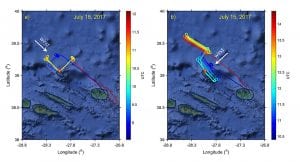

In response to a question from Granholm about the safety of schools and the study of airflow, Kleese van Dam explained that national labs like BNL regularly study the way aerosols move in various spaces.

“As a national lab, we study pollution and smoke and things like that,” Kleese van Dam said during the press conference.

The lab tested the virus in the same way, exploring how particles move to understand infections.

“When we think about this, we think about how air moves through small and confined spaces,” Kleese van Dam said. “What I breathe out will be all around you. If we were outside, the air I’m breathing out is mixed with clean and healthy air. The load of the virus particles that arrive are much smaller.”

Using that knowledge, BNL and other national laboratories did quite a few studies, including exploring the effect of using masks on the viral load.

People at numerous labs used computer simulations and practical tests to get a clearer picture of how to reduce the virus load in the air.

Granholm pledged to help share information about minimizing the spread of the virus.

“We’re going to continue to focus on getting the word out,” Granholm said. The labs are doing “great work” and the administration hopes to “make the best use of it.”