SBU tests pancreatic cancer drug discovered on-site

By Daniel Dunaief

The Stony Brook Cancer Center is seeking patients with pancreatic cancer for a phase 3 drug trial of a treatment developed by a husband and wife team at SBU.

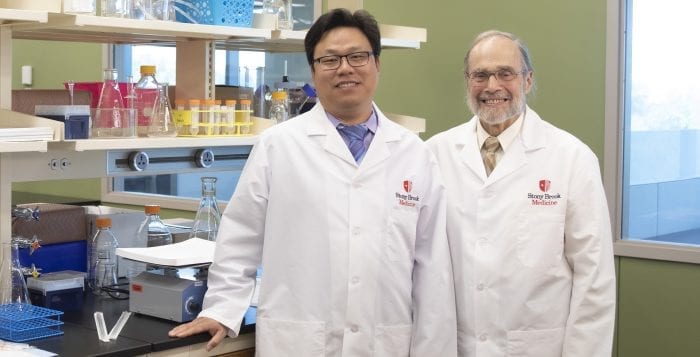

Led by Minsig Choi, the principal investigator of the clinical trial and a medical oncologist at Stony Brook Cancer Center’s gastroenterology team, the study is part of a multicenter effort to test whether a drug known as CPI-613, or devimistat, can extend the lives of people battling against a form of cancer that often has a survival rate of around 8 percent five years after its discovery.

Patients at Stony Brook will either receive the conventional treatment of FOLFIRINOX, or a combination of a FOLFIRINOX and CPI-613. An earlier study demonstrated a median survival of 20 months with the combination of the two drugs, compared with 11 months with just the standard chemotherapy.

“Pancreatic cancer is such a bad disease,” Choi said. “The overall survival is usually less than a year and life expectancy is very limited.”

Choi said the company that is developing the treatment, Rafael Pharmaceuticals, wanted Stony Brook to be a part of the larger phase 3 study because the drug was developed at the university. Indeed, Stony Brook is the only site on Long Island that is offering this treatment to patients who meet the requirements for the study.

People who have received treatment either from Stony Brook or at other facilities are ineligible to be a part of the current trial, Choi said. Additionally, patients with other conditions, such as cardiac or lung issues, would be excluded.

Additionally, the current study is only for “advanced patients with metastatic” pancreatic cancer, he said. People who have earlier forms of this cancer usually receive surgery or other therapies.

“When you’re testing new drugs, you want to start in a more advanced” clinical condition, he added.

Choi said patients who weren’t a part of the study, however, would still have other medical options.

“The clinical trial is not the only way to treat” pancreatic cancer, he said. These other treatments would include chemotherapy options, palliative care, radiation therapy and other supportive services through social workers.

Choi anticipates that the current study, which his mentor Philip A. Philip, a professor in the Department of Oncology at the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute in Detroit is leading, would likely provide preliminary results in the next 18 to 24 months.

If the early results prove especially effective, the drug may receive a fast-track designation at the Food and Drug Administration. That, however, depends on the response rate and the way patients tolerate the treatment.

At this point, Choi anticipates that most of the side effects will be related to the use of chemotherapy, which causes fatigue and weakness. The CPI-613, at least in preliminary studies, has been “pretty well tolerated,” although it, like other drug regimes, can cause upset stomachs, diarrhea and nausea, he said.

Doctors and researchers cautioned that cancer remains a problematic disease and that other drugs to treat forms of cancer have failed when they reach this final stage before FDA approval, in part because cancer can and often does develop ways to work around efforts to eradicate it.

Still, the FDA wouldn’t have approved the use of this drug in this trial unless the earlier studies had shown positive results. Prior to this broader clinical effort, patients who used CPI-613 in combination with FOLFIRINOX had a tumor response rate of 61 percent, compared with about half that rate without the additional treatment.

Paul Bingham, an associate professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Cell Biology at Stony Brook University, and his wife Zuzana Zachar, a research assistant professor and director of Master in Teaching Biology Program at the Institute for STEM Education at Stony Brook, originally invented and discovered the family of drugs that includes CPI-613.

Bingham and Zachar, who are consultants to Rafael Pharmaceuticals, “provide basic scientific support” in connection with this phase 3 trial. “When the FDA asks questions, sometimes it requires us to do basic science” to offer replies, he said.

Zachar and Bingham developed this drug because they anticipated that attacking cancer cell’s metabolism could lead to an effective treatment. Cancer requires considerable energy to continue on its deadly course. This drug, which is a lipoate analog and is an enzyme cofactor in several central processes in metabolism, tricks the disease into believing that it has sufficient energy. Interrupting this energy feedback mechanism causes the cancer cell to starve to death.

While other cells use some of the same energy feedback pathways, they don’t have the same energy demands and the introduction of the drug, which has tumor-specific effects, is rarely fatal for those cells.

The lipoate analog is a “stable version of the normally transient intermediary that lies to the regulatory systems, which causes them to shut down the metabolism of cancer cells,” Bingham said. These cells “run out of energy.”

Zachar said the process of understanding how CPI-613 could become an effective treatment occurred over the course of years and developed through an “accretion of data that starts to fill in a picture and eventually you get enough information to say that it could be” a candidate to help patients. The process is more “incremental than instantaneous.”

Bingham and Zachar are working on a series of additional research papers that reflect the way different tumors and tumor types have different sensitivities to CPI-613. They expect to publish at least one new paper this year and several more next year.

The researchers who developed this drug have had some contact with patients through the process. While they are not doctors, they are grateful that the work they’ve done has “extended and improved people’s lives,” Bingham said, and they are “grateful for that opportunity.”

Zachar added that she is “thrilled that we’ve been able to help.” She appreciates the contribution the patients make to this research because they “stepped to the line and took the risk to try this drug.”