By Daniel Dunaief

Detectives often look for the smallest clue that links a culprit to a crime. A fingerprint on the frame of a stolen Picasso painting, a shoe print from a outside a window of a house that was robbed or a blood sample can provide the kind of forensic evidence that helps police and, eventually, district attorneys track and convict criminals.

The same process holds true in the world of disease detection. Researchers hope to use small and, ideally, noninvasive clues that will provide a diagnosis, enabling scientists and doctors to link symptoms to the molecular markers of a disease and, ultimately, to an effective remedy for these culprits that rob families of precious time with their relatives.

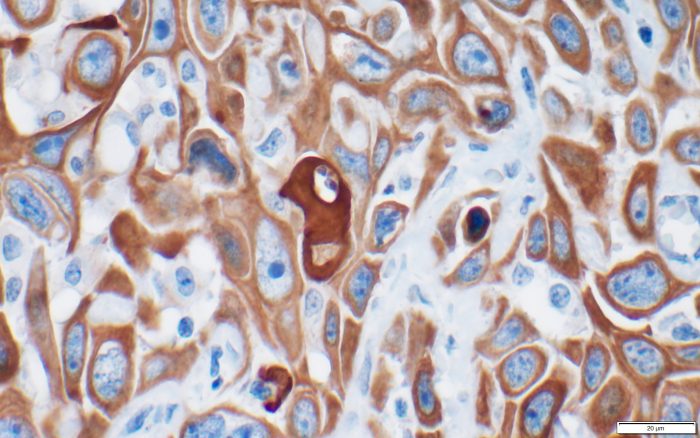

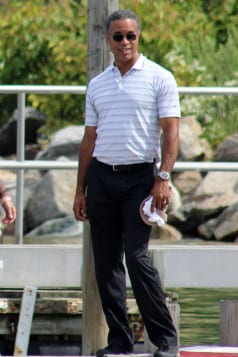

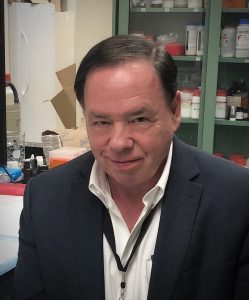

For years, Ken Shroyer, the Marvin Kuschner Professor and Chair of Pathology at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University, has been working with a protein called keratin 17.

A part of embryological development, keratin 17 was, at first, like a witness who appeared at the scene of one crime after another. The presence of this specific protein, which is unusual in adults, appeared to be something of a fluke.

Until it wasn’t.

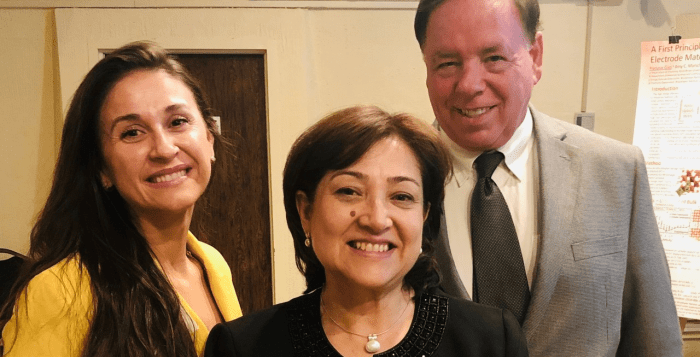

Shroyer and a former member of his lab, Luisa Escobar-Hoyos, who is now an Assistant Professor at Yale, recently published two papers that build on their previous work with this protein. One paper, which was published in Cancer Cytopathology, links the protein to pancreatic cancer. The other, published in the American Journal of Clinical Pathology, provides a potentially easier way to diagnose bladder cancer, or urothelial carcinoma.

Each paper suggests that, like an abundance of suspicious fingerprints at the crime scene, the presence of keratin 17 can, and likely does, have diagnostic relevance.

Pancreatic cancer

A particularly nettlesome disease, pancreatic cancer, which researchers at Stony Brook and Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, including CSHL Cancer Center Director David Tuveson, have been studying for years, has a poor prognosis upon diagnosis.

During a process called surgical resection, doctors have been able to determine the virulence of pancreatic cancer by looking at a larger number of cells.

Shroyer and Escobar Hoyos, however, used a needle biopsy, in which they took considerably fewer cells, to see whether they could develop a k17 score that would correlate with the most aggressive subtype of the cancer.

“We took cases that had been evaluated by needle biopsy and then had a subsequent surgical resection to compare the two results,” Shroyer said. They were able to show that the “needle biopsy specimens gave results that were as useful as working with the whole tumor in predicting the survival of the patient.”

A needle biopsy, with a k17 score that reflects the virulence of cancer, could be especially helpful with those cancers for which a patient is not a candidate for a surgical resection.“That makes this type of analysis available to any patient with a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, rather than limiting it to the small subset of cases that are able to undergo surgery,” Shroyer said.

Ultimately, however, a k17 score is not the goal for the chairman of the pathology department.

Indeed, Shroyer would like to use that score as a biomarker that could differentiate patient subtypes, enabling doctors to determine a therapy that would prove most reliable for different groups of people battling pancreatic cancer.

The recently published report establishes the foundation of whether it’s possible to detect and get meaningful conclusions from a needle biopsy in terms of treatment options.

At this point, Shroyer isn’t sure whether these results increase the potential clinical benefit of a needle biopsy.

“Although this paper supports that hypothesis, we are not prepared yet to use k17 to guide clinical decision making,” Shroyer said.

Bladder cancer

Each year, doctors and hospitals diagnose about 81,000 cases of bladder cancer in the United States. The detection of this cancer can be difficult and expensive and often includes an invasive procedure.

Shroyer, however, developed a k17 protein test that is designed to provide a reliable diagnostic marker that labs can get from a urine sample, which is often part of an annual physical exam.

The problem with bladder cancer cytopathology is that the sensitivity and specificity aren’t high enough. Cells sometimes appear suggestive or indeterminate when the patient doesn’t have cancer.

“There has been interest in finding biomarkers to improve diagnostic accuracy,” Shroyer said.

Shroyer applied for patent protection for a k17 assay he developed through the Stony Brook Technology Transfer office and is working with KDx Diagnostics. The work builds on “previous observations that k17 detects bladder cancer in biopsies,” Shroyer said. He reported a “high level of sensitivity and specificity” that went beyond that with other biomarkers.

Indeed, in urine tests of 36 cases confirmed by biopsy, 35 showed elevated levels of the protein.

KDx, a start up biotechnology company that has a license with The Research Foundation for The State University of New York, is developing the test commercially.

The Food and Drug Administration gave KDx a breakthrough device designation for its assay test for k17.

Additionally, such a test could reveal whether bladder cancer that appears to be in remission may have recurred.

This type of test could help doctors with the initial diagnosis and with follow up efforts, Shroyer said.“Do patients have bladder cancer, yes or no?” he asked. “The tools are not entirely accurate. We want to be able to give a more accurate answer to that pretty simple question.”