By Victoria Espinoza

Young students in the Northport-East Northport school district were given a firsthand account of one of the most pivotal and horrific periods in human history.

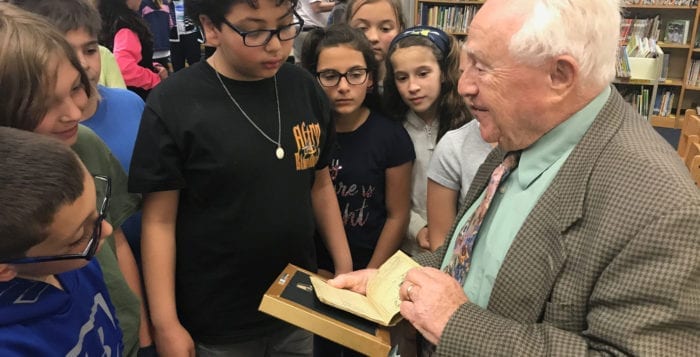

Holocaust survivor Werner Hess, 96, spoke to Northport elementary students last week to share his story and encourage attendees to be kind and accepting of one another.

Hess’ life changed when Hitler came to power while he was living in Frankfurt, Germany. His mother was able to help him escape to England in 1939 and, Hess eventually arrived in the United States in 1940. He talked about how the events leading up to World War II were encouraged by racial hate speech, and isolating and mistreating certain groups of people.

“These horrible sufferings must not be forgotten, and the lessons of the Holocaust must not be diminished into just a footnote in history,” Hess said at Dickinson Avenue Elementary School May 26. “We must educate generations…and combat all forms of racial, religious and ethnic hatred before it is too late.”

Hess told the children to imagine living how they are now, except being forced to no longer see their friends, and family members being sent off to concentration camps to do slave labor. Hess himself went through that reality when he was about the same age as the fourth- and fifth-graders he spoke to.

Hess’ family had lived in Germany for generations, and his grandparents fought for Germany in World War I. Hess had plans to go to college and become an accountant, however he said this became impossible once Jewish people were no longer allowed to attend college in Germany. This led Hess to drop out of school and learn how to make women’s handbags in a factory in his town. However, soon enough the government shut down the factory, and Hess’ Christian supervisor helped him get work elsewhere undercover, where he was hidden from inspectors.

The only part of Hess’ childhood the Northport students could relate to was that he was playing on a local soccer team. He was the only Jewish boy on the team. He had played for years, however one Sunday in 1935 he was told by the coach he could no longer play due to his religion.

“Quite a blow to a 14-year-old boy,” he said.

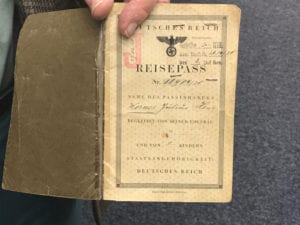

Eventually Hess said Jewish-owned stores were closing down, with signs on their windows saying, “owned by Jews, don’t shop from Jews.” Books written by Jews were burned in his town, statues erected for well known Jewish leaders were destroyed and Jewish names were removed from street signs. Hess lost his citizenship, and was given a passport with a large red ‘J’ on it to identify his religion. Hess said he watched synagogues, including the temple where his bar mitzvah was held, Jewish owned stores, including his parent’s fish store and homes burned down by the government, and Jewish citizens rounded up and taken to concentration camps. He saw German troops marching through his streets singing, “Jewish heads must roll, Jewish blood must be spilt.”

Gestapo officers came to Hess’ house to arrest his father and bring him to a concentration camp.

“We are all created in the image of God, you may not like each person you meet in your life, that does not mean you must hate an entire race, ethnic group or religion. You must respect the human rights of everyone.”

—Herner Wess

“After they were convinced that my father was sick and dying, they asked for me,” he said. “I was hiding in the attic of the apartment we lived in. They told my mother I should report to them when I returned home or else I would be killed on site. Trembling and with tears in her eyes, my mother came to my hiding place and sent me off to the designated assembly point.”

When Hess arrived at the train station he was told the last round of transfers just left and they would get him on the next train, but it never showed and he was sent home.

“Whether it was just luck or higher powers that protected me I don’t know,” he said.

When Hess was 17-years-old, shortly after his father died, he was able to escape Germany and fled to England.

“Saying goodbye to my mother at the train station in Frankfurt was very, very difficult,” he said. “Put yourself in my position. Having just lost my father, saying goodbye to my mother and not being assured if we would ever see each other again. Forced to leave family and friends, and head to a foreign country where I didn’t speak the language.”

He said traveling to England was not easy, and people were constantly taken off trains by border guards and shipped to concentration camps to be murdered — including his aunt, uncle and cousins.

Eventually Hess was able to bring his mother to England and in 1940 he left for America. Three years later he was drafted into the Army.

“It was not only the Jewish people who suffered during this time,” Hess said. “Millions of innocent people of all religions were killed. We are all created in the image of God, you may not like each person you meet in your life, that does not mean you must hate an entire race, ethnic group or religion. You must respect the human rights of everyone.”

After Hess finished speaking students asked him dozens of questions about his life, what soccer position he played, what it was like making handbags, what he misses about Germany and if he’s ever been back. Students looked in awe at his original passport he used to travel out of Germany, and saw the red ‘J‘ and Swastika symbols covering the front.

“In those 12 years he [Hitler] turned one of the most civilized nations in the world into one of the most barbarous of all time,” he said. “Please do not bully your friends, because everyone is different, but that doesn’t mean you need to hate them. So be nice to each other.”