D. None of the Above: Considering the ways we choose to define ourselves

By Daniel Dunaief

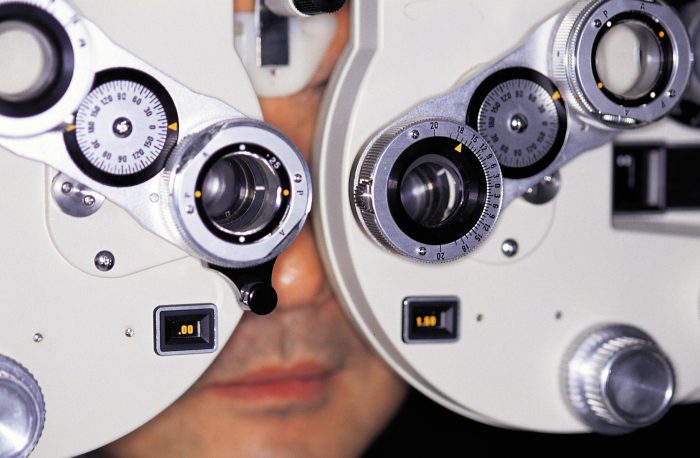

Have you ever sat in the eye doctor’s chair and had them shift from one lens to another, asking you if A or B is better or if 1 or 2 is clearer?

I did that many times growing up, particularly because my father was an ophthalmologist.

Oftentimes, even now, I’m not exactly sure whether the first image or second is better. In fact, I asked my father to let me see them again. I could hear him groan as I said, “One, no, no, two, no, wait, one.”

The same subtle differences sometimes define who we are and how we see ourselves.

Sometimes, the question of our identity is simple, at least to us. Are we American and do we live in the Middle Atlantic States?

Other questions also might elicit reflective responses. Are we religious and, if so, do we celebrate Christmas, Hannukah, or Kwanza? Or, maybe we’re not religious at all, and we think of life and ourselves outside the structure of an organized religion.

We also might define ourselves by our race or our combination of races. I had a close friend in college who was so many races that she said she could check off every box on each survey to reflect her mixed heritage.

But, then, when we define ourselves as part of a group, whether it’s a race, religion, political affiliation or other, what does it mean to meet someone or interact with someone from a different group? If we’re a Republican and someone else is a Democrat, should we behave as if we are the Montagues and the Capulets?

Does the fact that they are different mean we don’t have to be respectful of them or that we need to protect our own first before considering their needs?

Surely, such insular, tribal and protective thinking should violate our sense of right and wrong. Can we prejudge people or suggest that we care less about them because they weren’t born with some of the same elements that define us?

Several of the ways we identify ourselves don’t typically involve choices. I can’t choose to be much taller, even if I might want to be, and I can’t choose to be Taiwanese, even if I have many close friends who trace their roots to Taiwan.

We have choices in our identity that affect our behavior and define us.

We might, for example, choose not to be a bystander, but, rather a defender. People don’t, or shouldn’t, wake up in the morning and hope to witness someone bully someone else and feel gratified that they observed cruelty.

Perhaps, we might consider ourselves protectors or active community members. Remembering this part of our identity, we might be more inclined to help.

We might also choose to identify ourselves as grateful. We might choose a host of adjectives to describe ourselves — smart, flexible, sympathetic, understanding. Ultimately, through our thoughts, words and actions, we can demonstrate whether those descriptions apply or whether our self-identification is a mismatch with our behaviors.

Conflicts arise in us when one part of our identity is at odds with another. We might, for example, want to help others, even though we might realize doing so comes with risk to ourselves.

Standing up for someone at the lower end of the social pecking order might cause a bully to turn his attention to us. We might run the risk of injury or worse by trying to help others in dangerous situations.

At those moments, we can be grateful to those among us who protect us against all kinds of threats, who join the armed forces, or the police or firefighters.

On this, the day before Veterans Day and two weeks before Thanksgiving, we can be thankful for all those people who contribute to our lives and to our country.