By Daniel Dunaief

In the era of social media, people reveal a great deal about themselves, from the food they eat, to the people they see on a subway, to the places they’ve visited. Through their own postings, however, people can also share elements of their mental health.

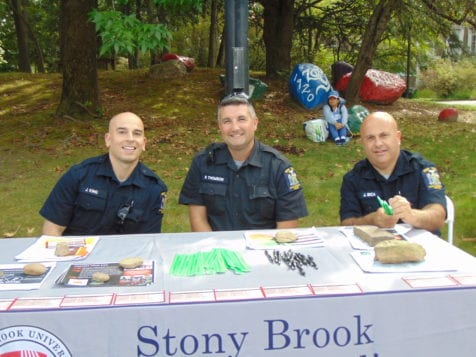

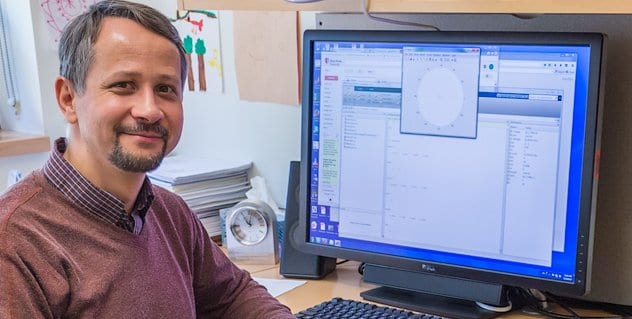

In a recent study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Andrew Schwartz, an assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science at Stony Brook University, teamed up with scientists at the University of Pennsylvania to describe how the words volunteers wrote in Facebook postings helped provide a preclinical indication of depression prior to a documentation of the diagnosis in the medical record.

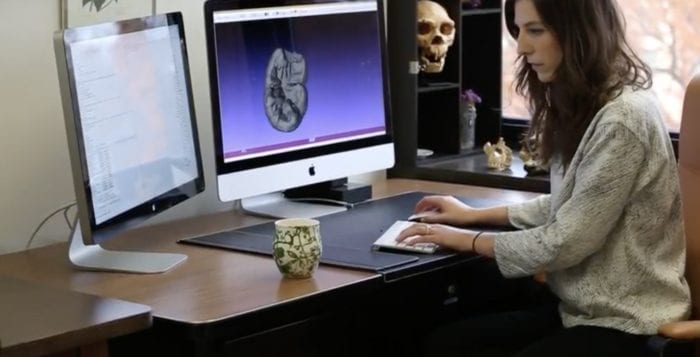

Using his background in computational linguistics and computational psychology, Schwartz helped analyze the frequency of particular words and the specific word choices to link any potential indicators from these posts with later diagnoses of depression.

Combining an analysis of the small cues could provide some leading indicators for future diagnoses.

“When we put [the cues] all together, we get predictions slightly better than standard screening questionnaires,” Schwartz explained in an email. “We suggest language on Facebook is not only predictive, but predictive at a level that bears clinical consideration as a potential screening tool.”

Specifically, the researchers found that posts that used words like “feelings” and “tears” or the use of more first-person pronounces like “I” and “me,” along with descriptions of hostility and loneliness, served as potential indicators of depression.

By studying posts from consenting adults who shared their Facebook statuses and electronic medical record information, the scientists used machine learning in a secure data environment to identify those with a future diagnosis of depression.

The population involved in this study was restricted to the Philadelphia urban population, which is the location of the World Well-Being Project. When he was at the University of Pennsylvania prior to joining Stony Brook, Schwartz joined a group of other scientists to form the WWBP.

While people of a wide range of mental health status use the words “I” and “me” when posting anecdotes about their lives or sharing personal responses to events, the use of these words has potential clinical value when people use them more than average.

That alone, however, is predictive, but not enough to be meaningful. It suggests the person has a small percentage increase in being depressed but not enough to worry about on its own. Combining all the cues, the likelihood increases for having depression.

Schwartz acknowledged that some of the terms that contribute to these diagnoses are logical. Words like “crying,” for example, are also predictive of being depressed, he said.

The process of tracking the frequency and use of specific words to link to depression through Facebook posts bears some overlap with the guide psychiatrists and psychologists use when they’re assessing their patients.

The “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” typically lays out a list of symptoms associated with conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or depression, just to name a few.

“The analogy to the DSM and how it works that way is kind of similar to how these algorithms will work,” Schwartz said. “We look at signals across a wide spectrum of features. The output of the algorithm is a probability that someone is depressed.”

The linguistic analysis is based on quantified evidence rather than subjective judgments. That doesn’t make it better than an evaluation by mental health professional. The algorithm would need more development to reach the accuracy of a trained psychologist to assess symptoms through a structured interview, Schwartz explained.

At this point, using such an algorithm to diagnose mental health better than trained professionals is a “long shot” and not possible with today’s techniques, Schwartz added.

Schwartz considers himself part computer scientist, part computational psychologist. He is focused on the intersection of algorithms that analyze language and apply psychology to that approach.

A person who is in therapy might offer an update through his or her writing on a monthly basis that could then offer a probability score about a depression diagnosis.

Linguistic tools might help determine the best course of treatment for people who have depression as well. In consultation with their clinician, people with depression have choices, including types of medications they can take.

While they don’t have the data for it yet, Schwartz said he hopes an algorithmic assessment of linguistic cues ahead of time may guide decisions about the most effective treatment.

Schwartz, who has been at SBU for over three years, cautions people against making their own mental health judgments based on an impromptu algorithm. “I’ve had some questions about trying to diagnose friends by their posts on social media,” he said. “I wouldn’t advocate that. Even someone like me, who has studied how words relate to mental health, has a hard time” coming up with a valid analysis, he said.

A resident of Sound Beach, Schwartz lives with his wife Becky, who is a music instructor at Laurel Hill Middle School in Setauket, and their pre-school-aged son. A trombone player and past member of a drum and bugle corps, he met his wife through college band.

Schwartz grew up in Orlando, where he met numerous Long Islanders who had moved to the area after they retired. When he was younger, he used to read magazines that had 50 lines of computer code at the back of them that created computer games.

He started out by tweaking the code on his own, which drove him toward programming and computers.

As for his recent work, Schwartz suggested that the analysis is “often misunderstood when people first hear about these techniques. It’s not just people announcing to the world that they have a condition. It’s a combination of other signals, none of which, by themselves, are predictive.”

Understanding the basic science of how genes in individual cells respond to temperature differences could have broad applications. In agriculture, farmers might need to know how genes or gene circuits that provide resistance to a pathogen or drought tolerance react when the temperature rises or falls.

Understanding the basic science of how genes in individual cells respond to temperature differences could have broad applications. In agriculture, farmers might need to know how genes or gene circuits that provide resistance to a pathogen or drought tolerance react when the temperature rises or falls.