By Daniel Dunaief

Instead of flying a plane through clouds and gathering data during a three to five second window of time, researchers at Brookhaven National Laboratory are one of three teams proposing constructing a cloud chamber.

This new research facility would allow them to control the environment and tweak it with different aerosols, enabling them to see how changes affect drizzle formation.

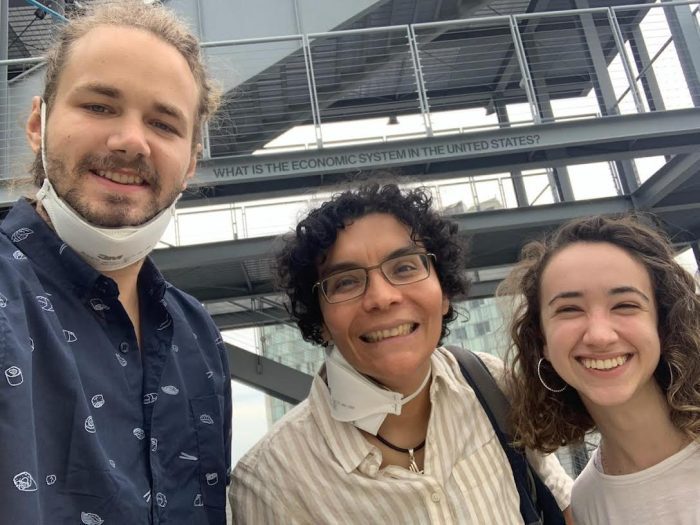

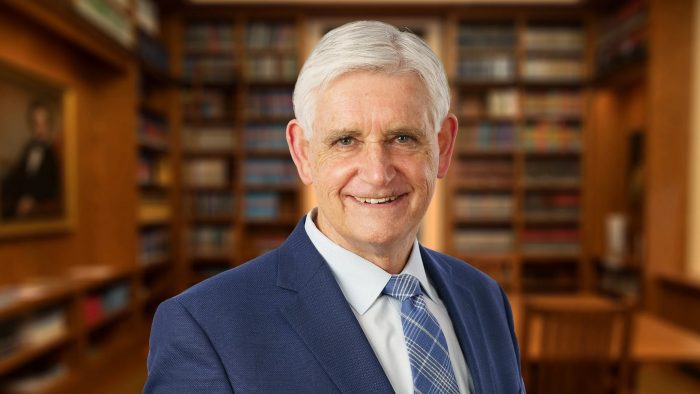

“This is fascinating,” said JoAnne Hewett, Director of BNL and a self-professed “science geek.”

Hewett, whose background is in theoretical physics and who came to BNL from SLAC National Accelerator Lab in Menlo Park, California, has been the director of the Upton-based lab since April of 2023.

In a celebrity podcast interview, which will be posted on TBR News Media’s website (tbrnewsmedia.com) and Spotify, Hewett addressed a wide range of issues, from updates on developing new technologies such as the Electron Ion Collider and the construction of buildings, to the return of students to the long-awaited reopening of the cafeteria.

The U.S. Department of Energy is currently considering the proposals for the cloud chamber and has taken the first steps towards initiating the project.

Hewett, who is the first woman to lead the national lab in its 77-year history, is hoping the winner will be announced this year.

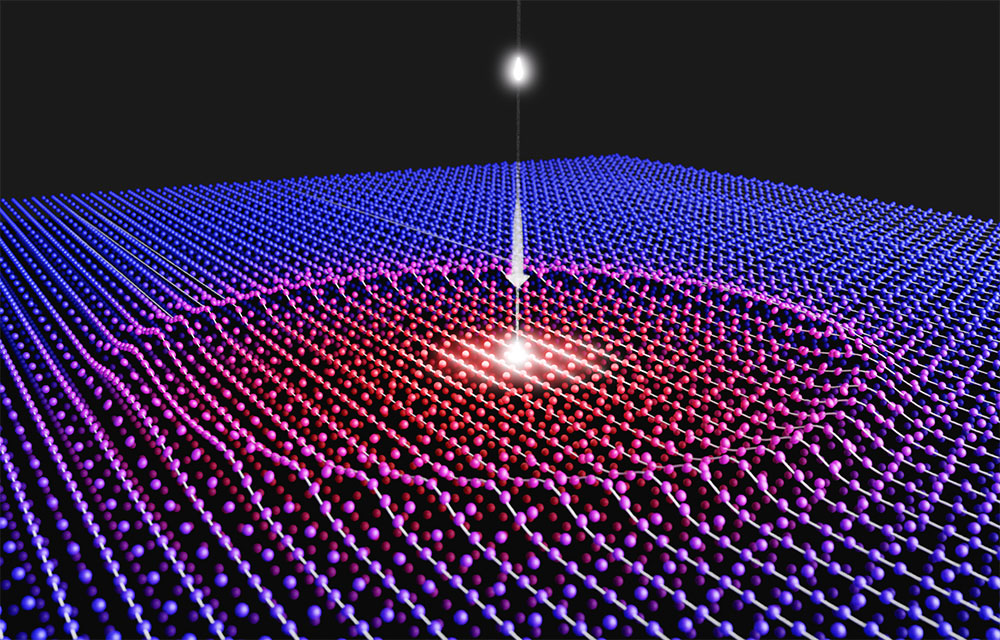

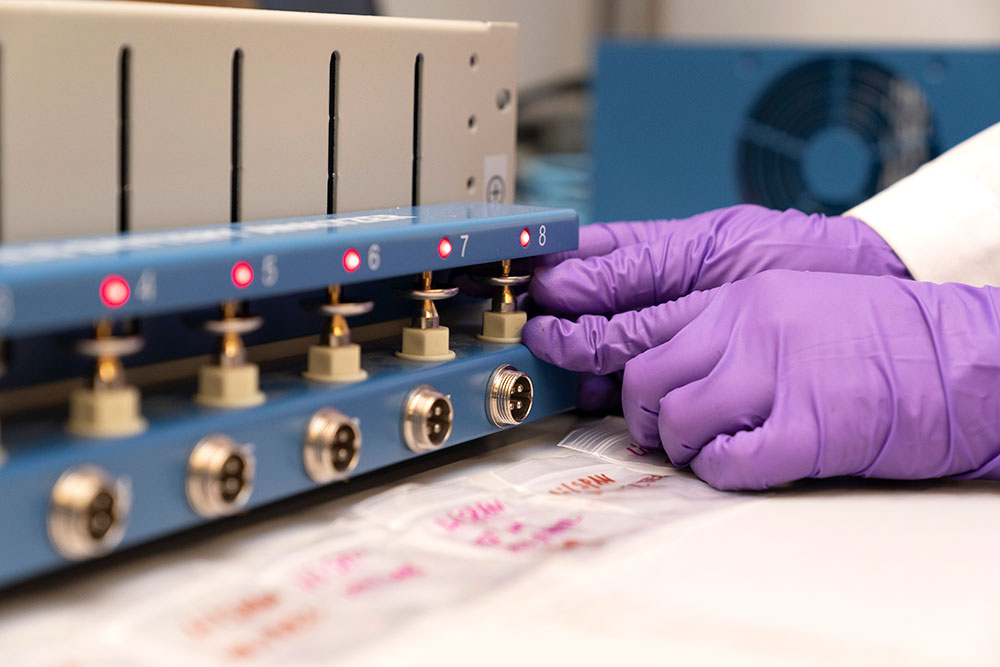

More x-ray tools

In a discussion about the National Synchrotron Lightsource II, which is a circular electron accelerator ring that sends x-rays into the specialized beamlines, Hewett described a study at the recently opened High Energy X-ray Scattering beamline, or HEX.

The state-funded HEX, which is designed for battery research, recently hosted an experiment to examine the vertebrae from Triceratops.

The NSLS-II, which opened a decade ago and has produced important results in a range of fields, will continue to add beamlines. BNL recently received approval to build another eight to 12 beamlines, depending on available funding. The lab will add one beamline in 2025 and another two in 2026.

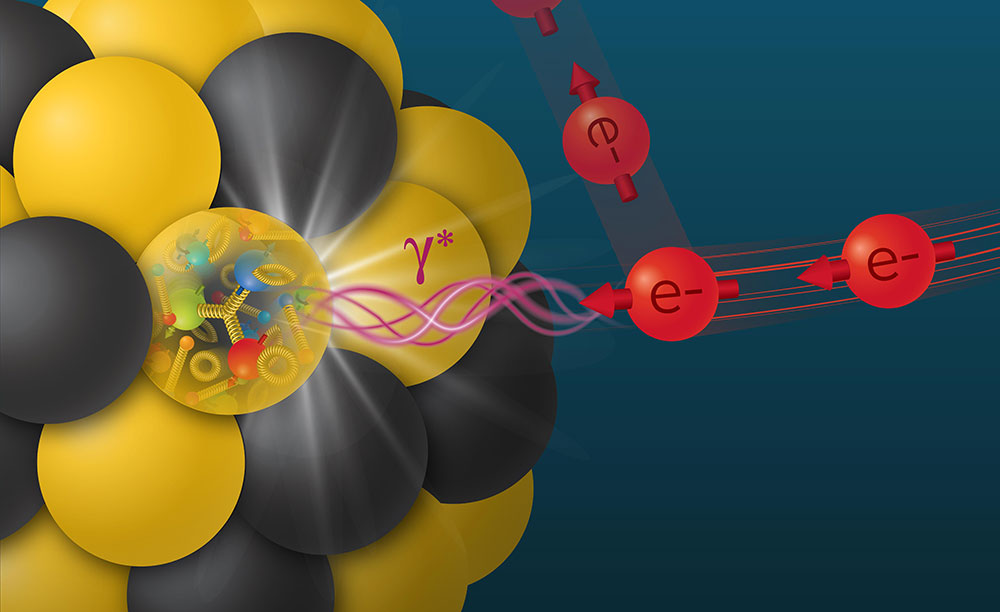

Electron-Ion Collider

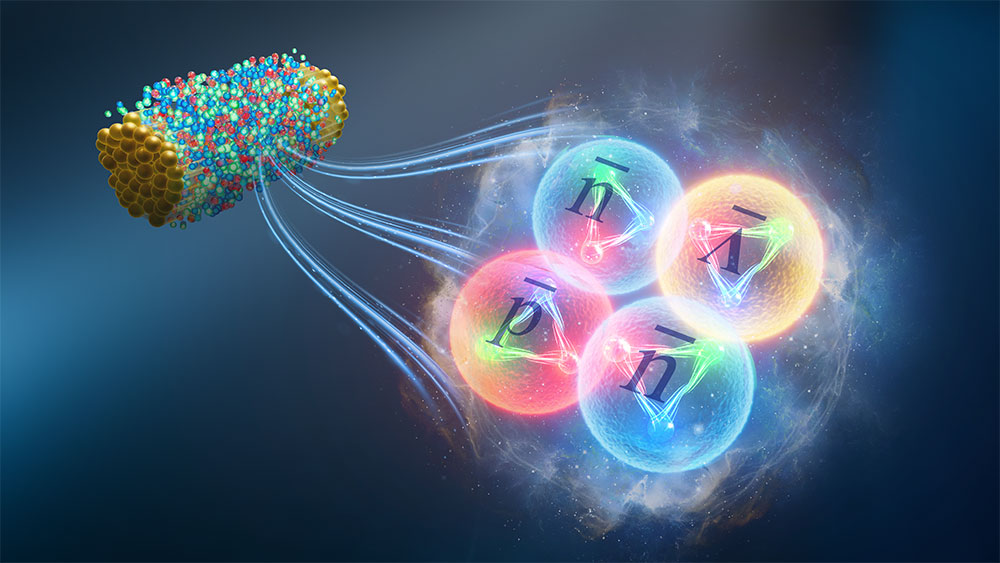

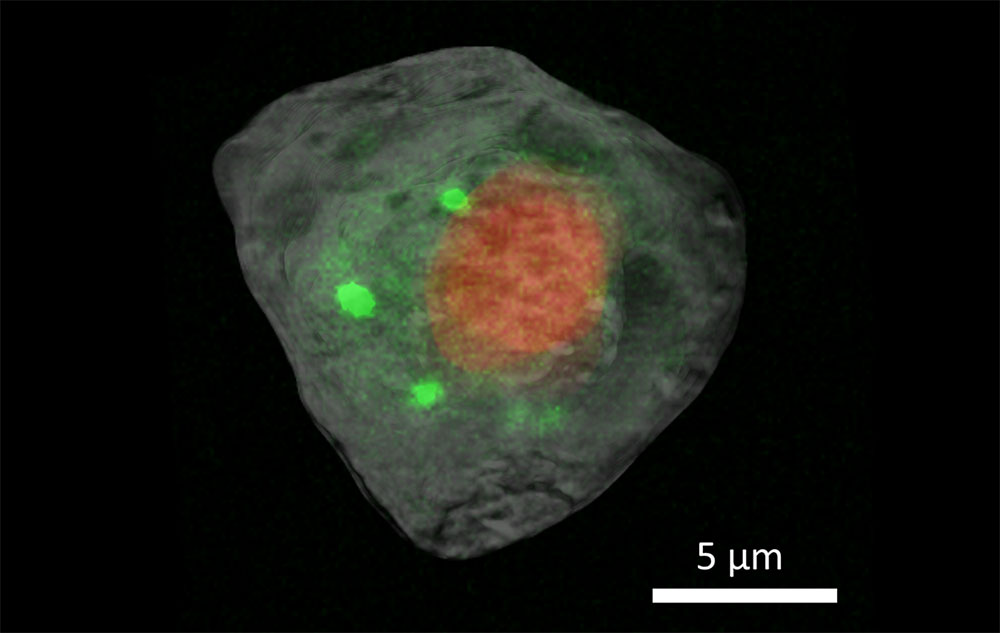

BNL, meanwhile, is continuing to take important steps in planning for an Electron-Ion Collider (EIC), an ambitious $2.8 billion project the lab won the rights to construct.

The collider, which will reveal secrets of the quarks and gluons that make up atoms, will start construction in 2026 and is expected to generate data sometime in the early 2030’s.

As groups of scientists develop plans for the EIC, they apply to the government to reach various milestones.

In March of this year, the lab met a hurdle called CD3A, which provided $100 million in funding for long lead procurements for some of the parts for the 2.4 mile circumference particle collider.

The next review, called CD3B, will be in early January and will involve $50 million in funding.

The funding for these steps involves ordering parts that the lab knows will be necessary.

The EIC will address five key questions, including how does a proton acquire its spin, what is the nature of dense gluon matter, how do quarks and gluons interact within a nucleus, what is the role of gluons in generating nuclear binding energy, and how do the properties of a proton emerge from its quark and gluon constituents.

Researchers expect the results to have application in a wide range of fields, from materials science, to medicine, to creating tools for complex simulations in areas including climate change.

Return of students

After the Covid pandemic shut down visits from area primary schools, students are now returning in increasingly large numbers.

In 2023, around 22,000 students had a chance to find scientific inspiration at BNL, which is starting to approach the pre-pandemic levels of around 30,000.

School buses come to the science learning center on the campus almost every day.

In addition, BNL hosted a record number of student internships, which are typically for college-age students.

In addition to inspiring an understanding and potentially building careers in science, BNL is now opening a new facility. The science users and support center, which is just outside the gate for the lab, is a three-story building with meeting room space.

“It’s going to be a one-stop-shop” for visiting scientists who come to the lab, Hewett said. Visiting scientists can take care of details like badging and lodges, which they previously did in separate buildings.

Additionally, for staff and visitors, BNL reopened a cafeteria that had been closed for five years. The cafeteria will serve breakfast and lunch with hot food.

“That’s another milestone for the laboratory,” Hewett said. With the extended time when the cafeteria was closed, just about everything will be new on the menu. The reopening of the facility took years because of “all the legalese” in the contract, she added.

A new vision

Hewett spent the first nine months of her tenure getting to know the people and learning the culture of the lab.

She suggested she has a new vision that includes four strategic initiatives. These are: the building blocks of the universe, which includes the Electron-Ion Collider; leading in discovery with light-enabled science, which includes the National Synchrotron Lightsource II; development of the next generation information sciences, including quantum information sciences, microelectronics and artificial intelligence; and addressing environmental and societal challenges.

As for the political landscape and funding for science, Hewett suggested that new administrations always have a change in priorities.

“We’re in the business of doing science,” she said. “Science does not observe politics. It’s not red or blue: it’s just facts.”

She suggested that generally, traditional basic research tends to do fairly well.

The BNL lab director, however, is “always making a concerted effort to justify why this investment [of taxpayer dollars] is necessary,” she said. “That’s not going to change one bit.”

After a recent visit to Capitol Hill, Hewett described her relationship with the New York delegation as “great.” She appreciates how the division that affects people’s perspectives in different parts of the world and that has led to conflicts doesn’t often infect scientists or their goals.

In the field of particle physics, “you have Israelis and Palestinians literally working together side by side,” she said. “It all comes to down to the people doing the science and not the government they happen to live under.”

Hewett also continues to believe in the value of diverse experience in the workplace. “We need the best and the brightest,” she said. “I don’t care if they’re pink with purple polka dots: we want them here at the laboratory doing science for us. We want to develop the workforce of the future.”

Adding key hires

As Hewett has settled into her role, she would like to fill some important staff functions. “This is really two or three jobs that I have to get done in the time it takes to do one job,” she said. “A chief of staff is very much needed to help move some of these projects along.”

Additionally, she is looking for someone to lead research partnerships and technology transfer. “As you do the great science, you want to be able to work hand in hand with industry in order to do the development of that science,” she said.

She said this disconnect between research and industry was known as the “Valley of Death.” Institutions like BNL “do fundamental science and industry has a product, and you don’t do enough of the work to match the two with each other.”