By Daniel Dunaief

In a world filled with disagreements over everything from presidential politics to parking places, numbers — and particularly constants — can offer immutable comfort, as people across borders and political parties can find the kind of common ground that make discoveries and innovations possible.

Many of these numbers aren’t simple, as anyone who has taken a geometry class would know. Pi, for example, which describes the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter, isn’t just 3 or 3.14.

In classes around the world, people challenge their memory of numbers and sequences by reciting as many digits of this irrational number as possible. An irrational number can’t be expressed as a fraction.

These irrational numbers can and do inform the world well outside of textbooks and math tests, making it possible for, say, electromagnetic radiation to share information across a parallel world or, in earlier parlance, the ether.

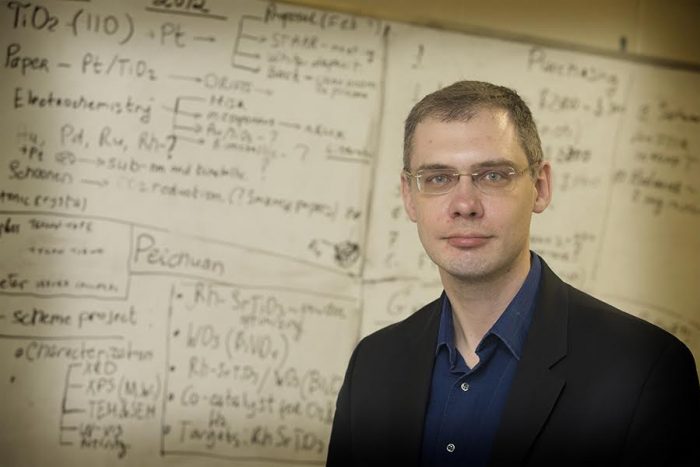

“All electronic communication is made up of waves, sines and cosines, that are defined and evaluated using pi,” said Alan Tucker, Toll Distinguished Teaching Professor in the Department of Applied Mathematics and Statistics at Stony Brook University. The circuits that send and receive information are “based on calculations using pi.”

Scientists can receive signals from the Voyager spacecraft, launched in 1977 and now over seven billion miles away, thanks to the ability to tune a circuit using math that relies on pi and numerous mathematical formulas where the sensitivity to the signal is infinite.

The signal from the spacecraft, which is over 16 years older than the average-aged person on the planet, takes about 10 hours to travel back and forth.

“Think of 1/x, where x goes to 0,” explained Tucker. “Scientists have taken that infinity to be an infinite multiplier of weak signals that can be understood.”

Closer to Earth, the internet, radio waves and TV, among myriad other electronic devices, all use generated and decoded calculations using pi.

“All space has an unseen mathematical existence that nobody can see,” said Tucker. “These are heavily based on calculations involving pi.”

Properties of nature

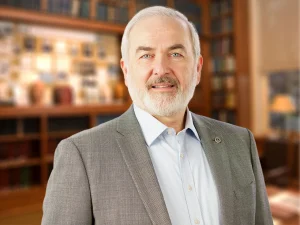

Constants reflect the realities of the world. They have “a property that is fundamental and absolute and that no one could change,” said Steve Skiena, Distinguished Teaching Professor of Computer Science at Stony Brook University. “The reason people discovered these constants as being important is because they are relating things that arise in the world.”

While pi may be among the best known and most oft-discussed constant, it’s not alone in measuring and understanding the world and in helping scientists anticipate, calculate and understand their experiments.

Chemists, for example, design reactions using a standard unit of measure called the mole, which is also called Avogadro’s number for the Italian physicist Amedeo Avogadro.

The mole provides a way to balance equations, enabling chemists to determine exactly how much of each reactant to combine to get a specific amount of product.

This huge number, which is often expressed as 6.022 times 10 to the 23rd power, represents the number of atoms in 12 grams of carbon 12. The units can be electrons, ions, atoms or molecules.

“Without Avogadro’s number, it would be impossible to determine the ratio of particular reactants,” said Elliot Smith, a postdoctoral researcher at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory who works in John Moses’s lab. “You could take an educated guess, but you wouldn’t get good results.”

Smith often uses millimoles, or 1/1000th of a mole, in the chemical reactions he does.

“If we know the millimoles of each reactant, we can calculate the expected yield,” said Smith. “Without that, you’re fumbling in the dark.”

Indeed, efficient chemical reactions make it possible to synthesize greater amounts of some of the pharmaceutical products that protect human health.

Moles, or millimoles, in a reaction also make it possible to question why a result deviated from expectations.

Almost the speed of light

Physicists use numerous constants.

“In physics, it is inescapable that you will have to deal with some of the fundamental constants,” said Alan Calder, Professor of Physics and Astronomy at Stony Brook University.

When he models stellar explosions, he uses the speed of light and Newton’s gravitational constant, which relates the gravitational force between two objects to the product of their masses divided by the square of the distance between them.

The stars Calder studies are gas ball reactions that also involve constants.

Stars have thermonuclear reactions going on in them as they evolve. Calder uses reaction rates that depend on local conditions like temperature, but there are constants in these.

Calder’s favorite number is e, or Euler’s constant. This number, which is about 2.71828, is useful in calculating interest in a bank account as well as in understanding the width of successive layers in a snail shell among many other phenomena in nature.

Electron Ion Collider

The speed of light figures prominently in the development and calculations at Brookhaven National Laboratory as the lab prepares to build the unique Electron Ion Collider, which is expected to cost between $1.7 billion and $2.8 billion.

The EIC, which will take about 10 years to construct, will collide a beam of electrons with a beam of ions to answer basic questions about the atomic nucleus.

“It’s one of the most exciting projects in the world,” said Daniel Marx, an accelerator physicist in the Electron Ion Collider accelerator design group at BNL.

At the EIC, physicists expect to propel the electrons, which are 2,000 times lighter than protons, extremely close to the speed of light. In fact, they will travel at 99.999999 (yes, that’s six nines after the decimal point) of the speed of light, which, by the way, is 186,282 miles per second. That means that light can circle the globe 7.48 times per second.

The EIC will increase the energy of ions to 99.999% of the speed of light. With only three nines after the decimal, the protons will be traveling at a slower enough speed that the designers of the collider will make the proton ring about 4 inches shorter over 2.4 miles to ensure that the protons and electrons arrive at exactly the same time.

The EIC will attempt to answer questions about the mass and spin of the nucleus. They hope to understand what happens with dense systems of gluons. By accelerating nuclei or protons to higher energies, they will get more gluons and will look for evidence of gluon saturation.

“The speed of light is absolutely fundamental to everything we do,” said Marx because it is fundamental to relativity and the particles in the accelerator are relativistic.

As for constants, Marx suggested that its value might look like a row of random numbers, but if those numbers are a bit different, that could “revolutionize” an understanding of physics.

In addition to a detailed understanding of atomic nuclei, the EIC could also lead to new technologies.

When JJ Thomson discovered the electron, he toasted it by saying, “may it never be of use to anyone.” That, however, is far from the case, as the electron is at the heart of electronics.

As for pi, Marx, like many of his STEM colleagues, appreciates this constant.

“Once you look at the mathematical statement of pi, and how it relates in various ways to other quantities in math and physics, it deepens your appreciation of how beautiful the whole universe is,” Marx said.