By Kenneth Brady

Gene Marvey could not stop thinking about the magazine article that he had just read. The story described how communities across America were reviving their failing business districts by following a simple plan. The same approach, thought Marvey, might succeed in rejuvenating the commercial area of Port Jefferson where he had a store.

“Old Towns Come Alive,” the article that had caught Marvey’s imagination, appeared in the March 1965 issue of the Rotarian and featured the work of Dr. Milton S. Osborne who had revitalized 42 communities in the United States.

Known as the “village restorer,” Osborne showed shop owners easy ways to dress up the facades of their establishments. The face lifting did not involve any structural changes or major expenditures, guaranteed local control over the project and maintained the architectural integrity of the subject area.

Marvey shared Osborne’s ideas with Port Jefferson’s mayor, Clifton “Kip” Lee and the village trustees, who voted unanimously to invite Osborne to Port Jefferson for a consultation and to underwrite the attendant fees.

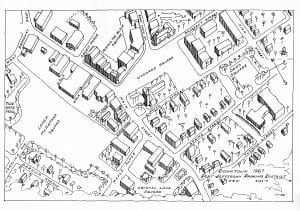

Osborne’s method was simple: each merchant submitted a photo of his storefront. Osborne then prepared a sketch of the shop’s remodeled façade which served as a guide for the suggested renovations.

For $500 to $1,000 per building, estimated Osborne, a typical Port Jefferson merchant could reface his store by merely replacing shutters, hanging flower boxes, adding wrought iron railings, installing mullions and painting the shop’s exterior in harmonious colors.

Photo from the Michael F. Lee Collection

These actions, explained Osborne, would preserve and enhance what he deemed was the semi-colonial character of the village. Osborne cautioned, however, that the effort would only succeed if there was cooperation between government and the business community.

The Greater Port Jefferson Chamber of Commerce enthusiastically endorsed Osborne’s plan and formed a committee charged with implementing what became known as Project Rejuvenation.

With a target date of July 4, 1967 set for the plan’s completion, work on remodeling Port Jefferson’s storefronts began in earnest. Davis Comfort Corporation, fuel oil dealers on East Broadway, was the first firm to reface its building. Frank Hocker and Son, real estate and insurance agents on Main Street, was the second and Kella’s Steak House, located on Main Street a stone’s throw from the railroad station, was the third.

Opening in 1903, the Port Jefferson railroad station was in need of a face lift. The LIRR embraced the Osborne Plan and renovated the terminal’s stark interior and landscaped its dreary grounds. A sign at the depot celebrated the effort and proclaimed that the modernization of the station would create a “new look” at the “doorway” to the village.

As summer 1967 approached, merchants rushed to dress up their shops by Project Rejuvenation’s rollout on July 4. Along the village’s streets, residents joked they were unable to enter the very stores that were clamoring for customers because their paths were often blocked by the dozens of contractors laboring in Port Jefferson’s commercial center.

With the remodeling finally over, the Chamber reported that about 85% of the village’s shops had renewed their facades. The “unveiling” occurred during the July Fourth Rejuvenation Festival, which featured a parade, soap box derby, fireworks display, and other activities.

Measured by the Chamber’s goal of drawing crowds to Port Jefferson to show off the village’s spruced up shops, the event scored a hit. An estimated 25,000 people visited Port Jefferson during the festival weekend, but aside from its immediate effect, Project Rejuvenation had a lasting impact on the village.

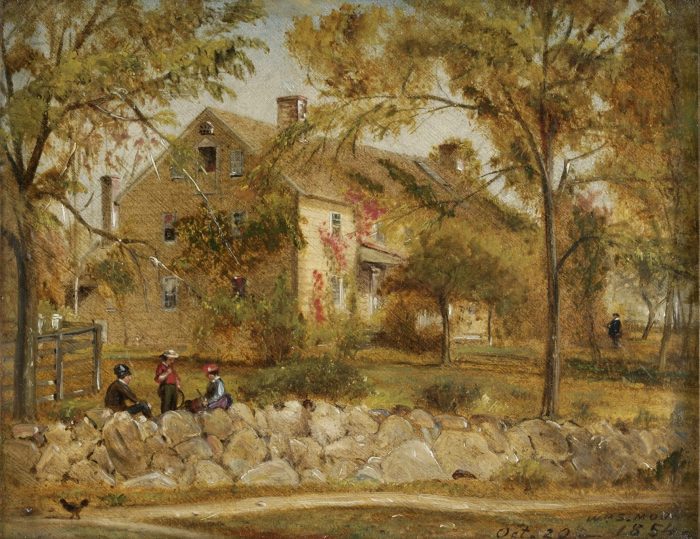

Port Jefferson’s “new look” caught the public eye, put the historic seaport village on the map and sparked Port Jefferson’s commercial renewal by recapturing the tourist market that the village had once enjoyed but had lost to the ravages of time.

Despite this rosy picture, Project Rejuvenation had its detractors. According to critics, the Osborne Plan was to supplement Port Jefferson’s 1965 Master Plan, not became its substitute. Rather than tackling thorny problems that demanded long-range planning, some argued that Port Jefferson went with a short-term solution and kicked the can down the road.

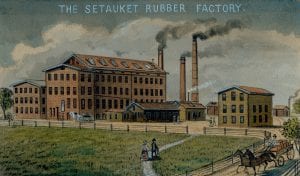

Project Rejuvenation dealt with the village’s shops, not with its waterfront industries. While the Osborne Plan improved Port Jefferson’s storefronts, overburdened trucks still rumbled through the village’s downtown, driving potential customers away.

Although the architecture in Port Jefferson’s business district was eclectic, Project Rejuvenation prescribed an early American style. The results may have been pleasant, but they hardly reflected the village’s history.

Upper Port Jefferson took a back seat during Project Rejuvenation. While the railroad station and some nearby buildings were refaced, most of the work occurred in the village’s downtown. Even the July Fourth Rejuvenation Festival was geared to lower Port Jefferson.

As with any innovation, the Osborne Plan had its drawbacks, but in recognition of its overall success, in 1968 Project Rejuvenation received the Long Island Association’s coveted Community Betterment Award. In addition, Marvey and Lee were honored in 1967 and 1968, respectively, with the Chamber’s prestigious “Man of the Year Award,” given for their outstanding contributions to the community, particularly their roles in Project Rejuvenation.

Over 50 years since the launch of the Osborne Plan, Port Jefferson remains committed to village improvement, continuing the mission of Project Rejuvenation in the revitalization initiatives of today.

Kenneth Brady has served as the Port Jefferson Village Historian and president of the Port Jefferson Conservancy, as well as on the boards of the Suffolk County Historical Society, Greater Port Jefferson Arts Council and Port Jefferson Historical Society. He is a longtime resident of Port Jefferson.

If you can identify any of these players, please reach out to the local history team at Middle Country Public Library at

If you can identify any of these players, please reach out to the local history team at Middle Country Public Library at

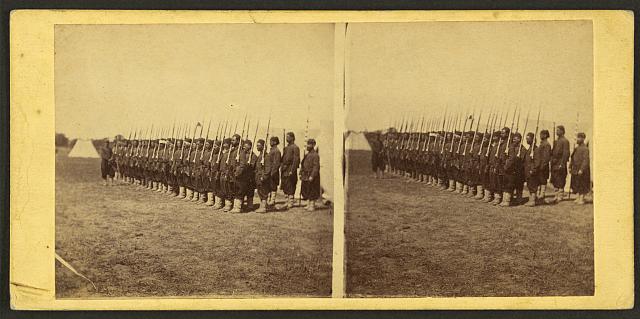

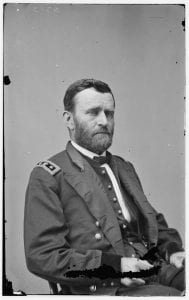

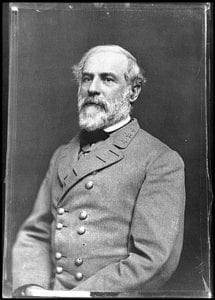

Grant promoted Gen. “Little Phil” Sheridan to run the Army of Shenandoah Valley. For too long, the massive resources of this part of Virginia were used to feed Lee’s forces. Through the tenacity of Sheridan and his men, he carried out the will of Grant who stated that he did not want a “Crow” to fly over these productive lands. Sheridan vehemently fought Confederate Gen. Jubal Early that wreaked havoc on the Union homes and resources that were near Washington, D.C. and Maryland.

Grant promoted Gen. “Little Phil” Sheridan to run the Army of Shenandoah Valley. For too long, the massive resources of this part of Virginia were used to feed Lee’s forces. Through the tenacity of Sheridan and his men, he carried out the will of Grant who stated that he did not want a “Crow” to fly over these productive lands. Sheridan vehemently fought Confederate Gen. Jubal Early that wreaked havoc on the Union homes and resources that were near Washington, D.C. and Maryland. In a matter of days, Lee lost 10,000 soldiers that were killed, wounded and captured. As the union moved forward, the valuable railroads from Petersburg were cut off from Richmond. In a matter of moments, the trenches that were firmly held by the confederates, were empty, and in full retreat. As these two notable southern cities were about to be captured, Lee warned Confederate President Jefferson Davis that Richmond would only be held for a couple of hours and that the government had to flee, or it would be taken by Grant.

In a matter of days, Lee lost 10,000 soldiers that were killed, wounded and captured. As the union moved forward, the valuable railroads from Petersburg were cut off from Richmond. In a matter of moments, the trenches that were firmly held by the confederates, were empty, and in full retreat. As these two notable southern cities were about to be captured, Lee warned Confederate President Jefferson Davis that Richmond would only be held for a couple of hours and that the government had to flee, or it would be taken by Grant.