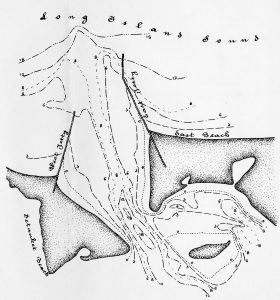

What was happening at the entrance to Port Jefferson Harbor?

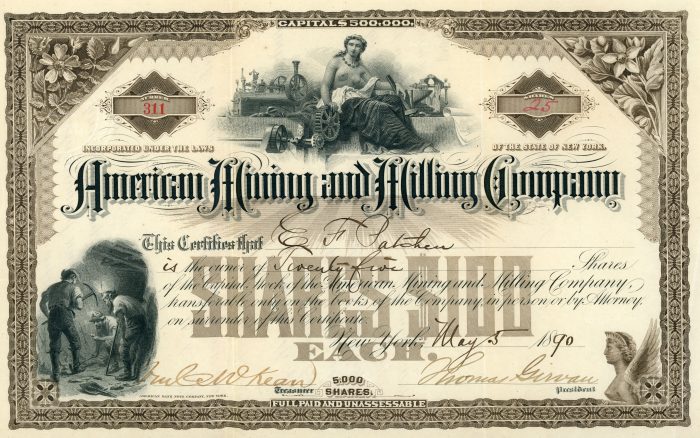

Between 1887-88, the American Mining and Milling Company had built some kind of a plant on the beach adjoining the harbor’s east jetty, but the secretive corporation had not told villagers what it planned to do at the factory.

Located on land in what is now McAllister County Park, the complex included three frame structures containing engines and machines, a track for railcars, stables, a dock and housing for laborers. Pipes brought fresh water to the works from an offsite well.

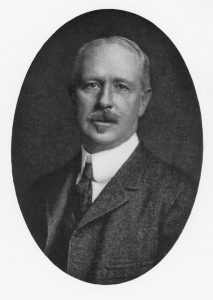

Led by its president, prominent Brooklyn financier and politician Silas B. Dutcher, the AMMC had cobbled together the property by leasing shorefront on the east side of Port Jefferson Harbor from Brookhaven Town and the 1200-acre Oakwood estate from the Strong family.

Thomas Girvan, the superintendent of the plant and Dutcher’s successor as the AMMC’s president, was pressed by Port Jefferson’s residents and local newspapers to reveal the corporation’s intentions, but Girvan was not forthcoming. In addition, the AMMC’s employees were sworn to secrecy and worked behind barricaded doors.

The mystery only fueled wild rumors in Port Jefferson where villagers speculated that the AMMC was digging for Captain Kidd’s treasure, extracting aluminum, manufacturing roofing materials or making fine glass.

The AMMC was actually experimenting with a new method for grinding stone and sand. Seeing enormous profits in the venture, management was guarding the process from potential competitors.

The finished product, as fine as flour, was sold for filtering purposes, while byproducts, such as bird gravel, were marketed as well.

Not enjoying much commercial success, the plant closed in summer 1892, its income insufficient to meet the AMMC’s significant outlay of capital and labor. Lawsuits quickly followed, creditors demanding monies due and employees back wages.

After the works was sold at a sheriff’s sale, limited operations at the plant resumed in Dec. 1892, but attempts at reviving the flagging business were dashed on Sunday, Jan. 15, 1893, when a spectacular fire of undetermined origin destroyed most of the complex.

Without insurance on the plant, the new owners removed what could be salvaged from the ruins of the blaze and closed shop in Port Jefferson.

In the years following the fire, there were reports that some of the former employees at the AMMC’s complex had contracted a fatal lung disease, perhaps brought on by continually inhaling stone dust, marking a deadly end to the plant’s operations in Port Jefferson.

Kenneth Brady has served as the Port Jefferson Village Historian and president of the Port Jefferson Conservancy, as well as on the boards of the Suffolk County Historical Society, Greater Port Jefferson Arts Council and Port Jefferson Historical Society. He is a longtime resident of Port Jefferson