Hometown History: Bygone Port Jefferson lives again — The writings of L. Frank Tooker

There is a rich selection of non-fiction books about Port Jefferson’s early years, but perhaps because they are mostly novels and magazine articles, L. Frank Tooker’s literary works are not often found on Port Jefferson’s local history bookshelf.

This omission is unfortunate since Tooker’s writings transport us back to nineteenth-century Port Jefferson, letting readers feel the village’s past as formal history cannot, making a bygone age live again.

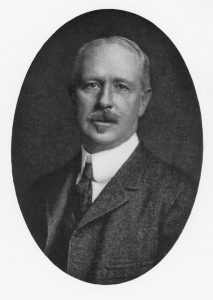

Tooker was born in Port Jefferson on Dec. 18, 1854 and came from a seafaring lot. He was raised in a house at 108 High Street, a short walk from the village’s harbor and shipyards where he spent much of his spare time.

While still a youth, Tooker sailed aboard his family’s ships and traveled to exotic ports, including one memorable voyage during the Civil War to Christiansted on Santa Cruz Island in the West Indies.

After graduating from Yale, Tooker served as the Suffolk County deputy clerk before joining the editorial staff of The Century Magazine where he worked from 1885-1925 and first recognized the talents of “unknown” author Joseph Conrad.

Tooker and his wife Violette (nee Swezey) resided in various communities including Brooklyn and Riverside, Connecticut, but frequently returned to Port Jefferson where they summered with their children, Lewis and Helen.

In Tooker’s first novel, “Under Rocking Skies,” we sail on a brig bound for Santa Cruz Island along with Tom Medbury, the vessel’s mate, and Hetty March, the captain’s daughter, a couple destined to fall in love.

The plot is typical of many romances, but it is the author’s depiction of “Blackwater,” the homeport where the story begins, that holds the reader’s attention.

Tooker peppers his tale with references to Blackwater, a thinly veiled Port Jefferson, with descriptions of its streets, churches, shoreline, cherry trees, shops, and wharves, capturing life during the village’s shipbuilding heyday.

“The Middle Passage,” Tooker’s second novel, recounts the adventures of David Lunt, a native of Blackwater, who sails on a number of ships, one chartered to transport a “cargo” of enslaved Africans to the New World, another to carry arms for South American revolutionaries.

Returning to Blackwater between each of his hair-raising voyages, the high-spirited Lunt woos Lydia Wade, but is prohibited from seeing the young woman because of his wild ways.

After a penitent Lunt publicly acknowledges his reckless behavior, Lydia’s father relents and allows the courtship to continue.

Through Lunt, we also discover there is a dark side of Blackwater, where a two-faced “Captain Joe” pretends to be an upright citizen, but secretly profits from the illegal slave trade, suggesting the complicity of some from Port Jefferson in fitting out the slaver Wanderer in 1858.

Besides historical fiction, Port Jefferson is central again in “A Boyhood Alongshore,” one of the scores of features penned by Tooker and published in The Century Magazine.

In the story, Tooker reminisces about growing up in the 1860s during Port Jefferson’s “cherished past,” a time for him of flying kites, playing marbles, fishing, swimming, boating, and gathering beach plums.

But Tooker is at his best when writing about the “smells of the shipyards,” especially in the article’s excellent account of the launching of the bark Carib at Port Jefferson’s Bayles Shipyard in 1868.

“As long as life lasts,” Tooker concludes the piece, “I shall go to the high, green hill back of our village where lie our dead” and the view over land and water is “always beautiful.”

Seemingly drawn to Port Jefferson’s Cedar Hill Cemetery, Tooker was buried there following his death on Sept. 17, 1925, marking the return of a native son to his beloved village.

Kenneth Brady has served as the Port Jefferson Village Historian and president of the Port Jefferson Conservancy, as well as on the boards of the Suffolk County Historical Society, Greater Port Jefferson Arts Council and Port Jefferson Historical Society. He is a longtime resident of Port Jefferson.