Stress may increase cold virus severity

By David Dunaief, M.D.

September marks the beginning of the academic calendar and noticeably shorter daylight hours. The pace of life tends to become more hectic. Although some stress is valuable to help motivate us and keep our minds sharp, high levels of constant stress can have detrimental effects on the body.

It is very likely that there is a mind-body connection when it comes to stress. In other words, it may start in the mind, but it can lead to acute or chronic disease promotion. Stress can also play a role with your emotions, causing irritability and outbursts of anger and possibly leading to depression and anxiety.

Stress symptoms are hard to distinguish from other disorders, but they can include stiff neck, headaches, stomach upset and difficulty sleeping. Stress may also be associated with cardiovascular disease, with an increased susceptibility to infection from viruses causing the common cold and with cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s (1).

A stress steroid hormone called cortisol is released from the adrenal glands and can have beneficial effects in small bursts. We need cortisol in order to survive. Some of cortisol’s functions include raising glucose (sugar) levels when they are low and helping reduce inflammation and stress levels (2). However, when cortisol gets out of hand, higher chronic levels may cause inflammation, leading to disorders such as cardiovascular disease, as research suggests. Let’s look at the evidence.

A stress steroid hormone called cortisol is released from the adrenal glands and can have beneficial effects in small bursts. We need cortisol in order to survive. Some of cortisol’s functions include raising glucose (sugar) levels when they are low and helping reduce inflammation and stress levels (2). However, when cortisol gets out of hand, higher chronic levels may cause inflammation, leading to disorders such as cardiovascular disease, as research suggests. Let’s look at the evidence.

Inflammation

Inflammation may be a significant contributor to more than 80 percent of chronic diseases, so it should be no surprise that it is an important factor with stress. In a meta-analysis (a group of two observational studies), high levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), a biomarker for inflammation, were associated with increased psychological stress (3).

What is the importance of CRP? It may be related to heart disease and heart attacks. This study involved over 73,000 adults who had their CRP levels tested. The research went further to suggest that increased levels of CRP may result in more stress and also depression. With CRP higher than 3.0 there was a greater than twofold increase in depression risk. The researchers suggest that CRP may heighten stress and depression risk by increasing levels of different proinflammatory cytokines, inflammatory communicators among cells (4).

In another study, results suggested that stress may influence and increase the number of hematopoietic stem cells (those that develop all forms of blood cells), resulting specifically in an increase in inflammatory white blood cells (5). The researchers suggest that this may lead to these white blood cells accumulating in atherosclerotic plaques in the arteries, which ultimately could potentially increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

Chronic stress overactivates the sympathetic nervous system — our “fight or flight” response — which may alter the bone marrow where the stem cells are found. This research is preliminary and needs well-controlled trials to confirm these results.

Infection

Stress may increase the risk of colds and infection. Cortisol over the short term is important to help suppress the symptoms of colds, such as sneezing, cough and fever. These are visible signs of the immune system’s infection-fighting response.

However, the body may become resistant to the effects of cortisol, similar to how a type 2 diabetes patient becomes resistant to insulin. In one study of 296 healthy individuals, participants who had stressful events and were then exposed to viruses had a higher probability of catching a cold. It turns out that these individuals also had resistance to the effects of cortisol. This is important because those who were resistant to cortisol had more cold symptoms and more proinflammatory cytokines (6).

Diabetes and heart disease

When we measure cortisol levels, we tend to test the saliva or the blood. However, these laboratory findings only give one point in time. Thus, when trying to determine if raised cortisol may increase cardiovascular risk, the results are mixed. However, in a study measuring cortisol levels from scalp hair was far more effective (7). The reason for this is that scalp hair grows slowly, and therefore it may contain three months’ worth of cortisol levels. The study showed that those in the highest quartile of cortisol levels were at a three times increased risk of developing diabetes and/or heart disease compared to those in the lowest quartile. This study involved older patients between the ages of 65 and 85.

Lifestyle changes can reduce effects of stress

Lifestyle plays an important role in stress at the cellular level, specifically at the level of the telomere, which determines cell survival. The telomeres are to cells what the plastic tips are to shoelaces; they prevent them from falling apart. The longer the telomere, the slower the cell ages and the longer it survives. In a study, those women who followed a healthy lifestyle — one standard deviation over the average lifestyle — were able to withstand life stressors better since they had longer telomeres (8).

This healthy lifestyle included regular exercise, a healthy diet and a sufficient amount of sleep. On the other hand, the researchers indicated that those who had poor lifestyle habits lost substantially more telomere length than the healthy lifestyle group. The study followed women 50 to 65 years old over a one-year period.

In another study, chronic stress and poor diet (high sugar and high fat) together increased metabolic risks, such as insulin resistance, oxidative stress and central obesity, more than a low-stress group eating a similar diet (9). The high-stress group members were caregivers, specifically those caring for a spouse or parent with dementia. Thus, it is especially important to eat a healthy diet when under stress.

Interestingly, in terms of sleep, the Evolution of Pathways to Insomnia Cohort (EPIC) study shows that those who deal with stressful events directly are more likely to have good sleep quality. Using medication, alcohol or, most surprisingly, distractors to deal with stress all resulted in insomnia after being followed for one year (10). Cognitive intrusions or repeat thoughts about the stressor also resulted in insomnia.

Psychologists and other health care providers sometimes suggest distraction from a stressful event, such as television watching or other activities, according to the researchers. However, this study suggests that this may not help avert chronic insomnia induced by a stressful event. The most important message from this study is that how a person reacts to and deals with stressors may determine whether they suffer from insomnia.

Constant stress is something that needs to be recognized. If it’s not addressed, it can lead to suppressed immune response or increased levels of inflammation. CRP is an example of an inflammatory biomarker that may actually increase stress. In order to address chronic stress and lower CRP, it is important to adopt a healthy lifestyle that includes sleep, exercise and diet modifications. Good lifestyle habits may also be protective against the effects of stress on cell aging.

References: (1) Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2014 Aug. 29. (2) Am J Physiol. 1991;260(6 Part 1):E927-E932. (3) JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:176-184. (4) Chest. 2000;118:503-508. (5) Nat Med. 2014;20:754-758. (6) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:5995-5999. (7) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2078-2083. (8) Mol Psychiatry Online. 2014 July 29. (9) Psychoneuroendocrinol Online. 2014 April 12. (10) Sleep. 2014;37:1199-1208.

Dr. Dunaief is a speaker, author and local lifestyle medicine physician focusing on the integration of medicine, nutrition, fitness and stress management. For further information, visit www.medicalcompassmd.com or consult your personal physician.

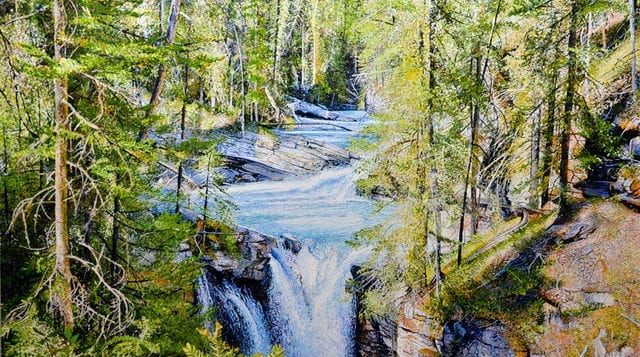

Ross Barbera, a graduate of Pratt Institute, is known for his representational acrylic paintings on canvas, watercolors on paper, original jewelry and digital and abstract art. Presently teaching at St. John’s University in the Art and Design Department in Queens where he was chairman for three years, Ross continues to win many juried awards and prestigious grants to pursue his prolific art career.

Ross Barbera, a graduate of Pratt Institute, is known for his representational acrylic paintings on canvas, watercolors on paper, original jewelry and digital and abstract art. Presently teaching at St. John’s University in the Art and Design Department in Queens where he was chairman for three years, Ross continues to win many juried awards and prestigious grants to pursue his prolific art career.