Book Review: ‘Is Superman Circumcised?’

By Jeffrey Sanzel

There’s no real way to prove this, of course, but the Man of Steel’s image — the muscular body wrapped in skintight primary colors, a cape billowing behind him and a large S splayed across his chest — is universally recognized … From the very young to the very old, from Australia to Algeria to Alaska, it’s a pretty safe bet that almost everyone knows Superman.

— excerpt from Is Superman Circumcised?

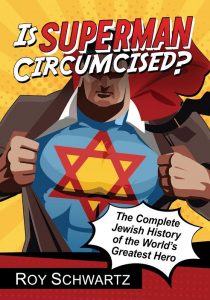

In Is Superman Circumcised? (McFarland Publishing), Roy Schwartz investigates the creators behind the most iconic superhero and his symbolic connection to Judaism and his place in the general cultural pantheon. It is a fascinating work that mines the historical and sociological place of the Man of Steel.

Author Schwartz was born and raised in Tel Aviv and began reading comics at age nine. It was through this medium that he learned English. (Comics allowed him to be comfortable with using the word “swell.”) In his freshman year of college, Schwartz wrote an essay entitled “World’s Finest: Superman and Batman as Didactic Utopian and Dystopian Figures.” Throughout his New York college career, he continued to study the power and place of comic lore, building to his senior thesis, which was the launching source of this book.

Part of Schwartz’s connection to Superman was rooted in their mutual connection of being immigrants, sharing Superman’s sense of alienation, loneliness, and sense of mission. As a result, Schwartz continually surveys the concepts in the Superman oeuvre.

Jewish influence in the comic book industry is easily traced to its roots. The majority of the original writers and artists were children of immigrants. Superman’s creators — writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster — are very much part of this. They “freely borrowed elements from their cultural environment, including the extensive Jewish tradition of heroic stories about men and women given special abilities to defend the helpless, from biblical to rabbinical.”

The book explains in detail how Superman’s origins and adventures reflect the Jewish experience, both biblical and historical, as a prophetic figure and modern hero:

Their Man of Tomorrow reimagined a mythology is old as civilization, capturing the imagination of America and the world. From Krypton’s destruction echoing the biblical flood in Genesis, to his origin as a baby rocketed to safety paralleling that of Moses and Exodus, to the Clark Kent persona as a metaphor for Jewish immigrant assimilation, to Kryptonite symbolizing remnants of the Jewish civilization destroyed by the Holocaust, to this role as a modern Golem advocating the New Deal, open immigration and intervention in World War II, Superman’s legend is consistent as Jewish allegory.

Schwartz gives a detailed account of Siegel and Shuster’s upbringing, inspirations, and odyssey. He traces them from their teen years, when they conceived of the hero, their attempts to sell it, their breakthrough and rise, and ultimately, both its loss and legacy. On March 1, 1938, they sold the first Superman story to DC for $10 a page, totaling $130. Unfortunately, the contract cost them millions of dollars as they sold the story and the rights to the character as well. This would haunt them for the rest of their lives. Moreover, the impact of this sale would continue beyond their deaths, entangling issues of ownership that the estates would wage.

The earliest part of the book focuses on the biblical connections. Superman is most closely associated with Moses and Samson, but Schwartz also explores Superman as a Jesus figure. While the early Superman reflects an Old Testament figure, in film, television, and later incarnations, the Christ symbolism became strongest.

The earliest part of the book focuses on the biblical connections. Superman is most closely associated with Moses and Samson, but Schwartz also explores Superman as a Jesus figure. While the early Superman reflects an Old Testament figure, in film, television, and later incarnations, the Christ symbolism became strongest.

In the second section of the book, Schwartz expands to the general world of comic books and the influence of the exodus of Eastern European Jewry to the lower East Side of Manhattan. He traces the history of comic books, noting that it was at the bottom of the artistic industry, but one in which Jews could participate, having been blocked out of legitimate magazines and newspapers.

He discusses both the religious and secular influences on this particular art and its manifestations in various titles. There is an emphasis on the bridging of the foreign culture integrating into American life. “Whatever his metaphorical foundation, the Man of Tomorrow is, and was always intended to be, a symbol of cultural collaboration, exemplified by his origin story as an alien refugee taken in by loving Americans and his life’s mission of bringing to bear the gifts of his heritage for the benefit of all.”

There is no question that the rise of anti-Semitism at home (the KKK and the Bund) and abroad (the ascent of the Nazis) strongly influenced the comic. Amid this rise in anti-Jewish sentiment, Action Comics #1 debuted Superman in June 1938. A year later, Superman #1 appeared, which coincided with the St. Louis — known as “the Voyage of the Damned” — being refused entry and sent back to Germany. Thus, Superman’s origin of a “refugee from a destroyed home when traveling to safe harbor in a vessel granted asylum by kindly Americans” could not have been more germane.

Schwartz gives both context and perspective. He points out that the idea of Superman was so original, there was no true point of reference. “How utterly ridiculous Superman must have seemed to editors then. A strongman from outer space, dressed in long johns, wellingtons and a cape. What a mashugana idea.”

Schwartz demonstrates extraordinary insight in his overview of the intersection of comics, the history of heroes and heroines, theological knowledge, and pop culture. He easily communicates how time and place and the personal history of the creators manifested in the character’s launch. Schwartz imparts the information with humor, focus, a range of examples, and an uncanny ability to join the concepts in an accessible, entertaining, and enlightening way. He easily debunks esoteric theories and interpretations that are rooted in extreme scholarship but have no factual basis. He draws on a wide range of sources, including Siegel’s unpublished memoir.

Schwartz addresses Superman as the ultimate wish-fulfillment: “He’s neurotic catharsis in a cape.” He spends time dissecting the question of who Superman’s true self: the caped hero or Clark Kent. Schwartz delves into the philosophical and cultural aspects, touching on everything from Nietzsche and religion to the accusation of comic books as a corrupting influence. He discusses the many incarnations and traces the constant reinvention of Superman in print and celluloid. He notes the contradiction both the liberal and conservative claim on Superman.

In all of this, the final takeaway, and perhaps the heart of this exploration, is one of identity. The message is a powerful one and valuable as much now as it was in 1938. “For all their glory and symbolism of American might and rectitude, superheroes were created by a band of Jewish kids from the ghetto, and they reflected their fears, fantasies and faith — if not religious, then in the promise of the nation that took them or their parents in.” Superman, as an immigrant, “showed the refugees weren’t, and some insisted, dangerous strangers from the hinterlands, ungrateful, clannish and treacherous. They were thankful and faithful contributors to the American collective.”

Is Superman Circumcised?: The Complete Jewish History of the World’s Greatest Hero is available online at www.amazon.com and www.barnesandnoble.com. Visit the author’s website at www.royschwartz.com.