By Daniel Dunaief

Combining forces to form a three-part team, they strive to understand processes that are as visually stunning and inspirational as they are complex and elusive.

Clouds, which are so important to weather and climate, are challenging to understand and predict, as numerous processes affect properties at a range of scales.

A team from Brookhaven National Laboratory has provided the atmospheric sciences community with a host of information that advances an understanding of clouds.

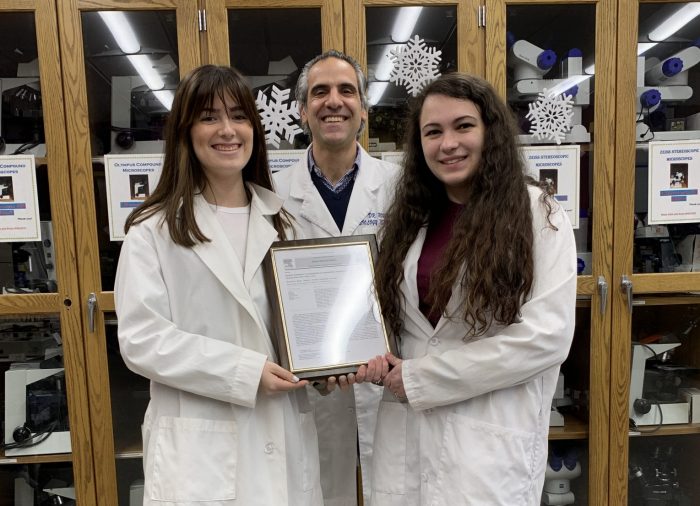

In the atmospheric sciences community, “we typically talk about the three legs of a stool: modeling/ theory; field measurements; and targeted laboratory studies,” explained Arthur Sedlacek, Chemist in the Environmental and Climate Science Department.

Sedlacek conducts field experiments by collecting air samples from clouds in a range of locations such as flying through wildfire plumes.

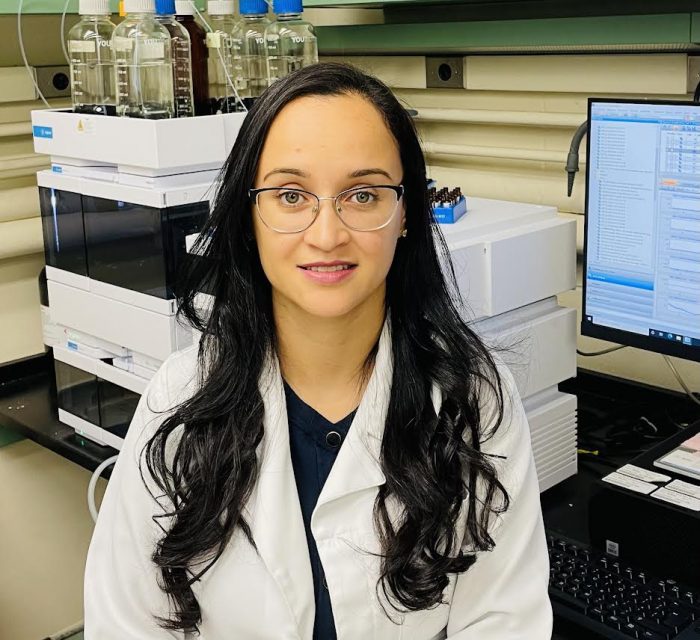

In the beginning of 2021, BNL added postdoctoral researcher Ogochukwu Enekwizu to bolster another leg of that stool. Enekwizu conducts the kind of laboratory studies that provide important feedback and data for the work of Sedlacek and cloud modelers like Nicole Riemer, Professor in the Department of Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Illinois-Urbana Champaign.

Enekwizu studies how soot aerosols from wildfires influence the lifetime and formation of clouds. She’s also investigating how soot-cloud interactions affect the absorption and scattering of light by soot particles.

Wildfires provide kindling for the climate, as fires release warming agents that contribute to increases in global temperatures which result in more wildfires. By determining how these smaller scale processes in soot affect clouds, Enekwizu can reduce the so-called error bars or level of uncertainty in the models other scientists create and that rely on the data she develops.

Enekwizu’s collaborators appreciate her contribution. As a modeler, Riemer suggested that Enekwizu’s work provided key information.

“While the microscale processes of soot restructure are incredibly complicated, [Enekwizu] was able to boil it down to a few simple parameters,” Riemer explained. “This makes it feasible to implement this process in a model like ours, which look at aerosol populations, not just a few individual particles. From there, we can come up with ways to implement this knowledge into climate models, which are still much more simplified than the model that we are developing.”

Sedlacek, who is her supervisor, suggested that Enekwizu’s work is “now on the cusp of answering important questions of how aerosols interact with clouds.” He descried her set up as “truly unique” and expects her results to inform the community about wildfire aerosol-cloud interactions and will offer guidance on other necessary field measurements.

In broader research terms, wildfires can be important for the ecosystem, as they remove decaying material, clear out underbrush, release nutrients back into the soil and aid the germination of seedlings

The increasing frequency, duration and intensity of these fires has been important to the scientific community. The general public has become increasingly aware of its importance as well, Enekwizu said.

Collaborations

Recruited to BNL by Sedlacek and Atmospheric Scientist Ernie Lewis, Enekwizu is considering collaborations with other researchers at BNL.

She has started speaking with scientists at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials about exploring soot microstructure in a planned joint collaboration with her New Jersey Institute of Technology PhD advisor Dr. Alexie Khakizov. For this effort, Enekwizu has been in discussions with Dmitri Zakharov, who is in charge of the environmental transmission electron microscope at the CFN.

She hopes to take samples and introduces forces under a controlled environment in the transmission electron microscope to see how that affects the structure of soot in fine detail.

Looking at the news with one wildfire event after another, Enekwizu feels compelled to conduct research in the lab and share data amid “a heightened sense of urgency to get this work done” and to share it with the world at large.

Scientific origins

Born in the southeastern part of Nigeria in Enugu and raised in Enugu, Lagos and Abuja, Enekwizu developed an interest in science at 13. She enjoyed classes in a range of sciences and said chemistry was her favorite.

“I knew I was not going to go into medicine because I was squeamish,” she said.

Chemical engineering fascinated her and also appeared to offer career opportunities.

During a chemical engineering internship, she worked at the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation where she learned about flaring practices. It inspired her final year project on biogas as a renewable energy source and sparked her curiosity on the fate of pollutants and particulate matter that arise from legal and illegal flaring activities.

In flaring, companies burn off excess gas to control pressure variations, increasing the safety of the operation at the expense of burning a potential resource.

When Enekwizu was at NJIT, Lewis, who is a longtime collaborator with Sedlacek, reached out to Khakizov to inquire about someone with a background in carbonaceous aerosols. After interviewing with Lewis, Sedlacek and others, Enekwizu received the job offer and began working in January of 2021.

A resident of Ridge, Enekwizu, who goes by the name “Ogo,” enjoys festivals and events around Long Island. She also appreciates the area’s ubiquitous beaches and has delighted in strawberry picking.

She hopes to explore Montauk later this spring or summer.

Mentoring

Enekwizu is passionate about mentoring students, particularly those who might be under represented in the field of Science, Technology, Engineering and Medicine.

She served as a graduate student mentor for Divyjot Singh, who was an undergrad at NJIT. Enekwizu taught Singh, who had grown up in Bhopal, India and had only been in the United States for six months when they met, “how to come up with research questions, how to develop hypotheses, how to write a proposal, how to make good presentations for conferences and everything in between,” he explained in an email.

While working with her, Singh found his passion for research and decided to pursue a PhD.

Enekwizu is also passionate about supporting young women in science. She suggested that young black girls sometimes feel intimidated by STEM classes and careers. She urges a hands on approach to teaching and hopes to be a role model.

“If young girls see people like me thrive in STEM, they’ll be encouraged not to give up,” she said. “That is a huge win, in my opinion.”