Breaking news from the Richard Leakey Memorial Conference

By Daniel Dunaief

A species of archaic humans is defying conventional wisdom about what it means to be human.

Homo naledi, which were discovered in a cave about 25 miles away from Johannesburg, South Africa, had brains that were about a third the size of ours. That, previous research suggested, likely limited their ability to engage in a range of activities, like burying their dead or creating symbols.

Wrong and wrong.

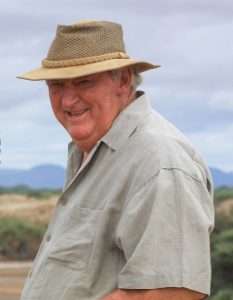

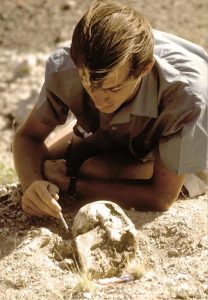

In an expedition through narrow caves that required him to lose 55 pounds just to get to the site, Lee Berger, National Geographic Explorer in Residence and Lead of the Rising Star program, along with a team of other scientists, studied the remains of these humans that lived over 236,000 years ago. The bones they studied and, in some cases excavated, were buried deep in the Rising Star Cave.

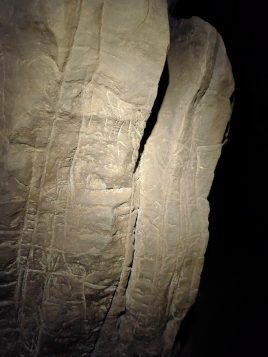

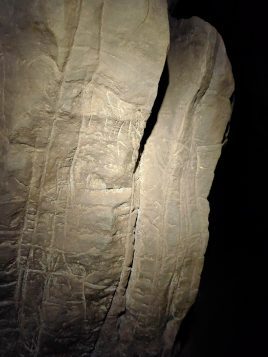

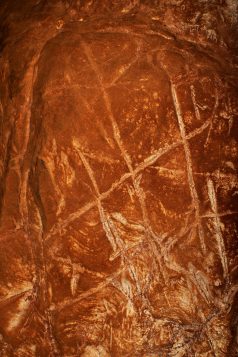

Along the wall of a cave, the researchers also found symbols, including crossed lines and swirls.

“Big brains don’t explain what we thought they explain,” Agustín Fuentes, Professor of Anthropology at Princeton University and National Geographic Explorer and On-Site Biocultural Specialist, said during a press briefing announcing the discoveries. This research “takes humans off the pedestal.”

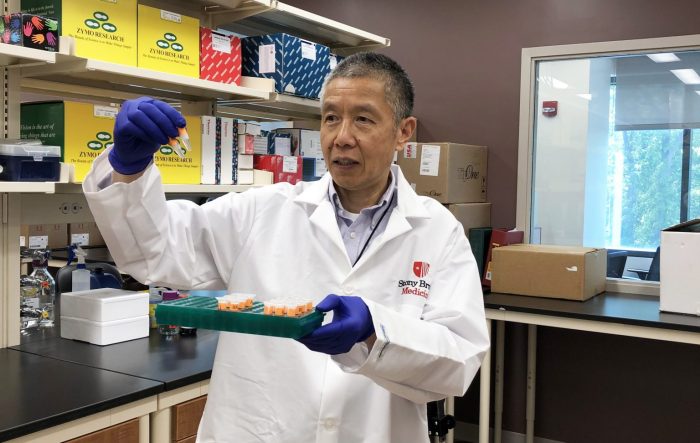

The research, which was shared at the Richard Leakey Memorial Conference at Stony Brook University on June 5, is published in the journal eLife.

Berger wanted to share his latest findings with the conference, particularly given the important role Leakey played in his career.

Berger had known Leakey for 34 years. When they met, Leakey, who was his “idol,” directed Berger to follow his dream of searching for fossils in South Africa. Leakey and Berger remained close throughout the decades.

“I owe him my entry into this field,” said Berger.

Indeed, Berger feels that Leakey was, “in some ways, responsible for the discovery” about the burials and cave drawings of Homo naledi. “I’m very personally indebted” to Leakey.

Extraordinary effort

While scientists don’t know what the lines in the dolomitic limestone walls signified, they believe Homo naledi, whose name in Sotho language means “star,” made those marks.

Natural processes over the course of over 200,000 years wouldn’t have left such a distinctive pattern. In addition, the depth of the markings, which would have taken considerable effort and a tool to create, indicate a concerted and sustained physical effort.

The dolomite is about half as hard as a diamond, which would have taken an “extreme amount” of work, Berger said. Several of the lines suggest multiple efforts to make carvings. “These are engravings that are not done in one sitting,” he said.

During the press briefing, Berger indicated that other species of early humans didn’t leave any evidence of entering the same cave. “There’s no evidence of humans” other than the scientists who published the paper “that entered the cave,” he said.

At this point, researchers, who are trying to minimize any disturbance in the cave, haven’t pinpointed an exact date for the symbols.

“In time, we’ll likely be able to date” the symbols, said Berger. The researchers arrived at the approximate date and linked the symbols to Homo naledi through association and context, he explained.

Homo naledi are the only humans who left any evidence of their presence in the cave.

Researchers described the arduous process of descending through narrow passageways to arrive at the burial site, which Berger discovered in 2013.

The site is extraordinarily difficult for modern humans to navigate. In addition to losing weight to get through small openings, Berger tore his rotator cuff climbing out of the site last July. He is still recovering, but said losing weight and even sustaining an injury was worth the effort.

While modern scientists use headlamps and battery-powered lights to record their discoveries, earlier humans would have had to carry some form of portable fire with them to bring their dead to their burial sites and to make carvings in the walls.

“How they’re making that fire and the exact mechanism of transport, I think, will be established over the next several years as we study all the occurrences of it,” Berger said.

“For us to say something clearly, definitely, strongly, again as [Berger] has said, we need to go back and excavate some more and check out more areas that we might have missed because clearly we walked straight past this,” said Keneiloe Molopyane, National Geographic Explorer and Lead Excavator of Dragon’s Back Expedition.

New perspectives

As far as a DNA analysis, the team hasn’t yet found anything they can test in the fossils. They are planning to test the sediment.

The researchers have left large amounts of evidence in place, which includes multiple other burials that haven’t been excavated. Berger suggested that the images and information from this site “provide as robust evidence for burial and graves as for practically any grave ever published for humans or otherwise.” Researchers examining this information will realize that “more works needs to be done.” As for what that entails, one of the plans is to bring additional technology and specialists into the area.

Homo naledi “intensely altered this space across kilometers of underground cave systems, and I think that deserves not just the involvement of our team, but the involvement of every scientist around the world who can participate, and perhaps technologists and other people who have ideas about how/ what we do,” Berger added.

As for the implications of this research, the scientists suggested that the discovery and the analysis will continue to alter the perspectives of researchers and students of human history.

“All of us who write textbooks or major articles about this probably have to go back and shift what we said about big brains, meaning, complex meaning-making behavior, or the kind of complex experiences of grief, social community, that’s associated with mortuary and funerary practices,” Fuentes said. “It makes us think about human evolution really in a new way, and puts us back closer to a starting point, and showing again that we know a lot less than we thought we did.”

The University, which has 15 speakers among the 40 scientists delivering lectures, will celebrate the achievements of famed and late scientist and conservationist Richard Leakey and will bring together researchers from all over the world to celebrate the research in Africa that has revealed important information about early human history.

The University, which has 15 speakers among the 40 scientists delivering lectures, will celebrate the achievements of famed and late scientist and conservationist Richard Leakey and will bring together researchers from all over the world to celebrate the research in Africa that has revealed important information about early human history.