By Daniel Dunaief

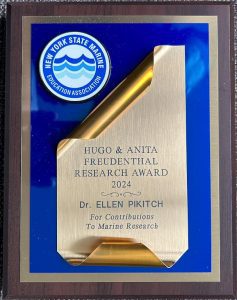

Five decades after graduating from John Dewey High School in Coney Island, Ellen Pikitch recently received an award from a group founded by one of her high school teachers.

Lou Siegel, one of the founders and Nassau County Director of the New York State Marine Education Association (NYSMEA), helped present the Hugo and Anita Freudenthal Award for contributions to furthering scientists’ understanding of the marine environment to his former student by zoom on April 20th.

“It’s wonderful when you have students that follow the same interests that you’ve had,” said Siegel. “Not only has she done excellent work in the field, but she worked to popularize it and to get it out to the general public.”

Endowed Professor of Ocean Conservation Science in the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University, Pikitch, who grew up in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, a short train ride from the New York Aquarium, and who said she knew she wanted to be a marine biologist “from the time I was born,” has tackled marine conservation issues from several perspectives.

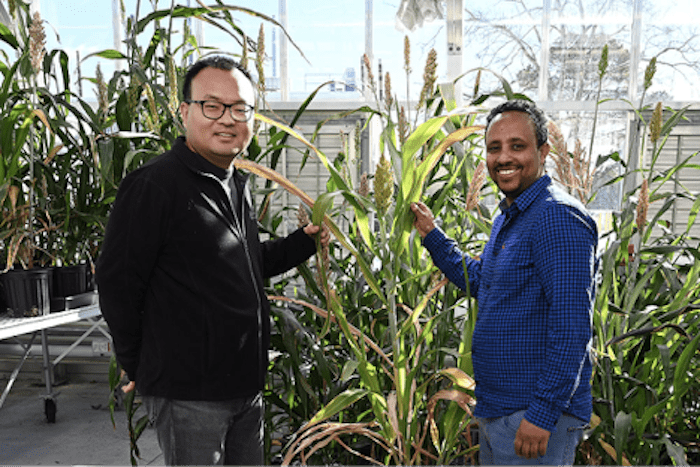

Pikitch, Distinguished Professor Christopher Gobler and Associate Professor Bradley Peterson worked to restore Shinnecock Bay by planting filter feeders such as hard clams and oysters and reseeding seagrass beds, which have cleaned the waters and prevented the appearance of brown tides. For at least five years, Shinnecock Bay hasn’t had any brown tides, breaking a decades-long cycle.

Indeed, Mission Blue named Shinnecock Bay, which is home to a range of biodiversity including dolphins, a wide variety of fish and birds and, occasionally, sharks, as the first Hope Spot in the state of New York. Other Hope Spots include global attractions such as The Galapagos Islands, the Sargasso Sea and the Ross Sea in Antarctica.

At the same time, Pikitch has been involved in numerous efforts on a global scale to conserve ocean regions through Marine Protected Areas. Working with a group of 42 scientists, she helped develop a framework to understand, plan, establish, evaluate and monitor marine protected areas.

Pikitch is following in the footsteps of the Freudenthals for whom the award and recognition is named, as the married couple were involved in a range of local, national and global projects.

Hugo Freudenthal was “the first person to recognize the symbiotic relationship between algae and corals,” said Pikitch. He was also involved in the creation of the first space toilet, designed in the 1970’s for the Skylab, which was America’s first space station and the first crewed research lab in space.

In an amusing presentation called “Turds in Space” at the Experimental Aircraft Association three years ago that is available online at Turds In Space by Hugo D Freudenthal, PhD, Freudenthal explained how he helped design a toilet that would work in zero gravity, which, he said, “was one of the few things on Skylab that worked perfectly.”

The toilet had a soft seat, which was like a saddle, that was lined with holes on the outside and had vectored air coming in from the sides, which brought the feces down into a collection device, the late Hugo Freudenthal described in the video.

Anita Freudenthal, meanwhile, was the first female marine biologist in Nassau County. She also taught and did research at C.W. Post.

“Both of them were accomplished,” said Pikitch. “I’m excited and honored to have received [the award].”

Humble origins

The granddaughter of immigrants who didn’t speak English, Pikitch came from humble origins, as her parents had high school educations.

Pikitch volunteered at the New York Aquarium during high school, where her job was to stand in front of the shark tank and talk about sand tiger sharks.

Living near the aquarium, which is on the beach in Coney Island, strengthened her interest in marine biology. During summer in her childhood, Pikitch and her family took day trips near and in the water, which cultivated her love of the ocean.

Despite her passion for marine biology, Pikitch came from limited means. She credits her high school teachers, including Siegel and math teacher David Hankin for directing her to pursue degrees in higher education.

Ongoing work

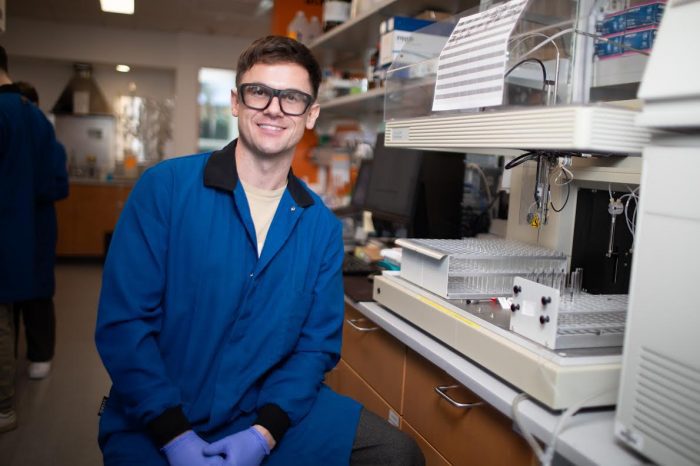

For five years, Pikitch has been using eDNA to study biodiversity in various aquatic habitats.

With eDNA, scientists take environmental DNA from water samples that contain the genetic material shed from scales, fins, tissues, secretions and oils of the organisms living in the water. The genetic material generally lasts about 12 to 24 hours in shallow, warm water.

Environmental DNA has numerous benefits, including that it doesn’t disrupt the ecosystem by removing or harming individuals and it collects DNA from fish and other aquatic organisms that might otherwise be too small, too large or too quick for a trawling net to capture them.

Through an eDNA sample, Pikitch was surprised to find DNA from a basking shark, which is the second largest living shark after the whale shark.

She and other scientists saw a picture in a local newspaper of a basking shark soon after the eDNA sample revealed its presence.

To be sure, an eDNA sample, could, theoretically, include DNA from species outside the range of a sampled environment. Pikitch uses multiple survey methods besides eDNA.

Indeed, she plans to submit a few manuscripts that are in the works later this year that will compare the range of biodiversity from eDNA samples with the species collected from trawling.

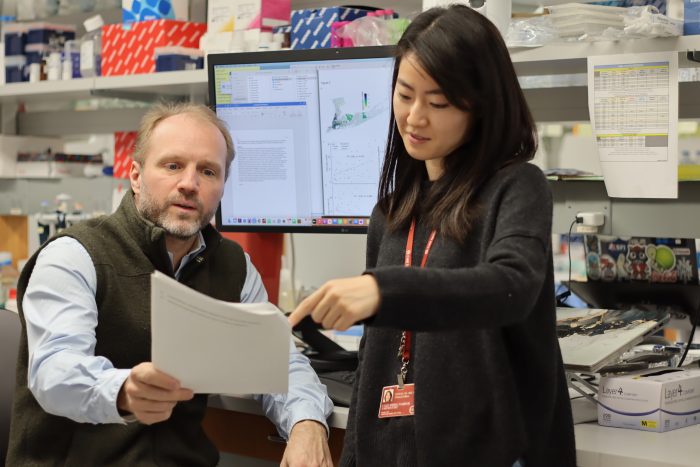

This fall, she’s planning to use high tech equipment that has never been used together before, deploying an uncrewed surface vehicle (or USV) to collect and analyze samples.

Powered by solar energy, the USV doesn’t emit any greenhouse gases and is self-righting, which means that a hurricane could knock it over and, like a Weebles Wobble, it would adjust back to a vertical position in the water.

Pikitch hopes to collect samples off the waters of the Shinnecock Nation. She is involved in consultations with the Shinnecock Nation and is optimistic about a fall collaboration.

Pikitch hopes the eDNA sensor expedition will provide a proof of concept that will encourage other scientists to bring this technology out to remote areas of the ocean, which could help address questions of where to create and monitor the biodiversity of other marine protected areas.

As for the award, Siegel, who helped found the NYSMEA in the same year Pikitch graduated from high school 50 years ago, understands the excitement of the student-teacher connection from the student side as well. Anita and Hugo Freudenthal were his professors at C.W. Post when he earned a master’s in Marine Science.

“It’s like a family tree,” Siegel explained.