By Erin Dueñas

Arleen Buckley ticked off the places she and husband Tom had traveled to before he fell ill. The Port Jefferson couple had visited Italy, Ireland and even China, but a planned trip to Belgium last year had to be canceled after Tom’s battle with polycystic kidney disease — a hereditary condition where cysts develop on the kidneys, leading to the organ’s failure — kept him from traveling.

“He was just too sick,” his wife said. “We were lucky we could get him to the corner.”

Tom Buckley spent months undergoing dialysis three days a week, but the treatments left him weak.

“He wasn’t having a good reaction to the dialysis,” Arleen Buckley said. “I told him we can’t live life like this. It was a tough time.”

Arleen Buckley said she couldn’t bear seeing her husband of 43 years so ill. She suggested giving him one of her kidneys to resolve his health issue but he refused.

“He felt guilty. He didn’t want me putting my life at risk,” she said. “I told him I wanted to live a nice long life — but with him.”

It took months but she eventually convinced her husband to take her kidney, and in September of last year, the couple underwent the surgeries.

Arleen Buckley was up and about just three days later, and while her husband’s recovery took much longer — about six months — he said he feels great. They’re even planning a trip to Scandinavia.

“I couldn’t go anywhere, not even to the movies,” Tom Buckley said. “Now that I’m better I can do whatever I want.”

Last Thursday, April 2, the couple attended the Living Donor Award Ceremony at Stony Brook University Hospital, which honored Arleen Buckley and about 200 other kidney donors. Sponsored by the hospital’s Department of Transplant, kidney recipients presented their living donors with a state medal of honor for the second chance at life.

The ceremony’s keynote speaker was Chris Melz of Huntington Station, who donated a kidney in 2009 to his childhood friend Will Burton, who suffered from end-stage renal failure. The surgeries were successful, and Melz now works with the National Kidney Foundation raising awareness for living donors.

“I want to spark the drive for people to do good,” he said. “Giving is a beautiful thing.”

Arleen Buckley said she was happy to give a kidney to her husband, whom she has known for 50 years.

“I told him, ‘When I was 14 years old, I gave you my heart. At 64, I gave you my kidney,’” the wife said.

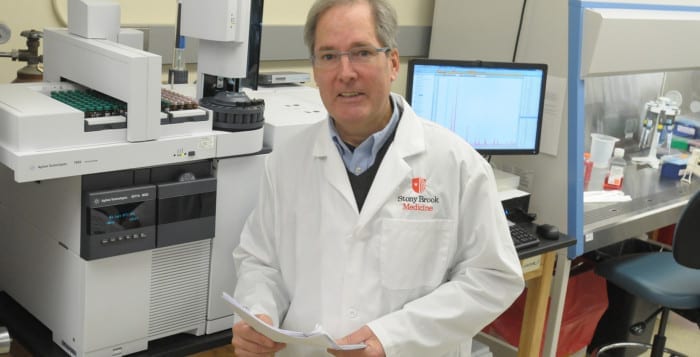

Dr. Wayne Waltzer, director of kidney transplantation services and chair of the Department of Urology at Stony Brook University School of Medicine, called kidney transplants a “new lease on life” for patients who are on dialysis.

“Transplants restore them,” Waltzer said. “They get back the same sense of well-being they had before they got sick.”

According to the National Kidney Foundation, 118,000 Americans are on a waiting list for an organ — 96,000 of those wait for a kidney. Roughly 13 people die daily waiting for the organ, the group said.

Stephen Knapik, Stony Brook University’s living donor coordinator, said that every 10 minutes someone in need of a kidney is added to that list. He called it an honor to work with donors who keep the list from growing.

“I’ve never been in a room with so many superheroes in my life,” Knapik said. “The greatest gift you can give isn’t a boat or a car, it’s the gift of life.”

Waltzer said that donating a kidney involves meeting certain criteria including compatible blood groups and matching body tissues between donor and recipient, as well as ensuring that the recipient has no antibodies that will work against the transplanted organ.

While he said the surgery is sophisticated, he called the science and medicine an incredible achievement.

“The immunosuppressive therapy is so good and the medication so effective that you can override any mismatches,” he said.

This allows for donors to give to loved ones that are not related by blood.

With the most active renal transplant program on Long Island, Stony Brook has done 1,500 transplants since 1981. Waltzer said that donors are doing an “amazing service,” not just to their recipient but also to one of the thousands of people who are on the waiting list for a kidney.

“There is a shortage of organs,” he said. “By donating, you are giving a chance to someone else on that waiting list.”