By Daniel Dunaief

It’s everywhere, from holding the water we drink to providing a cover over the Norman Rockwell painting of “The Three Umpires” to offering a translucent barrier between our frigid winter backyards and the warm living room.

While we can hold it in our hands and readily see through it, glass and its manufacture, which has been ongoing for about 4,000 years, has numerous mysteries.

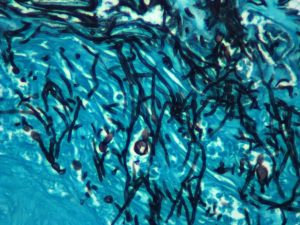

Indeed, given enough temperature and time, glass crystallizes. Controlling the process has been used to increase strength and chemical durability, tailor thermal properties and more over the last several decades.

Evan Musterman, who studied the way lasers served as a localized heat source to induce single crystal formation in glass when he was a graduate student at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania-based Lehigh University, joined Brookhaven National Laboratory in September as a postdoctoral researcher.

Musterman, who received funding for nine months at the end of his PhD program through the Department of Energy’s Office of Science Graduate Student Research program when he was at Lehigh that enabled him to work at BNL, is adding scanning x-ray diffraction mapping as a more user-ready technique at the Submicron Resolution X-ray Spectroscopy beamline (or SRX) that he used as a graduate student.

The beamline looks at x-ray fluorescence measurements, which provide information about the elemental distribution and chemical information, such as oxidation state and bond distances, in an experimental sample. The next component scientists are looking for is using diffraction to inform the crystal structure of the material and to gather information about strain, explained Andrew Kiss, the lead beamline scientist for the SRX.

Musterman hopes to build on the electron diffraction mapping he did during his PhD work when he studied the crystals he laser-fabricated in glass. X-rays, he explained, are more sensitive to atomic arrangements than electrons and are better at mapping strain.

Musterman’s “background in materials science and crystal structures made him an excellent candidate for a post-doc position,” Kiss said.

The SRX has applications in material science, geological science and biological imaging, among other disciplines.

Glass questions

For his PhD research, Musterman worked to understand how glass is crystallizing, particularly as he applied a laser during the process. He explored how crystal growth in glass is unique compared with other methods, leading to new structures where the crystal lattice can rotate as it grows.

Musterman finds the crystallization of glass ‘fascinating.” Using diffraction, he was able to watch the dynamics of the earliest stages after a crystal has formed. In his PhD work, he used a spectroscopy method to understand the dynamics of glass structure before the crystal had formed.

Musterman started working at the SRX beamline in June of 2022. He was already familiar with the beamline operation, data collection and types of data he could acquire, which has given him a head start in terms of understanding the possibilities and limitations.

In his postdoctoral research, he is developing diffraction mapping and is also finishing up the experiments he conducted during his PhD.

Himanshu Jain, Musterman’s PhD advisor at Lehigh who is Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, was pleased with the work Musterman did during his five years in his lab. Jain sees potential future extensions and applications of those efforts.

Musterman’s research “forms a foundation for integrated photonics, which is expected to revolutionize communications, sensors, computation and other technologies the way integrated circuits and microelectronics did 50-60 years ago,” Jain explained in an email. The goal is to “construct optical circuits of single crystal waveguides in a glass platform.”

Musterman’s work “showed details of these optical elements made in glass by a laser,” he added.

Jain, who is an alumnus of BNL, indicated that his lab is continuing to pursue the research Musterman started, with his former graduate student as a collaborator and guide.

Musterman appreciates the opportunity to work with other scientists from different academic and geographic backgrounds. In addition to working with other scientists and helping to refine the functionality of the SRX beamline, he plans to continue glass and glass crystallization research and their interactions with lasers. As he refines techniques, he hopes to answer questions such as measuring strain.

As glass is heated, atoms form an ordered crystalline arrangement that begins to grow. The nucleation event and crystal growth occurs at the atomic scale, which makes it difficult to observe experimentally. Nucleation is also rare enough to make it difficult to simulate.

Most theories describe crystal nucleation and growth in aggregate, leaving several questions unanswered about these processes on single crystals, Musterman explained.

As they are for most material processing, temperature and time are the most important factors for glass formation and glass crystallization.

Historically, studies of glass structure started shortly after the discovery of x-ray diffraction in 1913. In the 1950’s, S. Donald Stookey at Corning discovered he could crystallize glass materials to improve properties such as fracture resistance, which led to a new field of studies. Laser induced single crystal formation is one of the more recent developments.

Musterman and his colleagues found that laser crystallization does not always produce the same phase as bulk crystallization, although this is an active area of research.

Musterman created videos of the earliest stages of crystal growth under laser irradiation by direct imaging and with electron and x-ray diffraction.

Kiss anticipates that Musterman, who is reporting to him, will build infrastructure and understanding of the detection system in the first year, which includes building scanning routines to ensure that they know how to collect and interpret the data.

Once Musterman demonstrates this proficiency, the beamline scientists believe this expanded technical ability will interest scientists in several fields, such as materials science, energy science, Earth and environmental science and art conservation.

Pitching in with former colleagues

While Musterman is not required to work with other beamline users, he has helped some of his former colleagues at Lehigh as they “try to get their best data,” he said. He has also spoken with a scientist at Stony Brook University who has been collecting diffraction data.

A native of Troy, Missouri, Musterman lives in an apartment in Coram. When he was younger, he said science appealed to him because he was “always curious about how things worked.” He said he frequently pestered his parents with questions.

His father John, who owns a metal fabrication and machining business, would take various ingredients from the kitchen and encourage his son to mix them to see what happened.

As for the future, Musterman would like to work longer term in a lab like Brookhaven National Laboratory or in industrial research.