By Daniel Dunaief

It’s a low-tech setting with high stakes. Scientists present their findings, often without slides and pictures, to future colleagues and collaborators in a chalk talk, hoping faculty at other institutions see the potential benefit of offering them an employment opportunity.

For Tobias Janowitz, this discussion convinced him that Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory was worth uprooting his wife and three young children from across the Atlantic Ocean to join.

Chalk talks in most places encourage people to “defend their thinking. Here, it was completely different. They moved on from my chalk talk quickly,” said Janowitz in a recent interview.

Janowitz recalled how CSHL CEO Bruce Stillman asked him “what else will you do that’s important and high risk. He moved me on from that discussion within five minutes and essentially skipped a step I’d usually spend at another institution. It’s a very special place.”

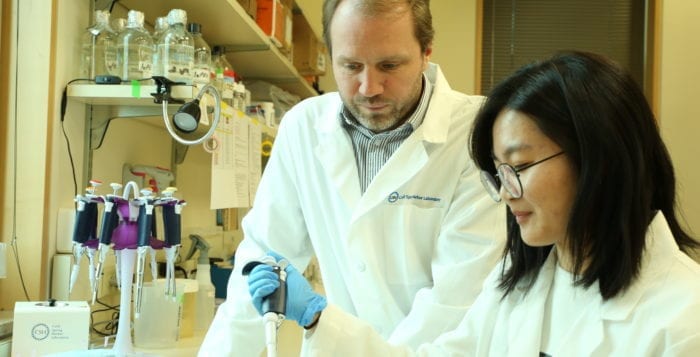

Janowitz, who earned a medical degree and a doctorate from the University of Cambridge, came to the lab to work in a field where he’s distinguished himself with cancer research that points to the role of a glycoprotein called interleukin 6, or IL-6, in a specific step in the progression of the disease, and as a medical oncologist. He will work as a clinician scientist, dedicated to research and discovery and advancing clinical care, rather than delivering standard care.

As CSHL continues to develop its ongoing relationship with Northwell Health, Janowitz said he expects to be “one of the intellectual bridges between the two institutions.”

In his research, the scientist specializes in understanding the reciprocal interaction between a tumor and the body. Rather than focusing on one type of cancer, he explores the insidious steps that affect an organ or system and then wants to understand the progression of signals and interactions that lead to conditions like cachexia, in which a person with cancer loses weight and his or her appetite declines, depriving the body of necessary nutrition.

CSHL Cancer Center Director David Tuveson appreciates Janowitz’s approach to cancer.

“Few scientists are ready to embrace the macro scale of cancer, the multiple organ systems and body functions which are impaired,” Tuveson said. Janowitz is “trying to understand the essential details [of cachexia and other cancer conditions] so he can interrupt parts of it and give patients a better chance to go on clinical trials that would fight their cancer cells.”

A successful and driven scientist and medical doctor, Janowitz “is very talented and could be anywhere,” Tuveson said, and was pleased his new colleague decided to join CSHL.

Janowitz suggested that the combination of weight loss and loss of appetite in advancing cancer is “paradoxical. Why would you not be ravenously hungry if you’re losing weight? What is going on that drives this biologically seemingly paradoxical phenomenon? Is it reversible or modifiable?”

At this point, his research has shown that tumors can reprogram the host metabolism in a way that it “profoundly affects immunity and can affect therapy.” Reversing cachexia may require an anti-IL-6 treatment, with nutritional support.

As he looks for clinical cases that could reveal the role of this protein in cachexia, Janowitz has seen that patients with IL-6-producing tumors may have a worse outcome, a finding he is now seeking to validate.

At this point, treatment for other conditions with anti-IL-6 drugs has produced few side effects, although patients with advanced cancer haven’t received such treatment. Researchers know how to dose antibodies to IL-6 in the human body and treatment intervals would last for a few weeks.

Scientists have long thought of cancer as being like a wound that doesn’t heal. IL-6 is important in infections and inflammation.

Ultimately, Janowitz hopes to extend his research findings to other diseases and conditions. To do that, he would need to take small steps with one disease before expanding an effective approach to other conditions. “Are disease processes enacting parts of the biological response that are interchangeable?” he asked. “I think that’s the case.”

Eventually, Janowitz hopes to engage in patient care, but he first needs to obtain a license to practice medicine in the United States. He hopes to take the steps to achieve certification in the next year.

He plans to gather samples from patients on Long Island to study cancer and its metabolic consequences, including cachexia.

Several years down the road, the scientist hopes the collaborations he has with neuroscientists can reveal basic properties of cancer.

Tuveson believes Janowitz has “the potential of having a big impact individually as well as on everyone around him,” at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. “We are lucky to recruit him and want him to succeed and solve vexing problems so patients get better.”

Janowitz lives in Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory housing with his wife Clary and their three children, Viola, 6, Arthur, 4, and Albert, 2.

Clary is a radiation oncologist who hopes to start working soon at Northwell Health.

The Janowitz family has found Long Island “very welcoming” and appreciates the area’s “openness and willingness to support people who have come here,” he said. The family enjoys exploring nature.

The couple met at a production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” which was performed by a traveling cast of the Globe in Emmanuel College Gardens in Cambridge, England.

As with many others, Janowitz has had family members who are living with cancer, including both of his parents. His mother has had cancer for more than a decade and struggles with loss of appetite and weight. He has met many patients and their relatives over the years who struggle with these phenomena, which is part of the motivation for his dedication to this work.

Most cancer patients, Janowitz said, are “remarkable individuals. They adjust the way that they interact with the world and themselves when they get life changing diagnoses.” Patients have a “very reflected and engaged attitude” with the disease, which makes looking after them “incredibly rewarding.”

Jason Sheltzer, a fellow at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, and his partner Joan Smith, a senior software engineer at Google, have sought to use the genetic fingerprints of cancer to determine the likely course of the disease.

Jason Sheltzer, a fellow at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, and his partner Joan Smith, a senior software engineer at Google, have sought to use the genetic fingerprints of cancer to determine the likely course of the disease.