By Daniel Dunaief

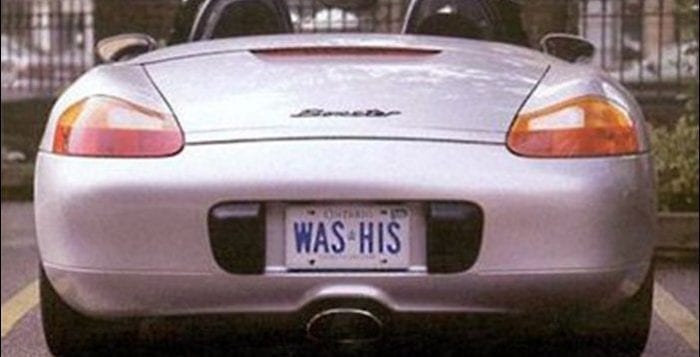

I appreciate the joy of vanity license plates. They are like small puzzles that allow me to ponder their meaning while I await two or three traffic lights so I can turn left.

Sometimes they are like good movies or artwork, allowing readers to come up with their own interpretation.

My wife and I will ask each other what the combination of letters and numbers mean, offering various guesses as if we were on a game show, trying to figure out whether the letters are a message or the celebration of a successful stock that made it possible for the person to buy that lovely car.

They can reveal a car owner’s passions, for skiing, golf or for a particular person. They can also suggest how someone got the car, where the person with the car came from or how many people are in a family.

Recently, I came to a traffic light and read a license plate that suggested a sad story. In an inconspicuous maroon car that I would have otherwise overlooked, the license plate had a message of animosity.

Wow, I thought. Who would advertise an identity linked to hatred? How sad that each time the person got in the car, the license plate reinforced his or her antipathy. What could have happened that made anger so much more important than any other message or than a random collection of letters and numbers?

Then again, maybe it’s the internet’s fault. Traveling along the internet superhighway, people can’t resist sharing their disdain for everyone and everything. Maybe the anger that follows us on roads and on the heavily trafficked internet world has converged, blending into one laser-like beam of focused enmity.

Then again, that’s probably a sociological cop-out. More likely, the car owner, whom I will call Joe, has a life-defining story he’s sharing through this license plate.

Joe may have loved someone deeply and for years. He made plans about where they’d live, how many kids they’d have, what they’d do on weekends and where they’d take this small joy mobile on vacations.

One day, however, she arrived at a prearranged dinner at a diner. She looked different. Her hair was longer and had been straightened. Instead of her worn North Face jacket, she was wearing a designer coat. Her purse, which Joe noticed when she placed it delicately on the table as if it were made of glass, had also changed.

“Hey,” Joe offered. “You look so different. What’s up?”

“I am different,” she smiled behind lipstick someone else had clearly applied. When she refused the bread she usually wolfed down, Joe became nervous.

“What’s different?”

“I won the lottery. I’m thinking of changing everything about my old life.”

“How much did you win?” a suddenly excited Joe asked.

“How much is irrelevant. I’ve decided to give you a parting gift. I’m going to buy you a new car.”

Joe didn’t know what to say. A car wasn’t what he wanted or expected. Then again, he didn’t want to walk away empty handed.

When it came time to pick out a license plate, Joe wanted just the right way to express his frustration over what could have been. He tried options the DMV denied. Finally, he came up with a message that encapsulated a road not taken for his life and his car. Joe regularly drives past the home of the former love of his life, hoping she notices him and the message on his license plate: EVEIH8U.

What are we doing? Why have we all agreed that 3-inch, cut grass should be the norm for American lawns? Why has this become the norm?

What are we doing? Why have we all agreed that 3-inch, cut grass should be the norm for American lawns? Why has this become the norm?