Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

Anthony Sciarratta’s The Letter (Post Hill Press) is a romance that examines both the power of faith and the strength of love.

Victor Esposito is a novelist who came to success in this thirties with each work featuring a very distinct female protagonist. His readers are unaware that she is not solely (or wholly) a creation of fiction: She is based on Eva Abrams, a vibrant and quirky individual he met by chance at concert just over a decade before. Eva, married with three children, was as drawn to Victor as he is to her. The two embarked on an intense but painfully platonic affair that lasted about year. “How could you see someone you know is perfect for you and never act on your feelings?”

After meeting two and three times a week, Eva broke it off with no explanation. During the ensuing years, the two had no contact. But she continued to be his muse, fueling his creative process: “To write a book about someone, to capture every groove of their face, curve of their body, and thought in their head, takes a great deal of studying … It was a special bond they shared that no person would ever come to understand.”

Now in his forties, Victor is a successful writer living in a luxurious Manhattan apartment. One night, he is shot during a bodega hold-up while saving a mother and child, resulting in his ending up in a coma. When Eva learns of this, she immediately leaves her Long Island home to be at his bedside. His mother, Barbara, immediately recognizes who this woman must be: “Victor has no children, no wife. You’re the only mark he left on this world. His life’s work is because of you.”

While sitting vigil, Eva examines the choices that have brought her to this juncture. Coming from an abusive and unstable childhood, Eva gave up her dreams of being a musician for the constancy of domestic life, married to the steady but disconnected Stanley. While being a mother gave her great joy, the marriage was never fulfilling resulting in a gnawing sense of loss.

Meanwhile, Victor does not regain consciousness. He is transported to a limbo where he, too, examines his life choices, in particular his brief relationship with Eva that motivated the change in his career from carpenter to writer. In this netherworld, he is guided by the enigmatic Benedict, who turns out to be someone from Victor’s earlier life. This half-world becomes populated with important figures of his and Eva’s histories.

Throughout, the characters are revealed in all their humanity, wearing their scars just below the surface. Sciarratta is not afraid to show confrontation or petty jealousies. These moments lend further dimension and texture.

Also present is the shadowy figure of Louis, who appears just before the bodega incident, and then returns in the book’s final chapters. He is the dark angel that lurks in the mind’s shadows: “I bet you have a lot of regrets now. You had everything: Money, health, and a great career. Being a good guy isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, huh, buddy?” He is a chilling figure that offers temptation and relief. This emissary of worst fears adds further conflict to the final road in Victor’s journey.

While the book is primarily a romance, it has elements of mystery as Sciarratta unravels his lead characters narratives.

His lovers’ consummation is unusual — if not unique — in its setting. It is both ardent and detailed. However, this does not in any way obscure the romantic force of the novel. Eva is his “North Star, guiding him through a depression by showing him what unconditional love feels like. She had looked past his sadness, despair, and anger to find a man with a beautiful soul …” A pair of socks given at a candlelit lunch in the park become a particularly compelling totem, representing a deeper caring than even the most fervid caress can show.

The story also nods to the solace drawn from belief: “Eva protected those she loved with a shroud of prayer, hoping that God would bless the lives that meant so much to her.” It is this mix of the spiritual and the visceral that are the foundations of both the story and the relationship. Whether drawn from religion or from nature, they find their way. In a touching episode, Victor sees himself in a wounded bird that he gently cradles in his hands; knowing that it wants to live but also accepting that death is part of the plane of human existence.

Ultimately, The Letter addresses the issue of soul mates. This is seeded at the outset and blooms in its epilogue. It is about the alchemy of love and its power to heal wounds, whether psychological or physical. It is a bold statement in a book that tells its story with straightforward passion and wide-eyed honesty.

The Letter is available at bookrevue.com, barnesandnoble.com and amazon.com.

This begins the dark heart of the book. Moskowitz is not the businessman he claims but, instead, a procurer. (Another nod towards Aleichem, this time his short story The Man from Buenos Aires.)

This begins the dark heart of the book. Moskowitz is not the businessman he claims but, instead, a procurer. (Another nod towards Aleichem, this time his short story The Man from Buenos Aires.)

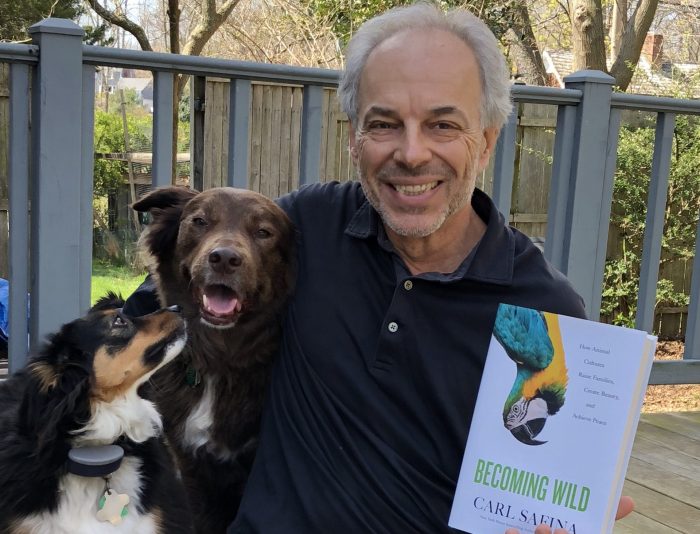

Safina divides the book into the study of sperm whales (families); scarlet macaws (beauty); and chimpanzees (peace). Each of the three sections is rich, detailed and engaging enough to be a book onto itself. He has brought them together under the umbrella of his exploration of culture.

Safina divides the book into the study of sperm whales (families); scarlet macaws (beauty); and chimpanzees (peace). Each of the three sections is rich, detailed and engaging enough to be a book onto itself. He has brought them together under the umbrella of his exploration of culture.

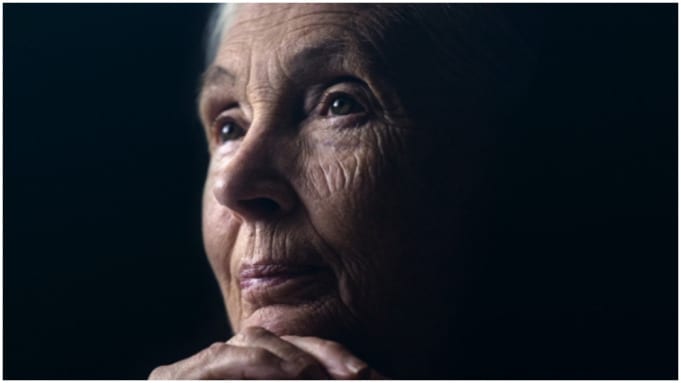

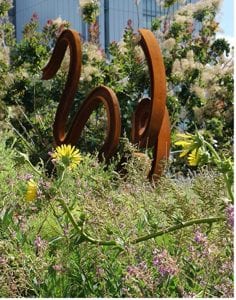

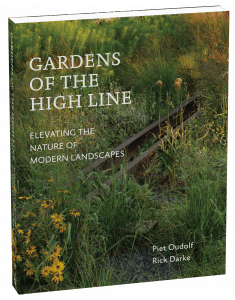

“Though it’s unlikely there will ever be another place quite like the High Line, it offers a wealth of insights and approaches worthy of emulation in gardens large or small, public or private. Authentic in spirit and execution, the High Line’s gardens offer a journey that is intriguing, unpredictable, imperfect, and, above all, transformative.”

“Though it’s unlikely there will ever be another place quite like the High Line, it offers a wealth of insights and approaches worthy of emulation in gardens large or small, public or private. Authentic in spirit and execution, the High Line’s gardens offer a journey that is intriguing, unpredictable, imperfect, and, above all, transformative.”

In an effort to present original content in a unique way, Theatre Three’s call for scripts garnered over 125 submissions in its first week that can be presented exclusively on-line. The pieces have been written or re-conceived for the online platform, and writers have used the constraints of the format as a different way to tell stories.

In an effort to present original content in a unique way, Theatre Three’s call for scripts garnered over 125 submissions in its first week that can be presented exclusively on-line. The pieces have been written or re-conceived for the online platform, and writers have used the constraints of the format as a different way to tell stories.

Quickly, the action shifts to Les Bosquets, Montfermeil’s most notorious and crime-ridden social estate. Police officer Stéphane Ruiz, an emotional and moral core as played in a brooding, heartfelt performance by Damien Bonnard, has arrived for his first day, having been transferred from Paris, to join the anti-crime brigade. He is placed with the high-strung, abusive, and sadistic Chris (Alexis Manenti, dangerously mercurial) and the more laid-back Gwada (understated but wholly engaging Djebril Zonga), who grew up in the neighborhood.

Quickly, the action shifts to Les Bosquets, Montfermeil’s most notorious and crime-ridden social estate. Police officer Stéphane Ruiz, an emotional and moral core as played in a brooding, heartfelt performance by Damien Bonnard, has arrived for his first day, having been transferred from Paris, to join the anti-crime brigade. He is placed with the high-strung, abusive, and sadistic Chris (Alexis Manenti, dangerously mercurial) and the more laid-back Gwada (understated but wholly engaging Djebril Zonga), who grew up in the neighborhood. Even after they locate Issa, it is an act of violence — revealed to be not as accidental as it first seems — that drives the latter part of the film. From then on, it is a race between the police officers and the various residents to track down the video from Buzz (wide-eyed and fearful Al-Hassan Ly), the boy whose drone recorded the incident. It all builds to a showdown that is both a literal and figurative conflagration.

Even after they locate Issa, it is an act of violence — revealed to be not as accidental as it first seems — that drives the latter part of the film. From then on, it is a race between the police officers and the various residents to track down the video from Buzz (wide-eyed and fearful Al-Hassan Ly), the boy whose drone recorded the incident. It all builds to a showdown that is both a literal and figurative conflagration.