By Elof Axel Carlson

Science is a way of knowing based on reason. That aspect of science would also apply to logic or the creation of mathematical fields. But when science is applied to the material world, reason is not sufficient. Modern science includes the use of data from observations and from the use of tools to produce data. A third aspect of science is characteristic of modern science. It is the design of experiments that predict what type of data will be found.

Science differs from revelation, tradition, authority or religious belief because these nonscientific ways that culture forms often require faith or do not attempt to apply science to their beliefs. This difference in interpreting the world around us allowed scientists to be skeptical, to require evidence and to apply more testing and tools to expand the applications of science to the universe and to life.

This resulted in many new fields of science. Astronomers purged themselves of astrology. Chemists purged themselves of alchemy. Medicine purged itself of quackery. All sciences rejected magic (except as entertainment) and wishful thinking.

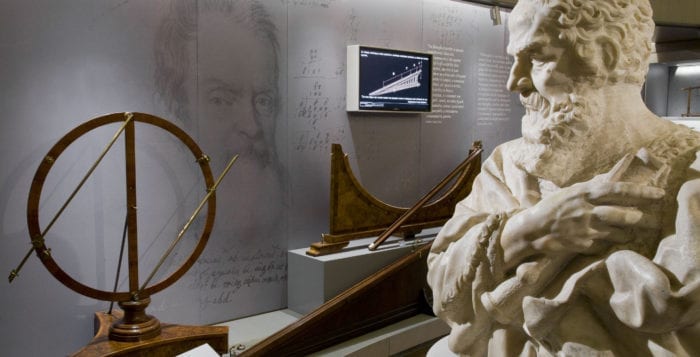

Modern science arose in Italy in the 1500s. We attribute to Galileo the origins of modern physics and astronomy. He worked out physical laws for falling bodies or bodies rolling down inclined planes. He introduced the mathematical equations to describe and to predict the time required and the distances involved in projectiles dropped, thrown or shot from cannons. He used the telescope he constructed to detect moons around Jupiter, phases of Venus, Saturn’s rings (they looked like ears to him) and mountains and craters on the moon.

Modern science arose in Italy because the first universities arose in Italy (the University of Bologna was the first in 1088). The Renaissance began in Italy with increased members of the middle class, formation of large cities, importing of knowledge from trade with Asia and Africa and an accumulation of wealth that was spent on architecture, the arts, hobbies, scholarship and curiosity for those with leisure time.

Artists like Albrecht Dürer went from Bavaria to Italy to study anatomy. William Harvey went from England to study medicine in Italy (Galileo was on the faculty when Harvey was a student) and brought back experimentation to the human body and the circulation of blood.

German universities benefited from sending students to Italy. In turn the Italian-trained German professors brought their skills to France. During the Enlightenment, French science flourished with Lavoisier in chemistry and Cuvier in biology. From France, science moved to the United States and the founding president of Johns Hopkins University, Daniel Coit Gilman, went to Europe and designed the American University model for its doctorate.

For the life sciences he recruited a student of Thomas Huxley’s, H. Newell Martin, and W. K. Brooks, one of the first American students of Louis Agassiz (famed for demonstrating and naming the Ice Age that covered large parts of Europe and North America). Martin and Brooks mentored T. H. Morgan. Morgan, at Columbia University, mentored H. J. Muller; and Muller, at Indiana University, mentored me.

While where a student goes for a doctorate may vary with time, over the past 500 years, the three features of science – reason, data collection and experimentation have not changed. Instead, they have provided enormous applications to our lives from computers to public health, to air flight, to transcontinental roads and railways. They have extended our life expectancy by more than 50 years since the Renaissance began. They allowed humans to walk on the moon and determine how many children to have and when to have them; and they allow us to eat fresh fruits and vegetables all year round.

Science has its limitations. It cannot design ideal governments, what values to live by, what purpose we choose for motivating us or supply the yearnings of wishful thinking (we will never be rid of all accidents, all diseases, or live forever). It co-exists with the humanities and the arts in filling out each generation’s expectations.

Elof Axel Carlson is a distinguished teaching professor emeritus in the Department of Biochemistry and Cell Biology at Stony Brook University.