By Daniel Dunaief

This is part 2 of a 2-part series.

Half of this year’s crop of recipients from New York State for Early Career Awards from the Department of Energy came from Brookhaven National Laboratory.

With ideas for a range of research efforts that have the potential to enhance basic knowledge and lead to technological innovations, two of the four winners earned awards in basic energy science, while the others scored funds from high energy physics and the office of nuclear physics.

“Supporting America’s scientists and researchers early in their careers will ensure the United States remains at the forefront of scientific discovery,” Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm said in a statement. The funding provides resources to “find the answers to some of the most complex questions as they establish themselves as experts in their fields.”

The DOE chose the four BNL recipients based on peer review by outside scientific experts. All eligible researchers had to have earned their PhDs within the previous 12 years and had to conduct research within the scope of the Office of Science’s eight major program areas.

Last week, the TBR News Media highlighted the work of Elizabeth Brost and Derong Xu. This week, we will feature the efforts of Esther Tsai and Joanna Zajac.

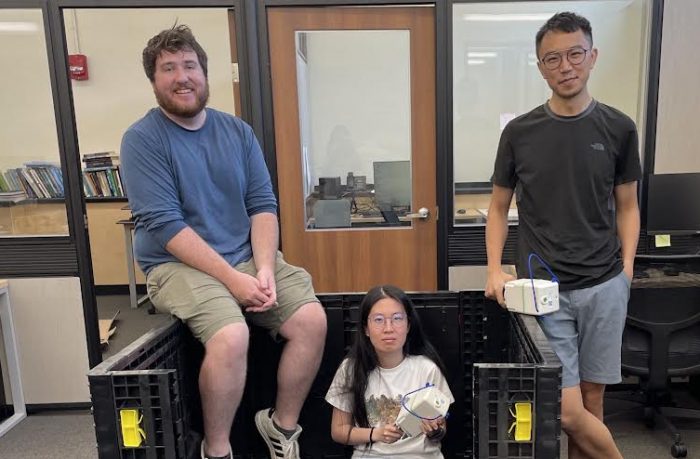

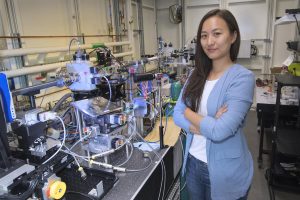

Esther Tsai

Listening to her in-laws argue over whom Alexa, the virtual assistant, listens to more, Esther Tsai had an idea for how to help the scientists who trek to BNL for their experiments. As a member of the beamline staff at the National Synchrotron Lightsource II, Tsai knew firsthand the struggles staff and visiting scientists face during experiments.

Artificial intelligence systems, she reasoned, could help bridge the knowledge gap between different domain experts and train students and future generations of scientists, some of whom might not be familiar with the coding language of Python.

In work titled “Virtual Scientific Companion for Synchrotron Beamlines,” Tsai, who is a scientist in the Electronic Nanomaterials Group of the Center for Functional Nanomaterials, is developing a virtual scientific companion called VISION. The system, which is based on a natural language based interaction, will translate English to programming language Python.

“VISION will allow for easy, intuitive and customized operation for instruments without programming experience or deep understanding of the control system,” said Tsai.

The system could increase the efficiency of experiments, while reducing bottlenecks at the lightsource, which is a resource that is in high demand among researchers throughout the country and the world.

Staff spend about 20 percent of user-support time on training new users, setting up operation and analysis protocols and performing data interpretation, Tsai estimated. Beamline staff often have to explain how Python works to control the instrument and analyze data.

VISION, however, can assist with or perform all of those efforts, which could increase the efficiency of scientific discoveries.

After the initial feelings of shock at receiving the award and gratitude for the support she received during the award preparation, Tsai shared the news with friends and family and then went to the beamline to support users over the weekend.

As a child, Tsai loved LEGO and jigsaw puzzles and enjoyed building objects and solving problems. Science offers the most interesting “puzzles to solve and endless possibilities for new inventions.”

Tsai thinks it’s exciting to make the imaginary world of Star Trek and other science fiction stories a reality through human-AI interactions.

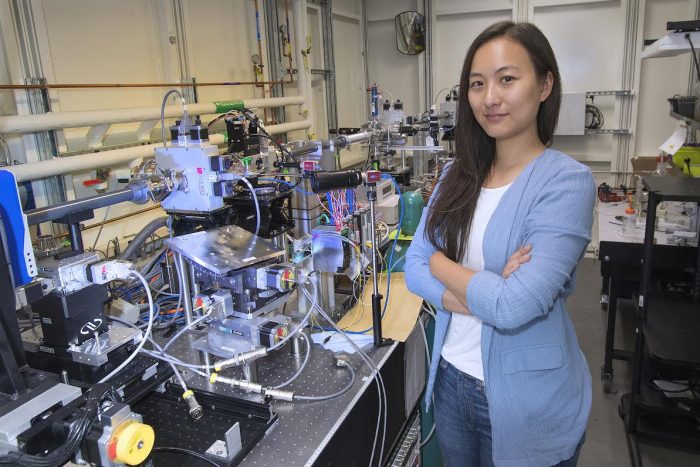

Joanna Zajac

A quantum scientist in the Instrumentation Division, Joanna Zajac is developing a fundamental understanding of fast light-matter interconnects that could facilitate long distance quantum networks.

Zajac will design and build systems that use quantum dots to generate single photos in the wavelengths used for optical telecommunications.

These quantum dots could potentially generate photons that would work at telecommunication and atomic wavelengths, which could reduce the losses to almost nothing when quantum information travels through the current optical fibers network. Losses are currently around 3.5 decibels per kilometer, Zajac explained in an email.

By coupling quantum dot single photons with alkali vapors, the light-matter interconnects may operate as a basis for quantum information, making up nodes of quantum network connected by optical links.

“Within this project, we are going to develop fundamental understanding of interactions therein allowing us to develop components of long-distance quantum networks,” Zajac said in a statement. “This DOE award gives me a fantastic opportunity to explore this important topic among the vibrant scientific community in Brookhaven Lab’s Instrumentation Division and beyond.”

Zajac explained that she was excited to learn that her project had been selected for this prestigious award. “I have no doubt that we have fascinating physics to learn,” she added.

In her first year, she would like to set up her lab space to conduct these measurements. This will also include development experimental infrastructure such as microscopes and table-top optical experiments. She hopes to have some proof-of-principle experiments.

She has served as a mentor for numerous junior scientists and calls herself “passionate” when it comes to working with students and interns.

Zajac, who received her master’s degree in physics from Southampton University and her PhD in Physics from Cardiff University, said she would like to encourage more women to enter the science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields, “as they are still underrepresented,” she said. “I would encourage them to study STEM subjects and ensure them that they will do just great.”

That process creates what is described as a reactive chlorine species, which is on the hunt for a positively charged particle, such as one of the four hydrogen atoms attached to carbon in methane.

That process creates what is described as a reactive chlorine species, which is on the hunt for a positively charged particle, such as one of the four hydrogen atoms attached to carbon in methane. When he’s not working, Mak enjoys boating and fishing. A native of Southern California, Mak is a commercial pilot, who also does some flying as a part of his research studies.

When he’s not working, Mak enjoys boating and fishing. A native of Southern California, Mak is a commercial pilot, who also does some flying as a part of his research studies.