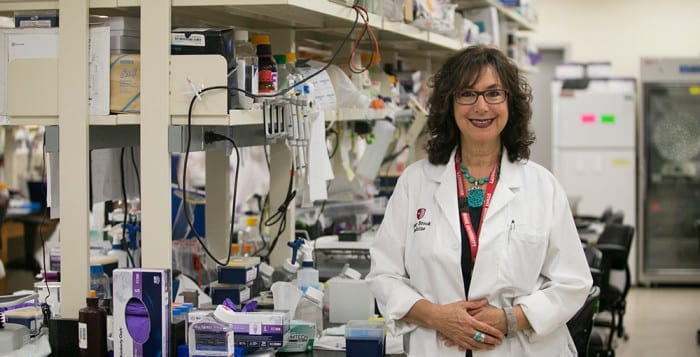

An award-winning scientist, grandmother, aunt, mother and wife, Dr. Lina Obeid, died Nov. 29 at the age of 64 after a recurrence of lung cancer.

Born in New York and raised in Lebanon, Obeid was a State University of New York distinguished professor of medicine and the dean of research at Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University, where she conducted research on cancer and aging. In 2015, she was named as one of The Village Times Herald’s People of the Year along with her husband Dr. Yusuf Hannun.

A Celebration of Life memorial service for Obeid will take place Dec. 7 at Flowerfield in St. James from 11 a.m. until 2:30 p.m. and will include remarks and a reception. Attendees are encouraged to wear bright colors.

SBU faculty appreciated Obeid’s scientific, administrative and mentoring contributions, as well as her engaging style.

Michael Bernstein, interim president of SBU, said Obeid was “very well liked and respected” and that her loss leaves a “big hole” at the university.

Obeid “oversaw our research programs, specifically the core facilities on which all our laboratory scientists depend, for sample analysis, for microscopy of cells” among other areas, Dr. Kenneth Kaushansky, dean of Renaissance School of Medicine wrote in an email.

He lauded Obeid’s personable approach, which he said, “rubbed off on many people,” creating a “renewed sense of optimism in our ability to impact all three missions: research, teaching and clinical care.”

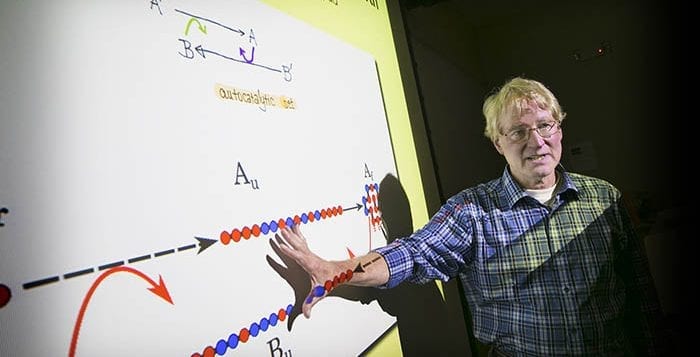

Obeid and Hannun, who is the director of the Stony Brook Cancer Center, knew each other in high school, started dating in medical school and were married for 36 years. The couple recently shared a Lifetime Achievement Award at the 16th International Conference on Bioactive Lipids in Cancer, Inflammation and Related Diseases in October. The award represents the first time a woman received this honor.

Supriya Jayadev, who was a graduate student in Hannun’s lab at Duke University and is the executive director of Clallam Mosaic in Port Angeles, Washington, called Obeid a “role model” for women in science. “Not only was she a strong leader with the ability to compete in a male-dominated field, but she retained her femininity and grace.”

Daniel Raben, a professor of biological chemistry at Johns Hopkins Medicine, has known Obeid and Hannun for more than two decades.

“She had a huge impact on the sphingolipid field because of the contribution she made,” Raben said. “It’s a huge loss. She was a giant.”

Dr. Maurizio Del Poeta, a professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at SBU, knew Obeid since 1995.

“I once asked her if she had any advice for my grants to get funded,” he recalled in an email. Obeid suggested she didn’t know how to get funded, but that his work wouldn’t get funded if he didn’t submit proposals.

She “never took ‘no’ for an answer. She would insist and insist and insist again until she [would] persuade you and get a ‘yes,’” he added.

Del Poeta said Obeid did a “marvelous” job enhancing research facilities, while she was a “caring physician” for veterans at the Northport VA Medical Center.

Obeid and Hannun were co-directors of a National Institutes of Health program in Cancer Biology and Therapeutics, which this year received a grant renewal for another five years.

Obeid’s daughter Marya Hannun recalled her mother as “warm, honest, and funny” without being cynical. Marya said her mother cared about everyone around her and was rooting for them to succeed.

“During my childhood, she taught me that nothing was impossible if you are determined and gutsy.”

— Mayra Hannun

“During my childhood, she taught me that nothing was impossible if you are determined and gutsy,” Marya Hannun wrote in an email.

She suggested her mother was passionate about food, which shaped how they lived and traveled. When the family visited Greece, Obeid swam out for sea urchins, cracked them on rocks and ate them on the beach. She was a passionate cook who learned from her mother, Rosette, who wrote a Palestinian cookbook.

The Hannun family laughs “about how we plan out holidays around food and spend

our meals talking about the next meals,” Marya wrote.

Obeid was part of one of the first class of women admitted into the International College High School. She earned her bachelor of arts at Rutgers University, but was also creative as a child and interested in fashion and design.

“Anyone who [saw] her wouldn’t be surprised,” Marya said.

Obeid is survived by her husband, her parents, Rosette and Sami, her nieces and nephews, her triplet children and her two grandchildren.

Obeid and Hannun’s daughter Reem is married to Dr. Khaled Moussawi and lives in Baltimore. Awni and his wife Kathy Hannun have two children, Evelyn and Yusuf, and live in New York City.

Binks Wattenberg, a professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Virginia Commonwealth University, believes that “people like [Obeid] only come along a few times in one’s lifetime.”

In an email, he recalled how she had a

“way of looking into your eyes and persuading you to do an experiment that she thought absolutely had to be done.” He appreciated her enthusiasm, which made Wattenberg feel as if he was doing “absolutely

essential work.”

Obeid regularly invited her researchers for meals at her house, where they felt as if they also joined the family, said Dr. Gerard Blobe, a professor of medicine at Duke University School of Medicine who earned his doctorate in Yusuf Hannun’s lab over 20 years ago.

In lieu of flowers, the family has asked for donations in Obeid’s name to the Stony Brook University Cancer Center. Potential donors can access the site at cancer.stonybrookmedicine.edu/giving.