By Daniel Dunaief

Though hampered by the pandemic in their direct contact with people who have autism, the founder of The Autism Initiative and research director Matthew Lerner along with the Head of Autism Clinical Education Jennifer Keluskar at Stony Brook University are managing to continue to reach out to members of the community through remote efforts. In a two-part series, Times Beacon Record News Media will feature Lerner’s efforts this week and Keluskar’s work next week.

Through several approaches, including improvisational theater, Matthew Lerner works with people who are on and off the autism spectrum on ways to improve social competence, including by being flexible in their approach to life.

In the midst of the ongoing pandemic, he has had to apply the same approach to his own work.

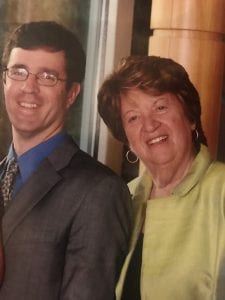

Lerner, who is an Associate Professor of Psychology, Psychiatry & Pediatrics in the Department of Psychology at Stony Brook University, recognizes that it’s difficult to continue a project called SENSE ® Theatre (for Social Emotional NeuroScience Endocrinology), where the whole function of the process is to provide in-person social intervention.

The SENSE Theater study is a multisite National Institute of Mental Health-funded project focused on assessing and improving interventions to improve social competence among adolescents with autism. The core involves in person intervention through group social interaction.

That, however, is not where the effort ends.“There are arms of that study that are more educational and didactic,” Lerner said. “We’re starting to think about how we could capitalize on that.”

In the ongoing SENSE effort, Lerner is coordinating with Vanderbilt University, which is the lead site for the study, and the University of Alabama.

Stony Brook is in active contact with the families who are participating in that effort, making sure they know “we are doing our best to get things up and running as quickly as possible,” Lerner said.

The staff is reaching out to local school districts as well, including the Three Village School District, with whom Lerner is collaborating on the project, to ensure that people know the effort will restart as soon as it’s “safe to be together again.”

Lerner is also the founder and Research Director of The Autism Initiative at SBU, which launched last year before the pandemic altered the possibilities for in-person contact and forced many people to remain at or close to home for much of the time. The initiative provides programs and services for the community to support research, social and recreational activities and other therapeutic efforts.

The Stony Brook effort initially involved video game nights, adult socials and book clubs. The organizers and participants in the initiative, however, have “stepped up in a huge way and have created, in a couple of weeks, an entirely new set of programming,” Lerner said.

This includes a homework support club, guidance, webinars and support from clinicians for parents, which address fundamental questions about how to support and adapt programs for people with autism. The group is keeping the book club active. The initiative at least doubled if not tripled the number of offerings, Lerner suggested.

Additionally, SBU has two grants to study a single session intervention adapted for teens with autism. The project has been running for about nine months. Lerner said they are looking to adapt it for online applications. For many families, such remote therapy would be a “real boon to have access to free treatment remotely,” he said.

Lerner had been preparing to conduct a study of social connections versus loneliness in teens or young adults with autism. Since COVID-19 hit, “we have reformulated that and are just about to launch” a longitudinal a study that explores the effects of the lockdown on well-being and stress for people who have autism and their families.

Lerner is looking at how the pandemic has enhanced the importance of resilience. He said these kinds of studies can perhaps “give us some insight when we return to something like normalcy about how to best help and support” people in the autism community. “We can learn” from the stresses for the community of people with autism during the pandemic.

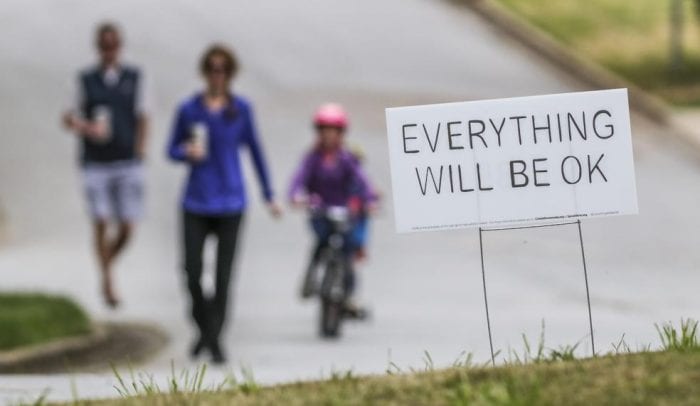

To be sure, the pandemic and the lockdown through New York Pause that followed hasn’t affected the entire community of people with autism the same way. Indeed, for some people, the new norms are more consistent with their behavioral patterns. “Some autistic teens and young adults have said things to me like, ‘I was social distancing before it was cool,’” Lerner said.

Another teenager Lerner interacted with regularly went to the bathroom several times to wash his hands. When Lerner checked in on him to see how he was doing amid the pandemic, he said, “I was made for this.”

Lerner also said people who aren’t on the spectrum may also gain greater empathy through the changes and challenges of their new routines. People find the zoom calls that involve looking at boxes of people on a full screen exhausting. After hours of shifting our attention from one box to another, some people develop “zoom fatigue.”

Lerner said someone with autism noted that this experience “may be giving the rest of us a taste of what it’s like for folks on the spectrum,” which could provide insights “we might not otherwise have.”

Even though some people with autism may feel like the rest of the world is mirroring their behavioral patterns, many people in and outside the autism community have struggled with the stresses of the public health crisis and with the interruption in the familiar structure of life.

The loss of that structure for many with autism is “really profound,” which is the much more frequent response, Lerner said. “More kids are telling us they are stressed out, while parents are saying the same thing.” In some sense, the crisis has revealed the urgency of work in the mental health field for people who are on and off the spectrum, Lerner said.

The studies in autism and other mental health fields that come out of an analysis of the challenges people face and the possible mental health solutions will likely include the equivalent of an asterisk, to capture a modern reality that differs so markedly from conditions prior to the pandemic. There may be a new reporting requirement in which researchers break down their studies by gender, age, race, ethnicity, income and “another variable we put in there: recruited during social isolation.”