By Daniel Dunaief

Athi Varuttamaseni is like an exterminator, studying ways pests can gain entry into a house, understanding the damage they can cause and then coming up with prevention and mitigation strategies. Except that, in Varuttamaseni’s case, the house he’s defending is slightly more important to most neighborhoods: They are nuclear power plants.

The pests he’s seeking to keep out or, if they enter, to expel and limit the damage, are cyberattackers, who might overcome the defenses of a plant’s digital operating system and cause a range of problems.

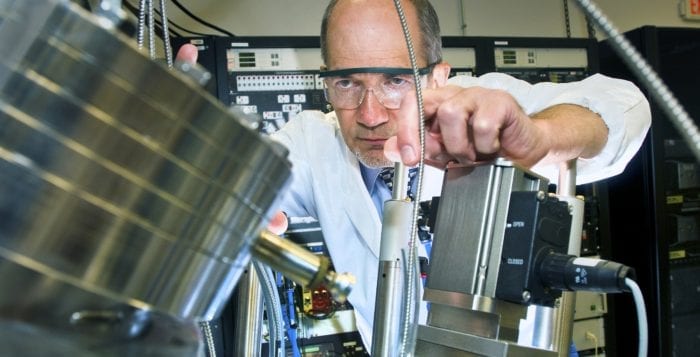

Varuttamaseni, an assistant scientist in the Nuclear Science & Technology Department at Brookhaven National Laboratory, started his career at BNL by modeling the failure of software used in nuclear power plant protection systems. Last year, he shifted toward cybersecurity. “We’re looking at what can go wrong with nuclear power plants” if they experience an attack on the control and protection systems, he said.

Varuttamaseni is part of a team that received a grant from the Department of Energy to look at the next generation of nuclear power plants, which are controlled and managed mostly by digital systems. A few existing plants are also looking to replace some of their analog systems with digital. “We asked what can go wrong if a hacker somehow managed to breach the outer perimeter and get in to control the system, or even if that is possible at all,” he said. By looking at potential vulnerabilities in the next generation of power plants, engineers can find a problem or potential problem ahead of time and can “go back to the drawing board to put in additional protection systems that could save the industry significant cost in the long run,” Varuttamaseni said.

Robert Bari, a physicist at BNL and a collaborator on the cybersecurity work, said Varuttamaseni, who is the lead investigator on the Department of Energy project, played “a major role” in putting together a recent presentation Bari gave at UC Berkeley that outlined some of the threats, impacts and technical and institutional challenges. The presentation included a summary and the next steps those running or designing nuclear power plants can take. Bari said it was a “delight” to collaborate with Varuttamaseni.

A colleague, Louis Chu, had recruited Varuttamaseni to work at BNL in another program, and Bari said he “recognized his abilities” and “we started to collaborate.” Varuttamaseni and Bari are going through a systematic analysis using logic trees and other approaches to explore vulnerabilities. The BNL team, which is collaborating with scientists at Idaho National Laboratory, shared the information and analysis they conducted with the Department of Energy and with an industrial collaborator.

In his second year of the work, Varuttamaseni said he is looking at the system level and is pointing out potential weaknesses in the design. He then shares that analysis with designers, who can shore up any potential problems. In the typical analysis of threats to nuclear power plants, the primary concern is of the release of radioactive material that could harm people who work at the plants or live in the communities around the facility.

Varuttamaseni, however, is exploring other implications, including economic damage or a loss of confidence in the industry. That includes the headline risk attached to an incident in which an attacker controlled systems other than a safety function and that are not critical to the operation of a plant. In addition to exploring vulnerabilities, Varuttamaseni is studying a plant’s response. Most of the critical systems are air-gapped, which means that the computer has no physical or wireless connection. While this provides a layer of protection against cyberattacks, it isn’t flawless or impenetrable. An upgrade of the hardware or patching of a hardware system might create just the kind of opening that would enable a hacker to pounce.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the industry are “aware of those scenarios,” Varuttamaseni said. “There are procedures in place and mitigation steps that are taken to prevent those kinds of attacks.” Ideally, however, the power plant would catch any would-be attacker early in the process. Varuttamaseni is working on three grants that are related to systems at nuclear power plants. In addition to cyberattacks, he is also analyzing software failures in the protection system and, finally, he’s also doing statistical testing of protection systems.

Varuttamaseni, who was born in Thailand, lives in Middle Island. He appreciates that Long Island is less crowded than New York City and describes himself as an indoor person. He enjoys the chance to read novels, particularly science fiction and mysteries. He also likes the moderate weather on Long Island compared to Bangkok, although threats from hurricanes are new to him. Next June, Varuttamaseni will present a paper on cybersecurity at the American Nuclear Society’s Nuclear Plant Instrumentation, Control & Human-Machine Interface Technology Conference in San Francisco.

Varuttamaseni is “always on the lookout for insights into possible attack pathways that an attacker could come up with,” he said. “The mitigating factor of my work is that we’re looking at a longer-term problem. There’s still time to [work with] many of these potential vulnerabilities.”