By Daniel Dunaief

The Ukranian-born Alex Orlov, who is an associate professor of materials science and chemical engineering at Stony Brook University, helps officials in a delicate balancing act.

Orlov, who is a member of the US-EU working group on Risk Assessment of Nanomaterials, helps measure, monitor and understand the hazards associated with nanoparticles, which regulatory bodies then compare to the benefit these particles have in consumer products.

“My research, which is highlighted by the European Union Commission, demonstrated that under certain conditions, [specific] nanoparticles might not be safe,” Orlov said via Skype from Cambridge, England, where he has been a visiting professor for the past four summers. For carbon nanotubes, which are used in products ranging from sports equipment to vehicles and batteries, those conditions include exposure to humidity and sunlight.

“Instead of banning and restricting their production” they can be reformulated to make them safer, he said.

Orlov described how chemical companies are conducting research to enhance the safety of their products. Globally, nanotechnology has become a growing industry, as electronics and drug companies search for ways to benefit from different physical properties that exist on a small scale. Long Island has become a focal point for research in this arena, particularly at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials and the National Synchrotron Light Source II at Brookhaven National Laboratory.

Indeed, Orlov is working at the University of Cambridge to facilitate partnerships between researchers in the chemistry departments of the two universities, while benefiting from the facilities at BNL. “We exchange some new materials between Cambridge and Stony Brook,” he said. “We use BNL to test those materials.”

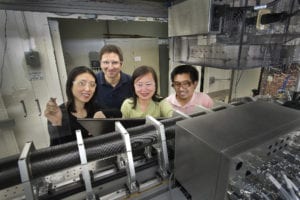

BNL is an “essential facility,” Orlov said, and is where the postdoctoral student in his lab and the five graduate students spend 30 to 60 percent of their time. The data he and his team collect can help reduce risks related to the release of nanomaterials and create safer products, he suggested.

“Most hazardous materials on Earth can be handled in a safe way,” Orlov said. “Most scientific progress and environmental protection can be merged together. Understanding the environmental impact of new technologies and reducing their risks to the environment should be at the core of scientific and technological progress.”

According to Orlov, the European Union spends more money on technological safety than the United States. European regulations, however, affect American companies, especially those that export products to companies in the European Union.

Orlov has studied how quickly toxic materials might be released in the environment under different conditions.

“What we do in our lab is put numbers” on the amount of a substance released, he said, which informs a more quantitative understanding of the risks posed by a product. Regulators seek a balance between scientific progress and industrial development in the face of uncertainty related to new technologies.

As policy makers consider the economics of regulations, they weigh the estimated cost against that value. For example, if the cost of implementing a water treatment measure is $3 million and the cost of a human life is $7 million, it’s more economical to create a water treatment plan.

Orlov teaches a course in environmental engineering. “These are the types of things I discuss with students,” he said. “For them, it’s eye opening. They are engineers. They don’t deal with economics.”

In his own research, Orlov recently published an article in which he analyzed the potential use of concrete to remove pollutants like sulfur dioxide from the air. While concrete is the biggest material people produce by weight and volume, most of it is wasted when a building gets demolished. “What we discovered,” said Orlov, who published his work in the Journal of Chemical Engineering, “is that if you take this concrete and expose new surfaces, it takes in pollutants again.”

Fotis Sotiropoulos, the dean of the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences at SBU, said Orlov has added to the understanding of the potential benefits of using concrete to remove pollutants.

Other researchers have worked only with carbon dioxide, and there is “incomplete and/or even nonexistent data for other pollutants,” Sotiropoulos explained in an email. Orlov’s research could be helpful for city planners especially for end-of-life building demolition, Sotiropoulous continued. Manufacturers could take concrete from an old, crushed building and pass waste through this concrete in smokestacks.

To be sure, the production of concrete itself is energy intensive and generates pollutants like carbon dioxide and nitrogen dioxide. “It’s not the case that concrete would take as much [pollutants] out of the air as was emitted during production,” Orlov said. On balance, however, recycled concrete could prove useful not only in reducing waste but also in removing pollutants from the air.

Orlov urged an increase in the recycling of concrete, which varies in the amount that’s recycled. He has collaborated on other projects, such as using small amounts of gold to separate water, producing hydrogen that could be used in fuel cells.

“The research showed a promising way to produce clean hydrogen from water,” Sotiropoulos said.

As for his work at Cambridge, Orlov appreciates the value the scientists in the United Kingdom place on their collaboration with their Long Island partners.

“Cambridge faculty from disciplines ranging from archeology to chemistry are aware of the SBU/BNL faculty members and their research,” Orlov said. A resident of Smithtown, Orlov has been on Long Island for eight years. In his spare time, he enjoys hiking and exploring new areas. As for his work, Orlov hopes his work helps regulators make informed decisions that protect consumers while making scientific and technological advances possible.