By Daniel Dunaief

What changes and how it changes from moment to moment can be the focus of curiosity — or survival. A zebra in Africa needs to detect subtle shifts in the environment, forcing it to focus on the possibility of a nearby predator like a lion.

Similarly, scientists are eager to understand, on an incredibly small scale, the way important participants in chemical processes change as they create products, remove pollutants from the air or engines or participate in reactions that make electronic equipment better or more efficient.

Throughout a process, a catalyst can alter its shape, sometimes leading to a desired product and other times resulting in an unwanted dead end. Understanding the structural forks in the road during these interactions can enable researchers to create conditions that favor specific structural configurations that facilitate particular products.

First, however, scientists need to see how catalysts involved in these reactions change.

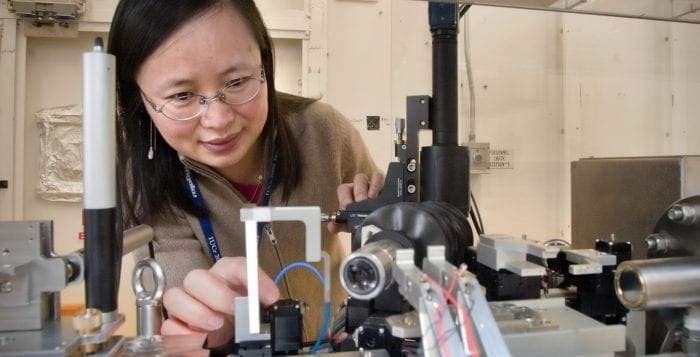

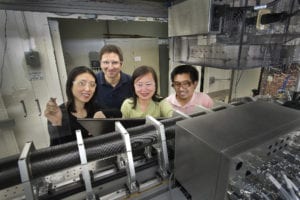

That’s where Anatoly Frenkel, a professor at Stony Brook University’s Department of Materials Science and Chemical Engineering with a joint appointment in Brookhaven National Laboratory’s Chemistry Division, and Janis Timosheko, a postdoctoral researcher in Frenkel’s lab, come in.

Working with Deyu Lu at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials and Yuwei Lin and Shinjae Yoo, both from BNL”s Computational Science Initiative, Timoshenko leads a novel effort to use machine learning to observe subtle structural clues about catalysts.

“It will be possible in the future to monitor in real time the evolution of the catalyst in reaction conditions,” Frenkel said. “We hope to implement this concept of reaction on demand.”

According to Frenkel, beamline scientist Klaus Attenkofer at BNL and Lu are planning a project to monitor the evolution of catalysts in reaction conditions using this method.

By recognizing the specific structural changes that favor desirable reactions, Frenkel said researchers could direct the evolution of a process on demand.

“I am particularly intrigued by a new opportunity to control the selectivity (or stability) of the existing catalyst by tuning its structure or shape up to enhance formation of a desired product,” he explained in an email.

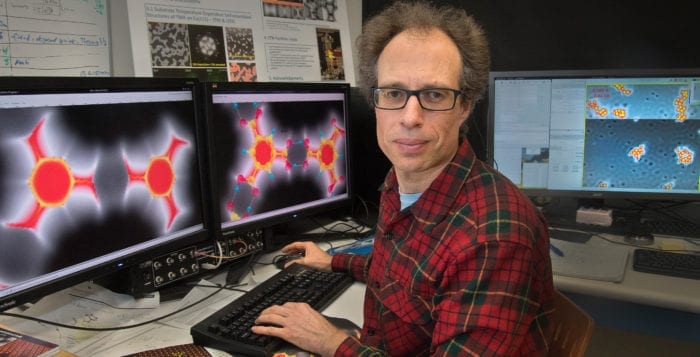

The neural network the team has created links the structure and the spectrum that characterizes the structure. On their own, researchers couldn’t find a structure through the spectrum without the help of highly trained computers.

Through machine learning, X-rays with relatively lower energies can provide information about the structure of nanoparticles under greater heat and pressure, which would typically cause distortions for X-rays that use higher energy, Timoshenko said.

The contribution and experience of Lin, Yoo and Lu was “crucial” for the development of the overall idea of the method and fine tuning its details, Timoshenko said. The teaching part was a collective effort that involved Timoshenko and Frenkel.

Frenkel credits Timoshenko for uniting the diverse fields of machine learning and nanomaterials science to make this tool a reality. For several months, when the groups got together for bi-weekly meetings, they “couldn’t find common ground.” At some point, however, Frenkel said Timoshenko “got it, implemented it and it worked.”

The scientists used hundreds of structure models. For these, they calculated hundreds of thousands of X-ray absorption spectra, as each atom had its own spectrum, which could combine in different ways, Timoshenko suggested.

They back-checked this approach by testing nanoparticles where the structure was already known through conventional analysis of X-ray absorption spectra and from electron microscopy studies, Timoshenko said.

The ultimate goal, he said, is to understand the relationship between the structure of a material and its useful properties. The new method, combined with other approaches, can provide an understanding of the structure.

Timoshenko said additional data, including information about the catalytic activity of particles with different structures and the results of theoretical modeling of chemical processes, would be necessary to take the next steps. “It is quite possible that some other machine learning methods can help us to make sense of these new pieces of information as well,” he said.

According to Frenkel, Timoshenko, who transferred from Yeshiva University to Stony Brook University in 2016 with Frenkel, has had a remarkably productive three years as a postdoctoral researcher. His time at SBU will end by the summer, when he seeks another position.

A native of Latvia, Timoshenko is married to Edite Paule, who works in a child care center. The scientist is exploring various options after his time at Stony Brook concludes, which could include a move to Europe.

A resident of Rocky Point during his postdoctoral research, Timoshenko described Long Island as “extremely beautiful” with a green landscape and the nearby ocean. He also appreciated the opportunity to travel to New York City to see Broadway shows. His favorite, which he saw last year, is “Miss Saigon.”

Timoshenko has dedicated his career to using data analysis approaches to understanding real life problems. Machine learning is “yet another approach” and he would like to see if this work “will be useful” for someone conducting additional experiments, he said.

At some point, Timoshenko would also like to delve into developing novel materials that might have an application in industry. The paper he published with Frenkel and others focused only on the studies of relatively simple monometallic particles. He is working on the development of that method to analyze more complex systems.

This work, he suggested, is one of the first applications of machine learning methods for the interpretation of experimental data, not just in the field of X-ray absorption spectroscopy. “Machine learning, data science and artificial intelligence are very hot and rapidly developing fields, whose potential in experimental research we have just started to explore.”