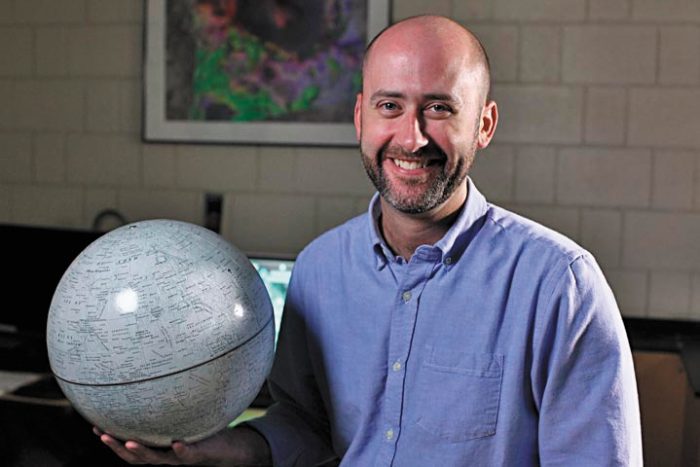

SBU’s Timothy Glotch and the case of the inexplicable lunar granite

By Daniel Dunaief

It’s almost easier to figure out what makes Earth unique among the planets than it is to list the ways humans are unique among Earth’s inhabitants. Earth is, after all, the only blue planet, filled with water from which humans, and so many other creatures, evolved. It is also the only planet on which seven enormous plates deep beneath the surface move. These unique features have led scientists to expect certain features that give Earth its unique geological footprint.

Not so fast.

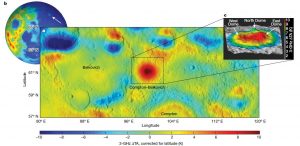

According to a recent paper in the high-profile journal Nature in which Timothy Glotch, Professor of Geosciences at Stony Brook University, was a co-author, the moon has a vast swath of over 50 kilometers of granite in the Compton-Belkovich Volcanic complex, which is on the its far side.

Usually formed from plate tectonics of water bearing magma, the presence of this granite, which appears in greater quantities around the Earth, is something of a planetary mystery.

“Granites are extremely rare outside of Earth,” said Glotch. “Its formation process must be so different, which makes them interesting.”

The researchers on this paper, including lead author Matt Siegler, a scientist at the Planetary Science Institute, suggest a range of possibilities for how the granite formed. Over three billion years ago, the moon, which, like the Earth, is over 4.5 billion years old, had lava that erupted to form the Compton-Belkovich Volcanic Complex, or CBVC. Researchers think most volcanic activity on the moon ended about two billion years ago.

The magma formed as a result of a melting of a small portion of the lunar mantle. Melting could have been caused by the addition of water or the movement of hot material closer to the surface. Scientists are not completely sure about the current nature of the lunar core.

As for the granite, it might have come from fractionation, in which particles separate during a transition from different phases, in this case from a hot liquid like magma to a solid.

Additionally, the presence of granite could suggest that some parts of the moon had more water than others.

“There are other geochemical arguments you could make,” Glotch said. “What we really need are to find more samples and bring them back to Earth.”

The analysis of granite on the moon came from numerous distant sources, as well as from the study of a few samples returned during the Apollo space missions. The last time people set foot on the moon was on the Apollo 17 mission, which returned to Earth on Dec. 19, 1972.

A 10-year process

The search and study of granite on the moon involved a collaboration between Glotch and Siegler, who have known each other for about 18 years. The two met when Glotch was a postdoctoral researcher and Siegler was a graduate student.

In 2010, Glotch published a paper in the journal Science in which he identified areas that have compositions that are similar to granite, or rhyolite, which is the volcanic equivalent.

Since that paper, Glotch and others have published several research studies that have further characterized granitic or rhyolitic materials, but those are “still relatively rare,” Glotch said.

Long distance monitoring

Led by Siegler and his postdoctoral researcher Jiangqing Feng, the team gathered information from several sources, including microwave data from Chinese satellites, which are sensitive to the heat flow under the surface.

The team also used the Diviner Lunar Radiometer Experiment, which is a NASA instrument on the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, that measures surface temperatures.

Part of the discovery of the silicic sites on the moon comes from the identification of the element thorium, which the Lunar Prospector Gamma Ray Spectrometer found. Similar to uranium or plutonium, thorium is radioactive and decays.

Another piece of data came from the Grail mission, which measures the lunar gravity field.

Glotch suggested that the study involved a “daisy chain of observations.” In his role, he tried to identify sites that might be rich in granite, while Siegler applied new data to these areas to learn more about the underground volcanic plumbing.

In addition to doing long distance monitoring, Glotch engages in long distance recreational activities. The Stony Brook professor is preparing for a November 11th run in Maryland that will cover 50 miles. He expects it will take him about 10 or 11 hours to complete.

Looking at other planets

By analyzing granite on the moon, which could reveal its early history, geologists might also turn that same analysis back to the Earth.

“Can we use the results of this study to take a more nuanced view of granite formations on Earth or other bodies in our solar system?” Glotch asked. “We can learn a lot, not just about the moon, but about planetary evolution.”

NASA is planning a DAVINCI+ mission to Venus in the coming decade, while a European mission is also scheduled for Venus. Some researchers have suggested that Venusian terrains, which are referred to as Tesserae, might be granitic.

“If Venus has continent-like structures made of granite, that’s interesting, because Venus does not appear to have plate tectonics either,” Glotch said.

Closer to Earth, some upcoming missions may offer a better understanding of lunar granite. The first is a small orbiter called Lunar Trailblazer that will have sensitive remote instruments. The second is a part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services program, which will include a small lander and rover that will land on the Gruithuisen Domes.

Conference in Italy

In the shorter term, Glotch and Siegler plan to attend the 10th Hutton Symposium in Italy.

Glotch is eager to discuss the work with researchers who are not planetary scientists to “get their take on this.”

He is excited by the recent planetary decadal survey, which highlighted several priorities, which include lunar research.

In his opinion, Glotch believes the survey includes more high priority lunary science than in previous such surveys.

Countries including India, China, Israel and Japan have a renewed national interest in the moon. South Korea currently has an orbiter at the moon.

All this attention makes the moon a “really good target for U.S. science to maintain our leadership position, as well as providing a tool for geopolitical cooperation,” Glotch added.