By Daniel Dunaief

Replacing batteries in a flashlight or an alarm clock requires simple effort and generally doesn’t carry any risk for the device. The same, however, can’t be said for battery-operated systems that go in human bodies and save lives, such as the implantable cardiac defibrillator, or ICD.

Earlier versions of these life-saving devices that restore a normal heart rhythm were large and clunky and required a change of battery every 12 to 18 months, which meant additional surgeries to get to the device.

That’s where Esther Takeuchi, who is now Stony Brook University’s William and Jane Knapp Endowed Chair in Energy and the Environment and the chief scientist of the Energy Sciences Directorate at Brookhaven National Laboratory, has made her mark. In the 1980s, working at a company called Greatbatch, Takeuchi designed a battery that was much smaller and that lasted as long as five years. The battery she designed was a million times higher power than a pacemaker battery.

For her breakthrough work on this battery, Takeuchi has received numerous awards. Recently, the European Patent Office honored her with the 2018 innovation prize at a ceremony in Paris. Numerous high-level scientists and public officials attended the award presentation, including former French Minister of the Economy Thierry Breton, who is currently the CEO of Atos, and the Secretary General of the International Organisation of Francophony Michaëlle Jean.

Takeuchi was the only American to win this innovation award this year.

Takeuchi’s work is “the epitome of innovation, as demonstrated in this breakthrough translational research for which she was recognized,” Dr. Samuel L. Stanley Jr., the president of Stony Brook and board chair of Brookhaven Science Associates, which manages Brookhaven National Laboratory. “Her star keeps getting brighter, and I’m proud that she is part of the Stony Brook University family.”

As a winner of this award, Takeuchi joins the ranks of other celebrated scientists, including Shuji Nakamura, who won the European Inventor Award in 2007 and went on to win the Nobel Prize in physics, and Stefan Hell from Germany, whose European Inventor Award predated a Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Among the over 170 innovators who have won the award, some have worked on gluten substitutes from corn, some have developed drugs against multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis, and some have developed soft close furniture hinges.

“The previous recipients have had substantial impact on the world and how we live,” Takeuchi explained in an email. “It is incredible to be considered among that group.” Nominated for the award by a patent examiner from the European Patent Office, she described the award as an “honor” for the global recognition.

The inventor award is a symbolic prize in which the recipients receive attention for their work, explained Rainer Osterwalder, the director of media relations at the European Patent Office.

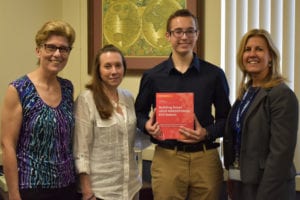

Takeuchi was one of four women to receive the award this year — the largest such class of women innovators.

“It was very meaningful to see so many accomplished women be recognized for their contributions,” she explained. “I was delighted to meet them and make some additional contacts with female innovators as well.”

About half the researchers in her lab, which currently includes three postdoctoral researchers and usually has about 12 to 16 graduate students, are women. Takeuchi has said that she likes being a role model for women and that she hopes they can see how it is possible to succeed as a scientist.

Implantable cardiac defibrillators are so common in the United States that an estimated 10,000 people receive them each month.

Indeed, while she was at the reception for an awards ceremony attended by over 600 people, Takeuchi said she met someone who had an ICD.

“It is very rewarding to know that they are alive due to technology and my contributions to the technology,” she explained.

Takeuchi said that many people contributed to the battery project for the ICD over the years who were employed at Greatbach. These collaborators were involved in engineering, manufacturing, quality and customer interactions, with each aspect contributing to the final product.

The battery innovation stacks alternating layers of anodes and cathodes and uses lithium silver vanadium oxide. The silver is used for high current, while the vanadium provides long life and high voltage.

Takeuchi, who earned her bachelor’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania and her doctorate from Ohio State University, has received over 150 patents. The daughter of Latvian emigrants, she received the presidential level National Medal of Technology and Innovation from Barack Obama and has been inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

Takeuchi continues to push the envelope in her energy research. “We are now involved in thinking about larger scale batteries for cars and ultimately for the grid,” she wrote in an email. “Further, we have demonstrated methods that allow battery components to be regenerated to extend their use. This could potentially minimize batteries going into land fills in the future.”

Takeuchi is one of a growing field of scientists who are using the high-tech capabilities of the National Synchrotron Light Source II at BNL, which allows her to see inside batteries as they are working.

“We recently published a paper where we were able to detect the onset of parasitic reactions,” she suggested, which is “an important question for battery lifetime.”

In the big picture, the scientist said she is balancing between power and energy content in her battery research.

“Usually, when cells need to deliver high power, the energy content goes down,” she said. “The goal is to have high energy and high power simultaneously.”