Making Democracy Work: A Thanksgiving postscript

By Lisa Scott

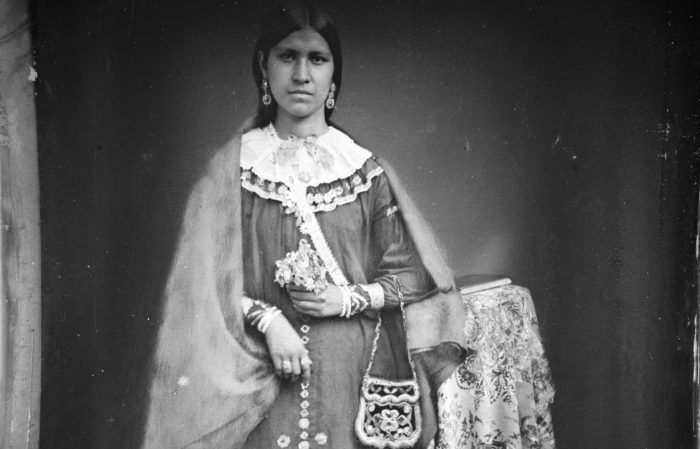

November for most of us is a time to celebrate our democracy by voting. And later that month we conjure Pilgrims and Indians celebrating harvest plentitude in peace, as we similarly gather with friends and family to feast and give thanks. But today when vocal individuals and groups are arguing that history and culture are controversial subjects, it’s important to remind us all that there is much more about Native Americans that we can learn from and that should be shared.

American Indian Day was first celebrated in New York 107 years ago — after Red Fox James (a member of the Blackfoot Nation) rode across our country seeking approval from 24 state governments to have a day to honor American Indians. But it wasn’t until 1990 that Pres. George H.W. Bush signed a joint congressional resolution designating November “National American Indian Heritage Month.”

The U.S. Census Bureau conducted population surveys which were released as part of their 2020 census: the U.S. American Indian and Alaska Native population (9.7 million in 2020) is one of the six major race categories defined by the US Office of Management and Budget. There were 1.5 million people who identified as Cherokee. That group has a tragic history, since they and the other “Five Civilized Tribes” of what’s referred to now as the American Deep South were subject to Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830 leading to the “Trail of Tears.”

This was an effort to forcibly relocate tribes/sovereign nations to Oklahoma and for the federal and state governments to dissolve their tribal boundaries and annex their lands. In today’s world, it can be termed “ethnic cleansing” and it anticipated the U.S. Indian reservation system. And the fighting over Indian lands was not only a 19th century blot on our history.

Killers of the Flower Moon (book by David Grann, as well as the recent film) recounts the true story of how a white businessman and self-proclaimed “true friend” of the Osage Nation orchestrated the brutal murders of numerous members of the tribe in early 1920s Oklahoma after big oil deposits were discovered beneath their land.

The ”Trail of Tears” tragedy and the legacy of government disregard (in spite of court decisions supporting tribal land sovereignty and finding against federal and state land seizures) continues to the current day. For example, the Shinnecock Nation continue their efforts to regain control over their ancestral land. The Shinnecock Indian Nation is one of the oldest self-governing tribes in the State of New York and was formally recognized by the United States federal government as the 565th federally recognized tribe on October 1, 2010.

But Governor Hochul recently vetoed the Montaukett tribe’s state-recognition bill, which had passed the NYS legislature unanimously early in 2023, citing a 1910 judicial decision which claimed that the Montaukett community no longer functioned as a governmental unit in the state. Historian John Strong called those 1910 rulings “racist.” In 1998, a Newsday investigation unearthed documents that appear to be “deceit, likes and possible forgery” in deals that wrested tribal lands from the Montauketts and the Shinnecock Indian Nation.

Women’s Suffrage leaders in upstate New York in the mid-19th century were strongly influenced by the Native Americans — specifically the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) whose tribal government was organized to maintain a balance of equality between men and women. There was a wide range of information in local newspapers like the Syracuse Standard, creating a sophisticated understanding of Haudenosaunee culture and tribal government. Also there was a great deal of personal interaction; friendship and visiting were commonplace activities.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Matilda Joslyn Gage, as major theoreticians of the woman’s rights movement, claimed that the society in which they lived was based on the oppression of women. However, their neighbors, Haudenosaunee society, was organized to maintain a balance of equality between women and men; women had decisive political power, control of their bodies, control of their own property. custody of the children they bore, the power to initiate divorce, satisfying work, and a society generally free of rape and domestic violence. Women chose their chief, held key political offices, and decision making was by consensus. Thus those early feminists believed women’s liberation was possible because they knew liberated women who possessed rights beyond their wildest imagination — Haudenosaunee women.

Lisa Scott is president of the League of Women Voters of Suffolk County a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that encourages the informed and active participation of citizens in government and influences public policy through education and advocacy. For more information, visit https//my.lwv.org/new-york/suffolk-county.