Faced with High Ventilator Demand, SBU Builds its Own in 10 Days

Working against time and a potential shortage of life-saving ventilators, Stony Brook University scientists designed their own version, which they hoped no one would have to use.

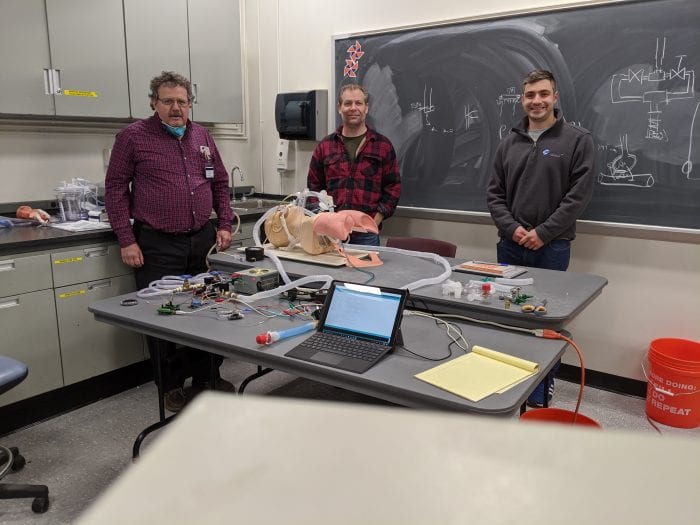

In the course of 10 days, a team led by Jon Longtin, College of Engineering and Applied Sciences Associate Dean of Research and Entrepreneurship and professor of mechanical engineering, designed, built and tested a cheaper and easier ventilator, which they called CoreVent2020. They have spoken with a company in Shirley called Biodex Medical Systems, which could make as many as 30 of the originally crafted machines per day.

“It was an all-encompassing task,” Longtin said. “When we started this, COVID-19 cases were growing exponentially in the New York area. By following the curve at that point, we were going to run out of ventilators in a matter of one or two weeks.”

Indeed, just a few weeks ago, Suffolk County and New York State were still climbing the curve, without knowing when the peak would arrive. That meant that each day, the number of people hospitalized increased dramatically, as did the number of people who needed ventilators in the Intensive Care Unit.

The parts for the system Longtin, John Brittelli, a clinical professor in the Respiratory Care Program, and Dmitris Assanis, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Stony Brook, created cost about $2,000. This includes the cost for the arduino control panel, which is a computer board people have programmed to run their washing machines and to turn on lamps. The total cost compares with a price tag of about $30,000 for a regular ventilator.

The CoreVent 2020 favors a hospital setting, Longtin said, because it runs on medical compressed oxygen and compressed air.

“Most hospitals have compressed air, which we were able to use to make the design much simpler,” Longtin said.

Chris Paige, an anesthesiologist at Stony Brook University Hospital who worked on the ventilator, coined the term CoreVent, which suggests a “core” set of needed capabilities, but nothing more, Longtin explained in an email.

The researchers wanted to create a machine that didn’t have any proprietary parts, which would make the manufacture and distribution of the system considerably easier. The researchers wanted to make sure they could get the parts they needed and could still move forward even if a particular part from a specific manufacturer wasn’t available.

“Anything we used, we could buy from a number of different suppliers,” Longtin said. “As long as the specifications were the same, the design was simple and reliable.”

Longtin said the limits of time and resources, akin to the engineers at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration who helped bring home the damaged Apollo 13 rocket with its three-member crew, were omnipresent in designing and building the alternative ventilator system.

Longtin was grateful for the help and support of people in the engineering and medical side.

Longtin said he appreciated the opportunity to work together with his colleagues in the medical community and not only to build this alternative ventilator but also to build relationships across the Stony Brook community.