A writer, poet and professor is enjoying freedom once again.

Cameroon police detained Patrice Nganang, professor of Cultural Studies and Comparative Literature at Stony Brook University, as he was leaving the country for Zimbabwe at Douala International Airport early in December. The detainment came after the Cameroonian-native and United States citizen published an article on the website Jeune Afrique. In the piece in question, the professor was critical of Cameroon President Paul Biya’s administration’s approach to the ongoing instability in Anglophone regions of Cameroon. Many have criticized the government’s response to citizen’s protests regarding marginalization in the regions

Robert Harvey, a distinguished professor at SBU, said Nganang’s wife Nyasha notified him Dec. 27 of her husband’s hearing suddenly being changed from Jan. 19 to the morning of the 27th and that he was released and all charges dropped.

“No doubt all the pressure mobilized from various sectors helped,” Harvey said.

Dibussi Tande, a friend of Nganang’s for 10 years and one of the administrators of the Facebook page, Free Patrice Nganang, which has gained more than 2,200 followers, echoed Harvey’s sentiments.

“It is a feeling of relief and pride in the amazing work done by a global team of human rights activists, journalists, civil society organizations, friends, family, etc., to bring pressure to bear on the government of Cameroon to set him free,” Tande said.

In a phone interview after his release, Nganang agreed that the pressure from outside of Cameroon, especially from the United States, played a part in his being set free earlier and being treated well while in prison. He even was given meals from outside of the jail and didn’t have to eat prison food.

“The pressure not only led to my early release, it was also such that it gave me a better condition in jail so it made it possible for me to have a more humane condition,” Nganang said.

Among the charges Nganang faced were making a death threat against the president; forgery and use of forgery, due to the professor having a Cameroonian passport despite being a U.S. citizen, as the country does not recognize dual citizenship; and illegal immigration due to not having the proper papers as a U.S. citizen.

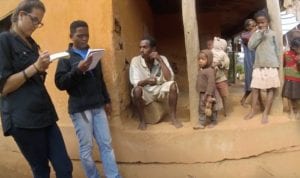

Dedicated to writing about the conditions in the Anglophone regions of Cameroon, Nganang said he was in the country for two weeks interviewing people. He said those in the western and English-speaking region of Cameroon must adhere to a 6 p.m. curfew, and the border to Nigeria is locked. He feels as a writer it’s his job to travel to the country and let people know what is going on there.

He said he always understood he might be arrested one day, “because of the kind of work I do. I’m very critical, I’m outspoken, I write editorials, etc. I’ve expressed my opinions freely for 20, 30 years. So I have always been prepared to face justice at a certain point because Cameroon is obviously a tyranny.”

According to a statement from a spokesperson for U.S. Rep. Lee Zeldin (R-Shirley), the congressman’s office had been in contact with the U.S. Department of State, Nganang’s family and Stony Brook University administrators during the professor’s detainment.

“In the face of an increasingly oppressive government, Professor Nganang has worked tirelessly for a better future for his country and family,” Zeldin said. “As Professor Nganang fights for the freedom of all Cameroonians, we fought for his. I look forward to his safe return home to his loved ones and the Stony Brook University community.”

Nganang is on leave from the university this academic year to attend to family business in Zimbabwe and to pursue a fellowship at Princeton University in the spring. During Nganang’s detainment, through a U.S. embassy representative, he sent a message to Harvey asking him to let his former students know that he hadn’t forgotten about their letters of recommendation.

Nganang said when he arrived at the airport in Washington D.C., he was greeted by a crowd of people, and he was given a ride home to Hopewell, New Jersey. The professor said he was grateful for the help he received from elected officials and representatives of the U. S. Embassy, and the support of his family, friends and neighbors. When he arrived home, he found friends at his house shoveling the driveway and filling his refrigerator.

“Coming out of jail after four weeks of a harsh ordeal and facing such an outpouring of love — my phone hasn’t stopped ringing since then because all my neighbors are concerned — guess what, it made a difference,” Nganang said.

Updated to include quotes from Patrice Nganang Jan. 4.