Since its invention as a diagnostic tool in the early 1970s, MRI has touched the lives of many patients, helping doctors to diagnose innumerable diseases and injuries, but Selden resident Sharyn Lauterbur-DiGeronimo remembers it as a connection to her late father.

She recalls one day finding baby clams as a 9 year old in Setauket Harbor, and holding them up to her dad, Paul Lauterbur. They were perfect for what he needed to create the first two-dimensional image using nuclear magnetic resonance. The scientist’s daughter said she has a connection to MRI, feeling that she had influenced her father’s desire to find a way to diagnose without causing harm to a patient.

“My dad used to have two lab rats, one I called Notch because he had a notch in one ear,” Lauterbur-DiGeronimo said. “I thought they were pets. One day Notch wasn’t there, and my dad had to explain what happened. They cut him open because he was a research rat. I completely freaked out, and I said there’s got to be a way to see inside without having to do that. I think that disturbed him a great deal.”

On Sept. 5, Stony Brook University Hospital remembered and gave back to the Lauterbur family by hosting a ceremony in the upcoming hospital Medical and Research Translation Building. The hospital and co-sponsor, the Long Island branch of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, presented a bronze plaque to be displayed inside the MART building commemorating the first 2-D NMR image. The university and IEEE also surprised the Lauterbur family by announcing they would be renaming the road leading up to the MART building Lauterbur Drive.

Lauterbur, who worked as a chemistry professor at SBU, is also known as the father of MRI. The story goes that the late professor was munching on a hamburger in a Pennsylvania restaurant when he had a “eureka” moment. In his mind’s eye, he saw a way to use his research in nuclear magnetic resonance to display objects in multidimensional detail. He rushed out of the restaurant and wrote the idea into a spiral notebook.

“Quite simply, the MRI is one of the most important medical discoveries of the 20th century,” said Dr. Samuel L. Stanley Jr., university president. “Lauterbur’s transformative work truly changed the course of modern medicine and trajectory of Stony Brook University.”

“You knew [Lauterbur] was doing an experiment because the lights would dim, the floor would shake, and the electrical bill was too high.”

— Tim Duong

Lauterbur published his ideas and the first example of a 2-D scan in the science journal, Nature, in 1973. In 2003 he was the co-recipient of a Nobel Prize for his work in nuclear magnetic resonance which led to the creation of MRI as a diagnostic tool before he passed away in 2007.

“MRI changed medical diagnostics around the world, and all that began right here at Stony Brook,” Tom Coughlin, the president-elect at IEEE-USA said.

Many who work with MRI technology said they owe their careers to Lauterbur.

“You knew [Lauterbur] was doing an experiment because the lights would dim, the floor would shake, and the electrical bill was too high,” said Tim Duong, director of MRI research at the hospital.

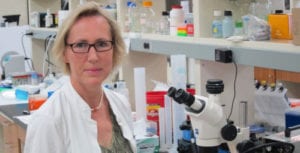

The half-sister of Lauterbur-DiGeronimo, Elise Lauterbur, 33, is a doctoral candidate in Stony Brook’s Ecology & Evolution Department and is working on her dissertation on the biochemistry and physiology of mammalian cyanide adaptation, particularly with Madagascar lemurs. She said it took years growing up before she truly understood what her father’s work had meant to the world.

“When I went with him when he was getting awards, I had people coming up to me saying, ‘Oh, your dad saved my sister’s life,’ or ‘Your dad is the reason I can still type on a computer,’” she said. “When my dad finally won the Nobel Prize it sunk in that his work had changed people’s lives in ways most scientists never manage.”

It would take years of tests for Lauterbur’s theories to turn into the prolific MRI machine, but the technology has improved immeasurably since then. Lauterbur-DiGeronimo said her father would appreciate that.

“When they were doing tests with it I’d spend like four hours in one, with a break for two hours in between sessions,” Lauterbur-DiGeronimo said. “The MRI I had last week took about 15 minutes.”

The new MART building, which is scheduled to open in 2019, will be used for cancer biology research, clinical research, biomedical informatics and imaging, according to dean of the School of Medicine, Dr. Kenneth Kaushansky.