SBU trio named to ocean acidification task force

Stony Brook University will be well represented on the new state Ocean Acidification Task Force examining the effect of acidification on New York’s coastal waters. The legislation was drafted by Assemblyman Steve Englebright (D-Setauket), chair of the Assembly Standing Committee on Environmental Conservation.

The university has three representatives on a 14-member team that will explore the impacts of acidification on the ecology, economy and recreational health of the coastal waters, while also looking to identify contributing factors and make recommendations to mitigate the effects of these factors.

“We have some of the best people in ocean acidification science who will be part of the process.”

— James Gennaro

Englebright said he was pleased to have the SBU representatives on the task force.

“We have these extraordinary scholars and researchers at the university who have a lot to contribute, and I hope that we’re able to listen closely to their advice regarding new policy and potentially new law to protect our coastal ecosystem and marine water.”

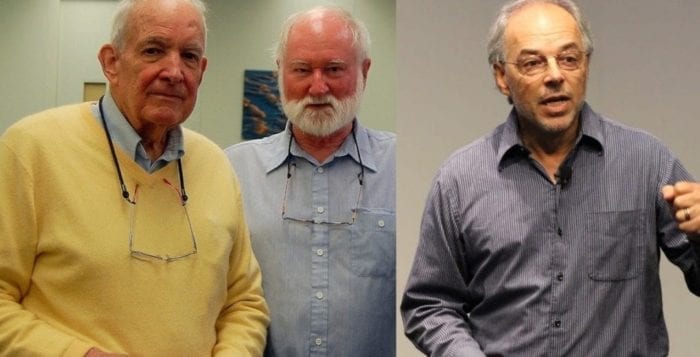

Larry Swanson, associate dean of the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences will join Malcolm Bowman, distinguished service professor and Carl Safina, endowed research chair for nature and humanity, both also from SoMAS. The task force, which will have its first meeting some time in September at SBU, was signed into law in 2016 and is operating under the direction of Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) and the New York State

Department of Environmental Conservation.

“We will make recommendations to the Department of Environmental Conservation and the Legislature and will share information about what our understanding of the state of knowledge of ocean acidification is, what are the impacts that we know about in New York state waters,” Swanson said, adding the group will suggest factors to monitor for consequences of acidification.

The composition of the group reflects its wide-ranging mandate, with members including Karen Rivara, owner of Aeros Cultured Oyster Company and former president of the Long Island Farm Bureau.

“We have a very significant shellfish industry that’s potentially in jeopardy. We need to understand what ocean acidification is doing to that industry.”

— Larry Swanson

Ocean acidification has been increasing at a rapid pace amid the increasing output of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide. Since the industrial revolution more than 200 years ago, ocean acidification has increased by about 30 percent, as absorbed carbon dioxide is converted into carbonic acid. The rate of change of ocean acidification is at a historic high and is 10 times faster than the last major acidification, 55 million years ago, according to a press release announcing the formation of the task force.

The task force, which will allow the public to provide input through a website it is developing and at its meetings, will focus on gathering existing data about the waters in and around Long Island, collecting additional information and offering the New York State Legislature suggestions for future policies.

The group will “figure out how to make science into policy-ready proposals,” said James Gennaro, chair of the task force and deputy commissioner at the DEC. Gennaro is pleased with the composition of the group.

“We have some of the best people in ocean acidification science who will be part of the process,” Gennaro said.

Swanson believes it’s important to consider understanding what is going on in the interior bays, including the Great South Bay and the Long Island Sound, as well as the New York Bight which is a curved area from Long Island to the north and east, and includes areas south and west to Cape May, New Jersey.

Some of the questions Swanson said he believes the group will explore include, “Can we measure changes based on what we know from historical information, how bad are those changes and what are the likely consequences?”

“This is very much a local water, coastal water, embayment improvement initiative.”

— James Gennaro

Improving the ecology of the ocean doesn’t have to be at the expense of the local economy, and vice versa, Swanson suggested.

Indeed, New York’s marine resources support nearly 350,000 jobs and generate billions of dollars through tourism, fishing and other business.

“We have a very significant shellfish industry that’s potentially in jeopardy,” Swanson said. “We need to understand what ocean acidification is doing to that industry. We can do things like control effluent going into the Great South Bay and Peconic Bay.”

Protecting and preserving the environment will “have a payoff” for the economy, Swanson added.

While the problem is global, monitoring agencies should oversee local impacts, Swanson and Gennaro agreed.

“This is very much a local water, coastal water, embayment improvement initiative,” Gennaro said, who added he is “eager” to get started.

The task force will meet no less than four times. The public will be able to follow the task force on the website that SBU and the DEC

are creating.

It is “imperative to do all we can to make sure we stay ahead of [and] act on” ocean acidification, Gennaro said.

Swanson suggested that local action can have consequences. People sometimes suggest that whatever policymakers do in New York will be a drop in the bucket compared to the overall problem of ocean acidification.

“If that’s the drop that causes the bucket to overflow, that’s an important drop,” Swanson said. “We can certainly make suggestions that we ought to do things on a national and global level.”