By Daniel Dunaief

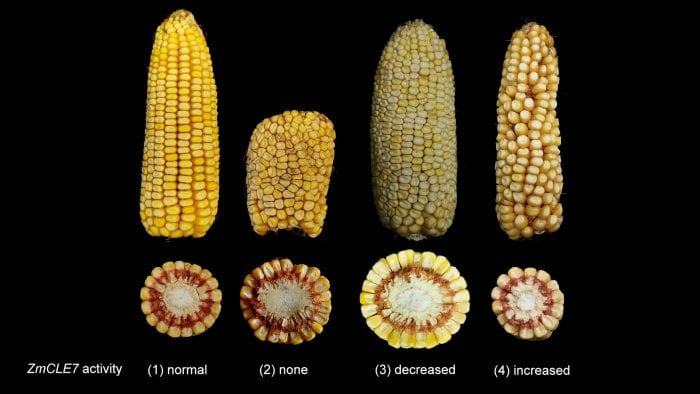

The current signal works, but not as well as it might. No signal makes everything worse. Something in the middle, with a weak signal, is just right.

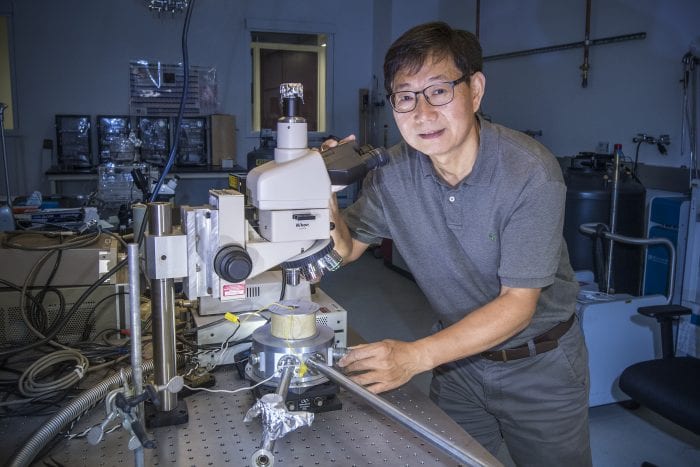

By using the gene-editing tool CRISPR, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Professor Dave Jackson has fine-tuned a developmental signal for maize, or corn, producing ears that have 15 to 26 percent more kernels.

Working with postdoctoral fellow Lei Liu in his lab, and Madelaine Bartlett, who is an Associate Professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Jackson and his collaborators published their work earlier this week in the prestigious journal Nature Plants.

Jackson calls the ideal weakening of the CLE7 gene in the maize genome the “Goldilocks spot.” He also created a null allele (a nonfunctional variant of a gene caused by a genetic mutation) of a newly identified, partially redundant compensating CLE gene.

Indeed, the CLE7 gene is involved in a process that slows the growth of stem cells, which, in development, are cells that can become any type of cell. Jackson also mutated another CLE gene, CLE1E5.

Several members of the plant community praised the work, suggesting that it could lead to important advances with corn and other crops and might provide the kind of agricultural and technological tools that, down the road, reduce food shortages, particularly in developing nations.

“This paper provides the first example of using CRISPR to alter promoters in cereal crops,” Cristobal Uauy, Professor and Group Leader at the John Innes Centre in the United Kingdom, explained in an email. “The research is really fascinating and will be very impactful.”

While using CRISPR (whose co-creators won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in October) has worked with tomatoes, the fact that it is possible and successful in cereal “means that it opens a new approach for the crops that provide over 60% of the world’s calories,” Uauy continued.

Uauy said he is following a similar approach in wheat, although for different target genes.

Recognizing the need to provide a subtle tweaking of the genes involved in the growth of corn that enabled this result, Uauy explained that the variation in these crops does not come from an on/off switch or a black and white trait, but rather from a gradient.

In Jackson’s research, turning off the CLE7 gene reduced the size of the cob and the overall amount of corn. Similarly, increasing the activity of that gene also reduced the yield. By lowering the gene’s activity, Jackson and his colleagues generated more kernels that were less rounded, narrower and deeper.

Uauy said that the plant genetics community will likely be intrigued by the methods, the biology uncovered and the possibility to use this approach to improve yield in cereals.

“I expect many researchers and breeders will be excited to read this paper,” he wrote.

In potentially extending this approach to other desirable characteristics, Uauy cautioned that multiple genes control traits such as drought, flood or disease resistance, which would mean that changes in the promoter of a few genes would likely improve these other traits.

“This approach will definitely have a huge role to play going forward, but it is important to state that some traits will still remain difficult to improve,” Uauy explained.

Jackson believes gene editing has considerable agricultural potential.

“The prospect of using CRISPR to improve agriculture will be a revolution,” Jackson said.

Other scientists recognized the benefits of fine-tuning gene expression.

“The most used type/ thought of mutation is deletion and therefore applied for gene knockout,” Kate Creasey Krainer, president and founder of Grow More Foundation, explained in an email. “Gene modulation is not what you expect.”

While Jackson said he was pleased with the results this time, he plans to continue to refine this technique, looking for smaller regions in the promoters of this gene as well as in other genes.

“The approach we used so far is a little like a hammer,” Jackson said. “We hope to go in with more of a scalpel to mutate specific regions of the promoters.”

Creasey Krainer, whose foundation hopes to develop capacity-building scientific resources in developing countries, believes this approach could save decades in creating viable crops to enhance food yield.

She wrote that this is “amazing and could be the green revolution for orphan staple crops.”

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration is currently debating whether to classify food as a genetically modified organism, or GMO, if a food producer used CRISPR to alter one or more of its ingredients, rather than using genes from other species to enhance a particular trait.

To be sure, the corn Jackson used as a part of his research isn’t the same line as the elite breeding stock that the major agricultural businesses use to produce food and feedstock. In fact, the varieties they used were a part of breeding programs 20 or more years ago. It’s unclear what effect, if any, such gene editing changes might have on those crops, which companies have maximized for yield.

Nonetheless, as a proof of concept, the research Jackson’s team conducted will open the door to additional scientific efforts and, down the road, to agricultural opportunities.

“There will undoubtedly be equivalent regions which can be engineered in a whole set of crops,” Uauy wrote. “We are pursuing other genes using this methodology and are very excited by the prospect it holds to improve crop yields across diverse environments.”