By Daniel Dunaief

When he was young, Simon Birrer asked his parents for a telescope because he wanted to look at objects on mountains and hills.

While he was passionate about science and good at math, Birrer didn’t know at the time he’d set his sights much further away than nearby hills or mountains in his professional career.

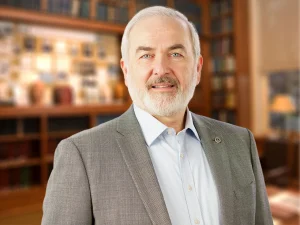

An Assistant Professor in the department of Astronomy and Physics at Stony Brook University, Birrer uses telescopes that generate data from much further away than nearby hills as he studies the way light from distant galaxies bends through a process called gravitational lensing. He also works to refine a measure of the expansion of the universe.

“All matter (including stars in galaxies) are causing the bending of light,” Birrer explained in an email. “From our images, we can infer that a significant fraction of the lensing has to come from dark (or more accurately: transparent) matter.”

Dark matter describes how a substance of matter that does not interact with any known matter component through a collision or pressure or absorption of light is transparent.

While they can’t see this matter through various types of telescopes, cosmologists like Birrer know it’s there because when it gets massive enough, it creates what Albert Einstein predicted in his theory of relativity, altering spacetime. Dark matter is effectively interacting with visible matter only gravitationally.

Every massive object causes a gravitational effect, Birrer suggested.

When a single concentration of matter occurs, the light of a distant galaxy can produce numerous images of the same object.

Scientists take several approaches to delens the data. They rely on computers to perform ray-tracing simulations to compare predictions with the astronomical images.

The degree of lensing is proportional to the mass of total matter.

Birrer uses statistics and helps draw conclusions about the fundamental nature of the dark matter that alters the trajectory of light as it travels towards Earth.

He conducts simulations and compares a range of data collected from NASA Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope.

Hubble constant

Beyond gravitational lensing, Birrer also studies and refines the Hubble constant, which describes the expansion rate of the universe. This constant that was first measured by Edwin Hubble in 1929.

“An accurate and precise measurement of the Hubble constant will provide us empirical guidance to questions and answers about the fundamental composition and nature of the universe,” Birrer explained.

During his postdoctoral research at UCLA, Birrer helped develop a new “formalism to measure the expansion history of the universe accounting for all the uncertainty,” Tomasso Treu, a Vice Chair for Astronomy at UCLA and Birrer’s postdoctoral advisor. “These methodological breakthroughs lay the foundation for the work that is being done today to find out what is dark matter and what is dark energy,” which is a force that causes the universe to expand at an accelerating rate.

Treu, who described Birrer as “truly outstanding” and one of the ‘best postdocs I have ever interacted with” in his 25-year career, suggested that his former student was relentless even after impressive work.

Soon after completing a measurement of the constant to two percent precision, Birrer started thinking of a “way to redo the experiment using much weaker theoretical assumptions,” Treu wrote in an email. “This was a very brave thing to do, as the dust had not settled yet on the first measurement and he questioned everything.”

The new approach required considerable effort, patience and dedication.

Birrer was “motivated uniquely by his intellectual honesty and rigor,” Treu added. “He wanted to know the answer and he wanted to know if it was robust to this new approach.”

Indeed, researchers are still executing this new measurement, which means that Treu and others don’t know how the next chapter in this search. This approach will, however, lead to greater confidence in whatever figure they find.

Larger collaborations

Birrer is a part of numerous collaborations that involve scientists from Europe, Asia, and Middle and South America.

He contributes to the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST). A planned 10-year survey of the southern sky, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is under construction in northern Chile.

The Simonyi Survey Telescope (SST) at the observatory will survey half the sky every three nights. It will provide a movie of that part of the sky for a decade.

The telescope and camera are expected to produce over 5.2 million exposures in a decade. In fewer than two months, a smaller commissioning camera will start collecting the first light. The main camera will start collecting images within a year, while researchers anticipate gathering scientific data in late next year or early in 2026.

The LSST is expected to find more strong gravitational lensing events, and in particular strongly lensed supernovae, than any prior survey.

Birrer is the co-chair of the LSST Strong Lensing Science Collaboration and serves on the Collaboration Council of the LSST Dark Energy Science Collaboration.

Birrer is also a part of the Dark Energy Survey, which was a predecessor to LSST. Researchers completed data taking a few years ago and are analyzing that information.

From mountains to the island

Born and raised in Lucerne, Switzerland, Birrer, who speaks German and the Swiss dialect, French and English, found physics and sociology appealing when he was younger.

“I was interested in how the world works,” he said.

While attending college at ETH Zurich in Switzerland, he became eager to address the numerous unknown questions in cosmology and astrology.

“How little we know about” these fields “dragged me in that direction,” said Birrer.

An avid skier, mountaineer and soccer player, Birrer bikes the five miles back and forth to work from Port Jefferson.

In addition to adding a talented scientist, Stony Brook also brought on board an effective educator.

Birrer is “knowledgeable and caring, patient and at the same time, he knows how to challenge people to achieve their best,” Treu explained. “I am sure he will be a wonderful addition to the faculty and he will play a leading role in training the next generation of scientists.”

In terms of the advice he found particularly helpful in his career, Birrer suggested he needed a nudge to combine his passion for theory with the growing trove of available data. His PhD advisor told him to “touch the data,” he said. The data keeps him humble and provides a reality check.

The friction between thought and data “leads to progress,” Birrer added. “You never know whether the thoughts are ahead of the experiments (data) or whether the experiments are ahead of the thoughts.”