By Jeffrey Sanzel

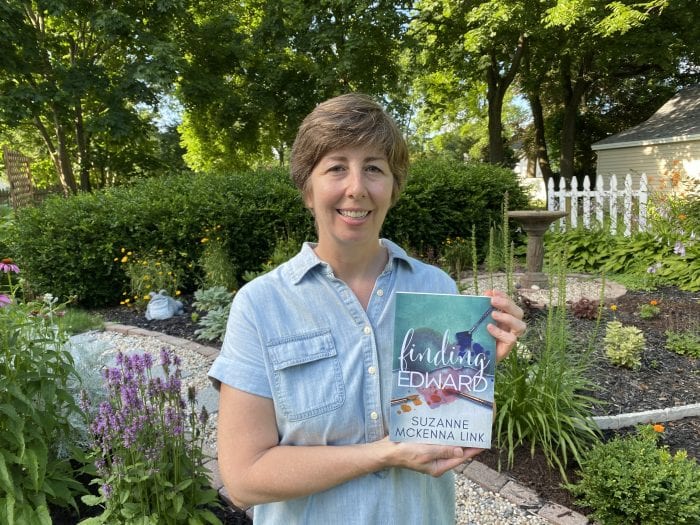

Looking for a life-affirming summer romance? Finding Edward, Suzanne McKenna Link’s third novel in her Save Me Series, is a first-rate diversion.

The stand-alone story follows Eddie Ruddack, a Long Island boy of twenty-six, in a time of challenge and transition. The novel opens with him reluctantly leaving his family home. His brother, Ray, is moving in with his fiancée, so Eddie is going to live with his boss, Toby, his pregnant wife, Claire, and their two daughters. And while he lives in the basement, it is clear he is a welcomed addition to the household.

Toby is a benevolent and involved employer; Claire is the ideal confidant and surrogate mother; both are things that Eddie desperately needs. In the meantime, Eddie, Ray, and their mother are awaiting news of the maternal grandmother’s will and their shared inheritance.

Eddie is a nice “getting-by” guy in search of answers but isn’t sure of the questions. And while he claims to want the perfect relationship (i.e., family, children), he just hasn’t found himself. He’s not so much a slacker as he is floater, much due to a spotty and inconsistent upbringing. His interests are clothes and art, without ever committing to a passion or landing on who he is or what he wants to be.

Even when taking a look at his room for the last time, there is a sense of disconnect: “A trash bag of dried up dreams filled with old tubes of paint, brittle paintbrushes, sketchbooks with yellowed pages, and several near-finished canvases. Bulky with squared edges that threatened to poke through the plastic, the bag was heavier than all the others. I dropped it off at the curb for waste pickup.”

His beloved grandmother’s bequeathal brings forward some life-altering truths, the most important of which is that Tom Ruddack, the father who walked out his family years before, is actually not Eddie’s biological father. His mother had a brief affair with a man named Giovanni Lo Duca, an Italian who was on a short-term work visa.

According to his grandmother’s wishes, Eddie needs to travel to Positano, on the Amalfi Coast. After the trip, he will receive money that she hopes will go towards tuition for art school, the interest that had bonded them in his childhood.

Eddie departs bruised — both figuratively and literally: the former from the news of his unknown paternity, the latter courtesy of her mother’s boyfriend, Mike. He arrives feeling “like a randomly placed pushpin on a wall map.” Immediately, the situation becomes fraught with problems, including the loss of his wallet with his debit card.

His disastrous first day in this idyllic setting is an excellent juxtaposition of a contradictory adventure. However, a chance act of bravery in the hotel lobby makes him a local hero, changing the course of his visit.

Through this he earns first the respect and then the friendship of the beautiful doctor, Ivayla, and ends up as her guest, staying in the house she shares with her two fathers, the gregarious Mario and the taciturn, reclusive, but gifted artist, Paolo. Ivayla becomes his guide as well as the object of his ardor. Their growing attraction fuels the book’s more personal and eventually intimate moments.

The book is full of rich detail, painting a vibrant Italian countryside, along with celebrating its people, its culture, and, of course, its food. Link is an engaging storyteller and shows us this magical foreign country through Eddie’s eyes. The descriptions reflect Eddie’s artistic bent and enhance the sense of a potentially bright and welcoming new world.

“Sun-bleached pastel houses, in gold, peach, white, and red, stacked high like a seawall. Precariously perched, they appeared ready to tumble into the sea at any moment. I imagined the people who lived in such a vertically challenged geography would be mentally tenacious and squat, physical powerhouses.” It is this artistic whimsy through which Link gives us a glimpse of Eddie’s creative potential.

Eddie experiences a reluctant but powerful awakening. He realizes that prior to Italy he had been living but not alive. “If I’d been home, I probably would have been in my basement apartment on the computer. I was here in an Italian city sharing wine and olives on a warm sunny evening with a local man and a mature, beautiful woman. Heightened by the foreign sights, sounds, and smells, my senses were becoming acutely discriminating, picking up scents and flavors I hadn’t known I was capable of.”

Ultimately, art and love become deeply intertwined. Eddie needs both to take the next step in his growth. The tale comes to a satisfying conclusion: Scritto nelle stelle … “It is written in the stars.” It is the incomplete Eddie who leaves for Italy but it is the maturing Edward who returns home. Finding Edward is a charming journey with just enough Italian sun to warm the heart.

A resident of Sayville, Suzanne McKenna Link (suzannemckennalink.com) is also the author of Saving Toby and Keeping Claudia. Pick up a copy of Finding Edward at bookrevue.com, Amazon.com or BarnesandNoble.com.

At the center of the story is Camp Hero.

At the center of the story is Camp Hero.

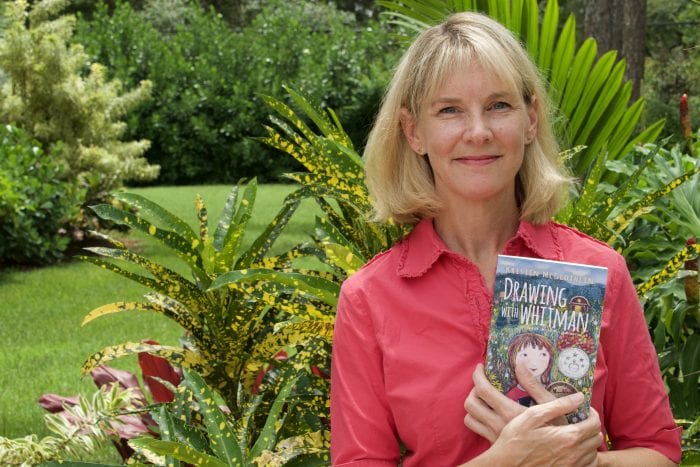

Who is the illustrator and how did you find her?

Who is the illustrator and how did you find her?

The Lubinskis remain with Izzy and Faye as the girls grow up. Aron has actively chosen not to reveal his nor Edyta’s history to the girls.

The Lubinskis remain with Izzy and Faye as the girls grow up. Aron has actively chosen not to reveal his nor Edyta’s history to the girls.

Why did you decide to write a middle- grade novel?

Why did you decide to write a middle- grade novel?

This begins the dark heart of the book. Moskowitz is not the businessman he claims but, instead, a procurer. (Another nod towards Aleichem, this time his short story The Man from Buenos Aires.)

This begins the dark heart of the book. Moskowitz is not the businessman he claims but, instead, a procurer. (Another nod towards Aleichem, this time his short story The Man from Buenos Aires.)

Safina divides the book into the study of sperm whales (families); scarlet macaws (beauty); and chimpanzees (peace). Each of the three sections is rich, detailed and engaging enough to be a book onto itself. He has brought them together under the umbrella of his exploration of culture.

Safina divides the book into the study of sperm whales (families); scarlet macaws (beauty); and chimpanzees (peace). Each of the three sections is rich, detailed and engaging enough to be a book onto itself. He has brought them together under the umbrella of his exploration of culture.

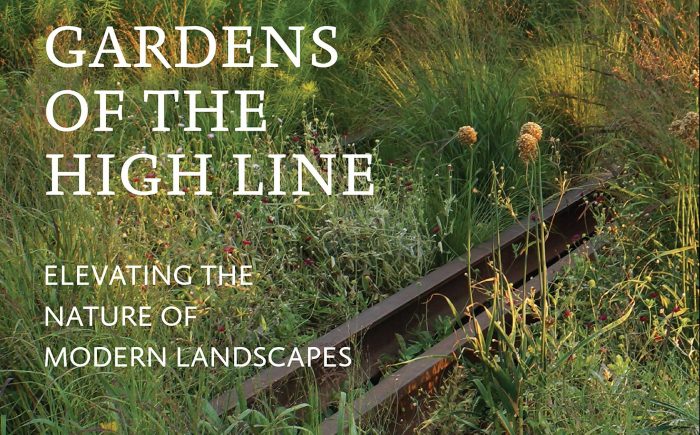

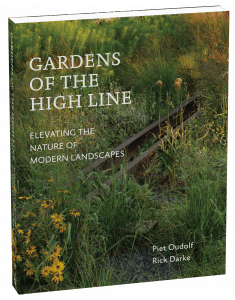

“Though it’s unlikely there will ever be another place quite like the High Line, it offers a wealth of insights and approaches worthy of emulation in gardens large or small, public or private. Authentic in spirit and execution, the High Line’s gardens offer a journey that is intriguing, unpredictable, imperfect, and, above all, transformative.”

“Though it’s unlikely there will ever be another place quite like the High Line, it offers a wealth of insights and approaches worthy of emulation in gardens large or small, public or private. Authentic in spirit and execution, the High Line’s gardens offer a journey that is intriguing, unpredictable, imperfect, and, above all, transformative.”