By John L. Turner

Walking out to get the morning paper the other day I noticed a small flock of robins land in a large American Holly growing in a corner of the front yard. They had landed to get their breakfast — an abundance of bright red holly berries scattered in bunches throughout the tree that will fuel them through part of the 40 degree day.

American Holly (Ilex opaca) is the most well-known member of the holly family on Long Island and one of our more distinctive native trees. Its leaves are unique, rigid with spines (to prevent browsing), and their dark green color gives rise to the Latin species name of opaca. Their flowers are whitish-green and are as inconspicuous as the berries are conspicuous. The attractive, tannish smooth-skin bark has distinctive “eyes,” locations where branches once grew. This is the tree — with its attractive contrasting colors of red and green — that’s seasonally associated with our holiday season.

If you pay closer attention, you’ll soon realize that not all American Hollies display bright red berries. Some trees have an abundance of berries while many others have none at all. The former are female trees and the latter male trees. All hollies are dioecious, meaning they have either male or female flowers but not both on the same tree.

This trait is fairly uncommon in the plant world (your garden asparagus is another example); more common are monoecious trees of which oaks, hickories, and maples are a few examples, in which a tree possesses both female and male flowers. And to complicate things a bit further: among plant species such as in the Rose family you have what are known as “perfect” flowers in which male parts (stamens) and female parts (pistils and ovaries) not only occur on the same plant but on the same flower.

American Holly is widely distributed on Long Island and you can see scattered trees in many forest tracts but two places standout if you want to see a forest dominated by hollies: the maritime holly forest situated in the Sunken Forest at Fire Island National Seashore and the forests on the north side of the road in Montauk State Park (quite viewable along the trail that takes you out to the viewing blind overlooking the popular seal haul-out site located in the northwestern corner of the park). In the Sunken Forest, the unique forest that grows between the holly co-dominates the forest with shadbush and sassafras. It is a very rare type of forest known from very few locations, being ranked by the New York Natural Heritage Program as both an S1 and G1 community, in the state and world, respectively. Another fine example of a maritime holly forest is a two hour ride from western Long Island: the holly forests at Sandy Hook, New Jersey.

American Holly has long been prized for its berries and foliage and there are accounts in older botanical books rueing the wanton cutting of holly foliage during the holiday season. One author remarks he was glad that the holly wasn’t often cut down, although its wood is hard and can be easily stained or shellacked, “since the depredations of the Christmas-green pickers take toll enough.”

Inkberry (Ilex glabra), an attractive shrub that grows throughout Long Island, is a member of the holly family; it is especially abundant in low-lying areas in the Pine Barrens such as long streams and pond edges. An extensive stand of Inkberry is found along the Paumanok Path as it passes just north of Owl Pond in the Birch Creek/Owl Pond section of the Pine Barrens located in Southampton.

Inkberry is a classic “coastal plain” species and, not surprisingly, its distribution in New York State is restricted to Long Island. Inkberry prefers sand soils where the water table is shallow, i.e., not far below the surface. It is not typically found growing in standing water but right alongside wet areas where the roots can easily access moisture. The species name refers to the glabrous or very smooth nature of the attractive green foliage of the plant — hairy it is not! The common name refers, of course, to the dark blue berries that stain your fingers an inky-purple if you crush them.

The winterberries from the third group of holly members on Long Island and unlike the prior two groups are not evergreen, dropping their leaves each autumn. But they are holly members, nevertheless, as can be seen by a glance at their bright red berries. Smooth Winterberry (Ilex laevigata) and Common Winterberry (Ilex verticillata) are the two more common species; Mountain Holly (Ilex mucronata) and Mountain Winterberry (Ilex montana) also occur here.

Back to the robins on a late November day: as their feeding demonstrated, while not edible to humans (in fact, they are poisonous to humans and their pets), birds, including the beautiful cedar waxwing, readily eat the brightly advertised holly fruits, especially later in the winter season when other more highly-preferred berries (read: higher fat content) have disappeared. Thus, hollies play a helpful role in keeping nature’s cafeteria open through the tough stretch of late winter through early spring, helping to sustain songbird flocks overwintering on Long Island.

A resident of Setauket, author John Turner is conservation chair of the Four Harbors Audubon Society, author of “Exploring the Other Island: A Seasonal Nature Guide to Long Island” and president of Alula Birding & Natural History Tours.

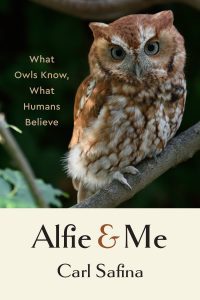

The Eastern Screech Owl (Megascops asio) is one of two common woodland owls that find breeding habitat here on Long Island. Along with their much larger cousin, and sometimes mortal enemy the Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus), Screech Owls are surprisingly common in forests both large and small. Even parcels as small as ten acres are likely to host a breeding pair. Less common woodland owls here include Saw-whet (Aegolius acadicus) and Long-eared Owls (Asio otis) “whoo” are joined by open country visitors during the winter months — Snowy Owls (Bubo scandiacus) and Short-eared Owls (Asio flammeus), coastal and grassland inhabitants respectively.

The Eastern Screech Owl (Megascops asio) is one of two common woodland owls that find breeding habitat here on Long Island. Along with their much larger cousin, and sometimes mortal enemy the Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus), Screech Owls are surprisingly common in forests both large and small. Even parcels as small as ten acres are likely to host a breeding pair. Less common woodland owls here include Saw-whet (Aegolius acadicus) and Long-eared Owls (Asio otis) “whoo” are joined by open country visitors during the winter months — Snowy Owls (Bubo scandiacus) and Short-eared Owls (Asio flammeus), coastal and grassland inhabitants respectively.

While the main office for Long Island Repair Café (they have a Facebook page) is at 1424 Straight Path in Wyandanch, run by Starflower Experiences, an environmental educational organization, volunteers host repair cafés throughout Long Island. The main office can be reached at (516) 938-6152.

While the main office for Long Island Repair Café (they have a Facebook page) is at 1424 Straight Path in Wyandanch, run by Starflower Experiences, an environmental educational organization, volunteers host repair cafés throughout Long Island. The main office can be reached at (516) 938-6152.

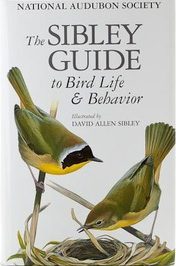

Another book that has a slightly different format but is richly informative is The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behavior (numerous authors). It, too, discusses the unique qualities of different bird families but before the family discussion has five chapters that delve into great detail about Flight, Form, and Function; Origins, Evolution, and Classification; Behavior; Habitats and Distributions; and Populations and Conservation. If I were able to recommend only one book for your nightstand to increase the breadth and depth of your knowledge about birds it would be this book.

Another book that has a slightly different format but is richly informative is The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behavior (numerous authors). It, too, discusses the unique qualities of different bird families but before the family discussion has five chapters that delve into great detail about Flight, Form, and Function; Origins, Evolution, and Classification; Behavior; Habitats and Distributions; and Populations and Conservation. If I were able to recommend only one book for your nightstand to increase the breadth and depth of your knowledge about birds it would be this book.