By Jeffrey Sanzel

In 1939, T.S. Eliot published a slender volume of poetry: Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. Fast-forward just over 40 years and Andrew Lloyd Weber’s megahit Cats premiered in the West End, where it played for 8,949 performances, becoming the longest-running West End musical, a record it held until 2006. The Broadway production opened in 1982 and ran for 7,845 performances; it is now the fourth longest-running Broadway show. Cats went on to be seen internationally, playing in dozens of countries and languages.

In 1998, a direct-to-video production was shot at London’s Adelphi Theatre. While significant cuts were made and it was played on a new set, it gives a sense of the stage production.

Cats has always been a divisive musical, dividing into two distinct camps: It has its champions and its detractors, with few in the middle ground.

The current offering of Cats many lives is the film directed by Tom Hooper with a screenplay by Hooper and Lee Hall. This means that Hooper is doubly responsible for what is on the screen. And while Hooper’s work has included the John Adams miniseries, The King’s Speech and The Danish Girl, Hooper also gave us the clumsy, bloated and wholly unsatisfying 2012 Les Misérables.

The plot of Cats — such as it is — tells of the Jellicle Ball, an annual gathering of cats where one is granted the chance to go the Heavyside Layer and rewarded with a new life. Here, it is told through the eyes of Victoria, an abandoned kitten. All of this is just a structure in which to introduce a range of cats who each pitch their right to be granted this wish, their individuality displayed through a series of musical turns. Throughout, the candidates are thwarted by the mysterious Macavity, whose nefarious plan is made clear fairly early on.

The film opens strongly with one of the best numbers from the show,“Jellicle Cats.” It manages to provide cinematic spectacle without losing its musical theater roots. Ultimately, it was when Hooper allows Broadway to come through, the movie finds its limited success. When the cast dances, there are moments of real celebration. Unfortunately, after the first 10 minutes or so, he decided to not trust the material, and the film becomes choppy, disconnected and feels overlong. There is an unnecessary slapstick, singing rats and dancing cockroaches. These elements are neither whimsical nor clever and enhance neither story nor spectacle.

The film boasts a number of high profile names. Rebel Wilson as Jennnyanydots and James Cordern as Bustopher Jones are ill-served by aggressively abrasive choices — novelty songs that are stripped of their charm and turned grotesque. Idris Elba fairs decently as the ominous Macavity, and Taylor Swift, as his henchperson, Bombalurina, is not given much to do but her one decently executed number.

Judi Dench, as feline matriarch Old Deuteronomy, and Ian McKellen, as Gus the Theatre Cat, are channeling everything they’ve done for the past five decades and come out best. Jennifer Hudson, as the downtrodden Grizabella, is too overwrought and loses the sympathetic core of “Memory.” Newcomer Francesca Hayward functions nicely as Victoria the catalyst for the action (no pun intended).

What is most surprising is that the voices in general are pleasant but not strong, which is an odd choice for an almost sung-through film. (The less said about the dialogue that has been shoe-horned in, the better.)

However, the biggest problem — and it is insurmountable — is the overall visual of the film. The characters have been strangely CGI-ed, and they come across neither as humans or cats but as some Island of Dr. Moreau hybrids. There is an unfinished quality to the faces, as if they are poking their heads through a Coney Island cut-out. The bodies are clearly feline but some are clothed and some are not, sending a bizarre and uncomfortable mixed message.

There is no commitment to what the audience is supposed to be seeing and the result is disturbing. Why the creators did not take a page from the stage production is a mystery for at least then they could have found an aesthetically pleasing or least unifying design.

There has been discussion of a Cats film since the musical first became popular. Given the nature of the source, it is a challenging one. And while the play will continue to prowl stages across the world, the film will surely be a strange and unpleasant footnote in the history of movie musicals.

Rated PG, Cats is now playing in local theaters.

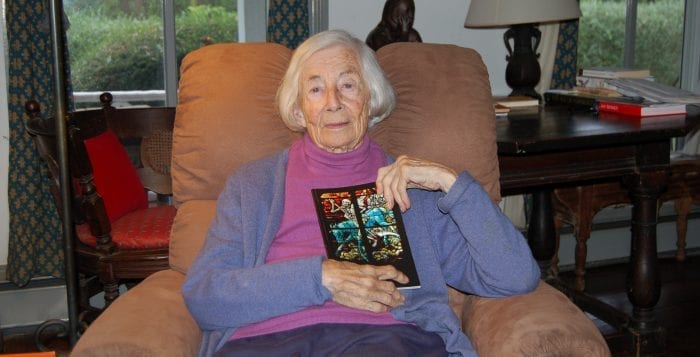

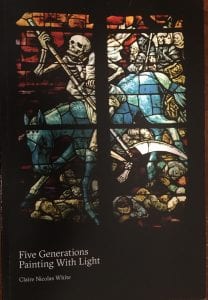

Throughout, White paints a clear picture of her family, plentiful in detail and event. She manages to evoke their personalities in quick, vivid strokes. The descriptions are colorful and entertaining, revealing the highs and lows, the conflicts and the triumphs.

Throughout, White paints a clear picture of her family, plentiful in detail and event. She manages to evoke their personalities in quick, vivid strokes. The descriptions are colorful and entertaining, revealing the highs and lows, the conflicts and the triumphs.

Growing up in Luton, England, Javed lives in a world plagued by racism, both small and large. Incidents involving the neo-Nazi National Front as well as the damage of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s economic polices are very much present in his day-to-day life. Javed, who began keeping a diary at age 10, writes poetry as well as lyrics. His dreams are kept at bay by his very traditional father, Malik (Kulvinder Ghir). Early in the film, Malik loses his factory job, sending the family into a financial tailspin. His hope is that Javed will go into a real profession — doctor, lawyer, accountant —

Growing up in Luton, England, Javed lives in a world plagued by racism, both small and large. Incidents involving the neo-Nazi National Front as well as the damage of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s economic polices are very much present in his day-to-day life. Javed, who began keeping a diary at age 10, writes poetry as well as lyrics. His dreams are kept at bay by his very traditional father, Malik (Kulvinder Ghir). Early in the film, Malik loses his factory job, sending the family into a financial tailspin. His hope is that Javed will go into a real profession — doctor, lawyer, accountant —

Now the book has been turned into a slightly rushed but not entirely ineffective feature film. Following the book’s plot closely, screenwriter Mark Bomback and director Simon Curtis honor the spirit and the structure if never quite capturing the underlying pulse. As with the novel, the story begins with the elderly Enzo and then goes back to Denny bringing Enzo home; Denny’s courtship of and marriage to Eve; the birth of their daughter, Zoe; Eve’s illness; and all that follows.

Now the book has been turned into a slightly rushed but not entirely ineffective feature film. Following the book’s plot closely, screenwriter Mark Bomback and director Simon Curtis honor the spirit and the structure if never quite capturing the underlying pulse. As with the novel, the story begins with the elderly Enzo and then goes back to Denny bringing Enzo home; Denny’s courtship of and marriage to Eve; the birth of their daughter, Zoe; Eve’s illness; and all that follows. Milo Ventimiglia (from TV’s This Is Us) makes a sensitive and charming Denny. While not an actor of great range, what he does, he does well. He captures Denny’s warmth and earnestness as well as his passion for racing. He is wholly believable, finding joy and pain in Denny’s achievements and struggles.

Milo Ventimiglia (from TV’s This Is Us) makes a sensitive and charming Denny. While not an actor of great range, what he does, he does well. He captures Denny’s warmth and earnestness as well as his passion for racing. He is wholly believable, finding joy and pain in Denny’s achievements and struggles. And, second, Kevin Costner’s flawless voicing of Enzo is what ultimately pulls tautest on the heartstrings. Costner’s soothing rumble is the true soundtrack and one that will resonate long after the movie is over.

And, second, Kevin Costner’s flawless voicing of Enzo is what ultimately pulls tautest on the heartstrings. Costner’s soothing rumble is the true soundtrack and one that will resonate long after the movie is over.