Reviewed By Jeffrey Sanzel

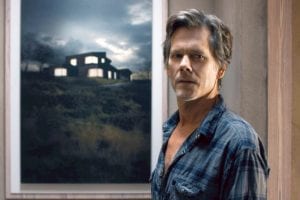

Kevin Bacon is no stranger to horror films. In his varied career, he has previously appeared in seven, from the original Friday the Thirteenth (1980) right through The Darkness (2016). Now he stars in You Should Have Left, a film of some style but very little substance.

The psychological thriller, written and directed by David Koepp, is based on Daniel Kehlmann’s slender 2017 German novella, Du Hättest Gehen Sollen. It is unsurprisingly produced by Blumhouse, which recently has provided a mixed bag of the genre, ranging from the first-rate Get Out to the head-scratchingly terrible Fantasy Island.

You Should Have Left opens with a nightmare within a nightmare within a nightmare. One image becomes very important later in the film’s sole interesting reveal. But it is not enough to sustain the one and a half hours that bridge the gap.

The story is simple. Kevin Bacons plays former banker Theo Conroy, the older husband of the young and beautiful Susanna (Amanda Seyfried) and even older father of the precociously inquisitive Ella (Avery Essex).

Susanna is a successful film and stage actress married to the brooding Theo — but it is hard to see why. (Cue Theo’s fits of jealousy, followed by half-hearted apologies. Statements like “I don’t trust because you’re a really good actress” followed by “I guess I shouldn’t have said that.” It’s not real strong on the dialogue front.)

Hints about Theo’s unsavory past are dropped throughout the first leg of this limping journey. Eventually, it is divulged that he was accused and acquitted of murdering his first wife by letting her drown in the bathtub. (Cue lots of overflowing bathtub images, both with and without corpse.) However, the publicity forced him into an early retirement.

The family takes a remote house in a Welsh village, prior to Susanna’s next gig in London. (Cue odd villagers making cryptic statements.) They rent it online from a mysterious landlord with whom they never actually speak; Theo and Susanna later discover that they thought the other had rented it. (Cue Scooby Doo: “Ruh roh!”)

The house is spacious and modern and rather blank; it is also off-kilter, with walls at strange angles, and an inside bigger than the outside. (Cue hallways and doors that lead to different hallways and other doors that open and close and lead back to rooms that couldn’t be there but are but … cue lots of running up and down stairs.) There are no pictures but plenty of wall switches. (Cue lamps that turn on by themselves and light peeking from underneath doors.)

There are some genuinely unsettling moments: A trail of Polaroids is wonderfully ominous; a shadow without a source flits across a wall; a figure appears in the window as they attempt to escape; Theo’s complete awareness that he is having a nightmare and tries to unsuccessfully slap himself awake — all standard but crafted moments that just don’t add up to anything more than … standard crafted moments. (Cue “Isn’t that just like … ?”)

About half way through, there is a nice bit with two cell phones that plays both into Theo’s paranoia and his reality. It motivates the latter part of the film which accelerates in tempo and yet never seems to pick up steam. Early on, it is teased that time is not quite in sync and this becomes a major point in the film’s finale. However, it needs a little more plot and a little less plod.

The performances are not bad. Kevin Bacon plays Theo as tightly-wound, introspective, and guilt-ridden. (Cue grimaces and ferocious journal writing and tossed pens.) Amanda Seyfried plays Susanna as both tolerant and vaguely narcissistic. (Cue long suffering looks alternating with exasperation.) Geoff Bell is the ominously knowing storekeeper, Angus. (Cue impenetrable accent.)

But the real star of the film is the house. A modern wonder or an eyesore, depending on point-of-view. Is it evil or does it draw evil to it to punish? Angus mutters some vague history that there’s always been a house on the land and it’s the Devil’s Tower. (Cue “What did he say and should I rewind to hear it or never mind this must almost be over, right?”)

There have been plenty of entertaining films that have dabbled in the dark powers of a house — Burnt Offerings and The Haunting, for example. This just isn’t one of them.

Ultimately, it is just another in a long line of generic arthouse wannabes. Where it fails as a horror movie, it also doesn’t succeed as a character study. To quote Gertrude Stein (Cue pretentious comparison): “There is no there there.”

When faced with a title like You Should Have Left, so many possibilities come to mind. You Should Have Left … and So Should I. You Should Have Left … and Taken Me With You. Or You Should Have Left … and That Would Have Been Right. (Cue bad pun.) But, probably the best title would have been You Shouldn’t Have Gone in the First Place.

Rated R, You Should Have Left is available On Demand.

The Lubinskis remain with Izzy and Faye as the girls grow up. Aron has actively chosen not to reveal his nor Edyta’s history to the girls.

The Lubinskis remain with Izzy and Faye as the girls grow up. Aron has actively chosen not to reveal his nor Edyta’s history to the girls.

This begins the dark heart of the book. Moskowitz is not the businessman he claims but, instead, a procurer. (Another nod towards Aleichem, this time his short story The Man from Buenos Aires.)

This begins the dark heart of the book. Moskowitz is not the businessman he claims but, instead, a procurer. (Another nod towards Aleichem, this time his short story The Man from Buenos Aires.)

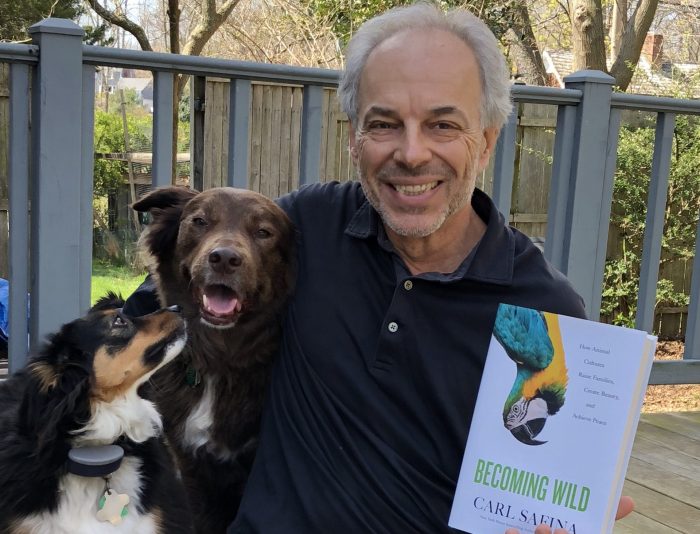

Safina divides the book into the study of sperm whales (families); scarlet macaws (beauty); and chimpanzees (peace). Each of the three sections is rich, detailed and engaging enough to be a book onto itself. He has brought them together under the umbrella of his exploration of culture.

Safina divides the book into the study of sperm whales (families); scarlet macaws (beauty); and chimpanzees (peace). Each of the three sections is rich, detailed and engaging enough to be a book onto itself. He has brought them together under the umbrella of his exploration of culture.