Family through the prism of stained glass

Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

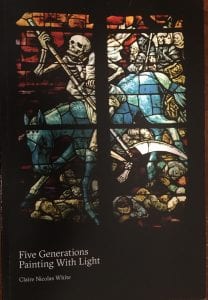

Claire Nicolas White shares her family’s journey in the art of stained glass in her very engaging Five Generations Painting With Light.

The book opens with a crisply written introduction followed by a succinct and informative history of stained glass. White’s eloquent prose defines her connection in a sharp parallel to the compositions that are to be explored: “Mine is a strange inheritance, transparent, ablaze with light in all colors, breakable, but precious.”

The history details the materials, construction and sites of the pieces as well as the fact that the creation of stained glass today is much the same as it was over a thousand years ago. The nobility as well as the dangers of the trade are also touched upon. The intersection of necessity, art, folklore and fantasy are at its heart. It should be remembered that the windows often served as a method of ecclesiastical communication, telling biblical stories and imparting scriptural themes.

From there, White traces her family history, beginning with her Dutch great-grandfather, artist François Nicolas. His son Charles Nicolas then focused on the business aspects and managing the Nicolas glass studio. White’s father, Joep Nicolas, first rebelled from the family business, but, after studying philosophy and art history, he found that “painting with light remained irresistible.” Joep married Suzanne, an artist with similar if complementary tastes. Joep was highly successful and his work could be seen not just in churches but in assorted businesses and educational institutions, — “square miles of glass.”

White and her sister, Sylvia, were born in northern Holland but, with the advent of Hitler, Joep moved his family to the United States. It was here that White and Sylvia learned their father’s skill: “I won’t leave you a fortune, but I will have taught you a profession.” Sylvia continued in the work while White found a career as a writer and art critic, publishing everything from poetry to fiction to biography. After leaving the world of graphic design, Sylvia’s son, Diego Semprun Nicolas, took up the family mantle, completing the five generations.

Throughout, White paints a clear picture of her family, plentiful in detail and event. She manages to evoke their personalities in quick, vivid strokes. The descriptions are colorful and entertaining, revealing the highs and lows, the conflicts and the triumphs.

Throughout, White paints a clear picture of her family, plentiful in detail and event. She manages to evoke their personalities in quick, vivid strokes. The descriptions are colorful and entertaining, revealing the highs and lows, the conflicts and the triumphs.

In addition, White has wonderful insight into the history of art and the artistic temperament. She discusses her father’s seeing his work in musical terms, a strong and vivid metaphor. She quotes her sister’s approach to art as a whole: “Glass is great … but I need to tell tales, religious tales, but also legends, myths. The iconography is inspiring. Life is like a tapestry. You’re influenced by what you’re exposed to and use what you need.”

The book is beautifully enhanced by the many photos of stained glass. It is a delight to see the evolution of the artists through their works and from generation to generation. As Joep stated: “Whoever has been given the spirit, the will, the talent, let him tackle this art form; glass is a willing substance that God had not for nothing allowed us to discover.” Claire Nicolas White has given us an absorbing glimpse into this world of unusual masterpieces.

Claire Nicolas White is an acclaimed American poet, novelist and translator of Dutch literature. She is the granddaughter-in-law of architect Stanford White. Her sister, Sylvia Nicolas, designed and installed all the stained glass in Sts. Philip and James R.C. Church in St. James.

Meet the author at a Master Class at the Ward Melville Heritage Organization’s Educational & Cultural Center, 97P Main St., Stony Brook as she discusses her latest book, ‘Five Generations Painting with Light’ on Oct. 23 from 1 to 2:30 p.m. The event is free and refreshments will be served. Call 631-689-5888 to reserve a spot.

Growing up in Luton, England, Javed lives in a world plagued by racism, both small and large. Incidents involving the neo-Nazi National Front as well as the damage of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s economic polices are very much present in his day-to-day life. Javed, who began keeping a diary at age 10, writes poetry as well as lyrics. His dreams are kept at bay by his very traditional father, Malik (Kulvinder Ghir). Early in the film, Malik loses his factory job, sending the family into a financial tailspin. His hope is that Javed will go into a real profession — doctor, lawyer, accountant —

Growing up in Luton, England, Javed lives in a world plagued by racism, both small and large. Incidents involving the neo-Nazi National Front as well as the damage of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s economic polices are very much present in his day-to-day life. Javed, who began keeping a diary at age 10, writes poetry as well as lyrics. His dreams are kept at bay by his very traditional father, Malik (Kulvinder Ghir). Early in the film, Malik loses his factory job, sending the family into a financial tailspin. His hope is that Javed will go into a real profession — doctor, lawyer, accountant —

Now the book has been turned into a slightly rushed but not entirely ineffective feature film. Following the book’s plot closely, screenwriter Mark Bomback and director Simon Curtis honor the spirit and the structure if never quite capturing the underlying pulse. As with the novel, the story begins with the elderly Enzo and then goes back to Denny bringing Enzo home; Denny’s courtship of and marriage to Eve; the birth of their daughter, Zoe; Eve’s illness; and all that follows.

Now the book has been turned into a slightly rushed but not entirely ineffective feature film. Following the book’s plot closely, screenwriter Mark Bomback and director Simon Curtis honor the spirit and the structure if never quite capturing the underlying pulse. As with the novel, the story begins with the elderly Enzo and then goes back to Denny bringing Enzo home; Denny’s courtship of and marriage to Eve; the birth of their daughter, Zoe; Eve’s illness; and all that follows. Milo Ventimiglia (from TV’s This Is Us) makes a sensitive and charming Denny. While not an actor of great range, what he does, he does well. He captures Denny’s warmth and earnestness as well as his passion for racing. He is wholly believable, finding joy and pain in Denny’s achievements and struggles.

Milo Ventimiglia (from TV’s This Is Us) makes a sensitive and charming Denny. While not an actor of great range, what he does, he does well. He captures Denny’s warmth and earnestness as well as his passion for racing. He is wholly believable, finding joy and pain in Denny’s achievements and struggles. And, second, Kevin Costner’s flawless voicing of Enzo is what ultimately pulls tautest on the heartstrings. Costner’s soothing rumble is the true soundtrack and one that will resonate long after the movie is over.

And, second, Kevin Costner’s flawless voicing of Enzo is what ultimately pulls tautest on the heartstrings. Costner’s soothing rumble is the true soundtrack and one that will resonate long after the movie is over.

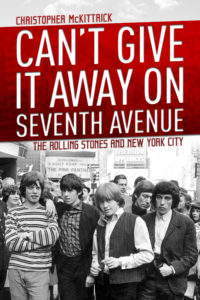

![Cant Give it Away_cover_v2.3[1]](https://tbrnewsmedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Cant-Give-it-Away_cover_v2.31-e1564167504488-700x357.jpg)

The book picks up with the band when it is first establishing itself. We are treated to the intrigue, the late night clubs, the relationships and marriages, the celebrities (everyone from Andy Warhol to Bill Clinton), hotel destructions and, of course, the drugs. The Rolling Stones are almost a history of the changing drug use and drug culture in the 20th century. Wild parties, addictions, police raids and arrests, stints in rehab and recovery were a never-ending cycle.

The book picks up with the band when it is first establishing itself. We are treated to the intrigue, the late night clubs, the relationships and marriages, the celebrities (everyone from Andy Warhol to Bill Clinton), hotel destructions and, of course, the drugs. The Rolling Stones are almost a history of the changing drug use and drug culture in the 20th century. Wild parties, addictions, police raids and arrests, stints in rehab and recovery were a never-ending cycle.