By Jeffrey Sanzel

On Sunday, April 25, the 93rd Academy Awards will be held at the Dolby Theatre at the Hollywood & Highland Center. The show will air live on ABC beginning at 8 p.m. Producer Steven Soderbergh has promised this year’s presentation to be completely different. With no live audience, COVID restrictions, and a host of other challenges, he promises an experience like no other Oscars. Okay. Sure. Whatever. But it still comes down to who wins and who loses.

Whether you’ve seen one or most or (the unicorn of movie-watching) all of the nominees, you have an opinion. Often, it’s the negative: “I can’t believe [insert title/actor/director/costume designer here] was nominated! That was the worst [movie/acting/direction/costume design].” “Did you see it?” you will ask. “Well, no. But I heard it was …”

Heated discussions, office pools, gatherings, and myriad Facebook posts consume the battleground. And, of course, everything comes down to personal taste. (I have a weakness for large manor houses where they iron the newspapers. Thank you, Downton Abbey.) Here is a very personal assessment. And while I don’t know if it will find agreement, hopefully there won’t be too much gnashing of teeth.

It is a tight race for Best Actor in a Leading Role, with five worthy candidates. Riz Ahmed has one of those visceral roles as a drummer losing his hearing in Sound of Metal. On the opposite end of the spectrum is Steven Yeun’s young father in Minari; it is a small, quiet performance of deep nuance with a delicate mix of pain and hope in every moment. Anthony Hopkins hits all the right notes as a contrasting patriarch in The Father. Hopkins presents a devastating look at the torments of dementia. While there are glimpses of kindness — particularly in the final moments — it is a colder performance. Gary Oldman is exceptional in all he does; he is a true chameleon. But he won in 2018 for his Winston Churchill. Screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz in Mank, working on Citizen Kane, while engaging, doesn’t compare in gravitas. Chadwick Boseman’s musician Levee in Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom was extraordinary, building up to one of the finest performed monologues in cinematic history. The award — sadly posthumous — is his — and rightfully so.

Best Actress in a Leading Role offers a range of possibilities. Viola Davis is mesmerizing as Ma Rainey; her performance is jaw-dropping in scope, fire, and nuance, and she is almost unrecognizable. That makes for a winning combination. What might cancel out Davis is Andra Day’s competing performance as another musical icon in The United States vs. Billie Holiday. Both Vanessa Kirby and Frances McDormand (always a favorite) give powerful performances that dominated their films — Pieces of a Woman and Nomadland, respectively. Carey Mulligan — also seen giving a completely different performance in The Dig — is both harrowing and enigmatic in her portrait of revenge in Promising Young Woman; while not the kind of role that usually attracts high-profile awards, she could challenge Davis. But McDormand is still in the running with her multi-dimensional turn. This category is truly anyone’s game.

Equally hard to predict is Best Actor in a Supporting Role. While voters love a comedic actor in a serious role, Sacha Baron Cohen (The Trial of the Chicago 7) is the least likely to win. As Sound of Metal didn’t get the viewers, this would also put Paul Raci at the back of the pack. With the remaining three — Daniel Kaluuya and LaKeith Stanfield in Judas and the Black Messiah and Leslie Odom, Jr. in One Night in Miami — it is Kaluuya as Black Panther leader Fred Hampton who will most likely take the trophy. There is always the possibility of a split vote with Stanfield, which could move Odom, Jr. or even Raci’s Viet Nam vet to the front.

As for the Best Actress in a Supporting Role nominees, Amanda Seyfried brings a hint of complexity to Mank’s Marion Davies, but it gets lost in the overall clutter of the film. And while Maria Bakalova has garnered accolades for Borat 2, the movie has divided audiences. Olivia Colman is beautifully measured as the daughter in The Father and, in another season, might have won. The oft-nominated Glenn Close does some of her best work in Hillbilly Elegy; like Oldman, she is unrecognizable. However, the film itself had so much political backlash that unfortunately makes a win very unlikely. I predict Youn Yuh-jung is going to receive the Oscar. Her grandmother in Minari is a wealth of surprises, eschews every expectation, and is the film’s heartbeat.

I am reluctant to pick a winner for Best Director as I have always felt the award is tied to the Best Picture (or perhaps should be). Unlikely are Thomas Vinterberg for Another Round and David Fincher for Mank. Lee Isaac Chung’s work might be too subtle in Minari, lacking in grand strokes. Emerald Fennell has done an exceptional job shaping Promising Young Woman, but I think the award will go to Chloé Zhao for the heartfelt guidance she has given to Nomadland.

Of the eight nominees for Best Picture, The Father is least likely to win. While memorable, its stage roots show. Sound of Metal has not gotten the traction that it needs to move up in the ranks. Mank is probably too much of an insider’s look into the film business. Promising Young Woman’s black comedy edge may be too much for much of its audience. The Trial of the Chicago 7 and Judas and the Black Messiah overlap in their portrayal of a time of political turmoil and intersect with portrayals of the murdered Black Panther Hampton. They are both historical and yet very timely, with the latter film being a stronger possibility. But it is the devastating, universal Nomadland (recipient of the Golden Globe for Best Drama) that will most likely take this year’s crown.

And that ends a very narrow, biased, wholly random assessment of a few of the upcoming Academy Award categories. Time — and Sunday night — will tell.

(Oh, and while there are some very fine works nominated for Best Animated Feature, my money is completely on Soul.)

Each will speak differently to the individual viewer. On a personal level, these moments demand attention:

Each will speak differently to the individual viewer. On a personal level, these moments demand attention:

While the family has come for a new start, the marriage shows signs of deep trouble. There are disagreements about where to live and how to spend their money; they don’t fully agree on dealing with their son’s heart murmur. They live in a cold distance, with anger always brewing under the brittle surface. Moments of affection are severed by the movement of a hand, the turning of a head, or the shrugging of a shoulder. The children’s stress reflects their parents’ inability to communicate. Soon-ja observes, “You two will fight over anything.” The daughter, Anne (Noel Kate Cho, mature beyond her years), is more parent than child, running interference and caring for her younger brother, David (Alan Kim, real, honest, and very funny).

While the family has come for a new start, the marriage shows signs of deep trouble. There are disagreements about where to live and how to spend their money; they don’t fully agree on dealing with their son’s heart murmur. They live in a cold distance, with anger always brewing under the brittle surface. Moments of affection are severed by the movement of a hand, the turning of a head, or the shrugging of a shoulder. The children’s stress reflects their parents’ inability to communicate. Soon-ja observes, “You two will fight over anything.” The daughter, Anne (Noel Kate Cho, mature beyond her years), is more parent than child, running interference and caring for her younger brother, David (Alan Kim, real, honest, and very funny).

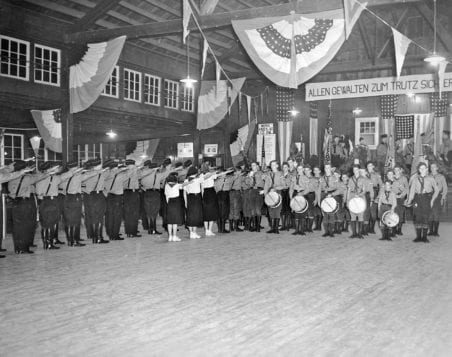

Much of the book covers the shift that came with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The attack spurred civilian involvement along with unification behind the war effort. He documents the early failures and gradual shift to competency in air raid drills across the Island. This example also emphasizes the growing cooperation between the military and non-military populations.

Much of the book covers the shift that came with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The attack spurred civilian involvement along with unification behind the war effort. He documents the early failures and gradual shift to competency in air raid drills across the Island. This example also emphasizes the growing cooperation between the military and non-military populations.

In addition to his wide-eyed and well-intentioned if slightly oblivious royal, Murphy and co-star Arsenio Hall each played another three supporting roles. The film was funny, raunchy, and a huge hit. While critical response was mixed, it was a financial success. Coming to America was Paramount’s highest-earning film and the third-highest-grossing film in United States box office. Its worldwide total is estimated as high as $350 million. (It is Eddie Murphy’s eighth highest-grossing film.)

In addition to his wide-eyed and well-intentioned if slightly oblivious royal, Murphy and co-star Arsenio Hall each played another three supporting roles. The film was funny, raunchy, and a huge hit. While critical response was mixed, it was a financial success. Coming to America was Paramount’s highest-earning film and the third-highest-grossing film in United States box office. Its worldwide total is estimated as high as $350 million. (It is Eddie Murphy’s eighth highest-grossing film.) Meanwhile, Zamunda faces a threat from its militaristic neighbor Nextdoria, ruled by dictator General Izzi (Wesley Snipes). Izzi is the older brother of Imani (Vanessa Bell Calloway), who Akeem jilted in the first film. Upon discovery that Akeem has a successor, the General wants Lavelle to marry his daughter Bopoto (Teyana Taylor). All of this frustrates Akeem’s capable eldest daughter, Princess Meeka (KiKi Layne), who aspires to run the kingdom. While being trained as a prince, Lavelle falls in love with his no-nonsense royal groomer Mirembe (Nomzamo Mbatha).

Meanwhile, Zamunda faces a threat from its militaristic neighbor Nextdoria, ruled by dictator General Izzi (Wesley Snipes). Izzi is the older brother of Imani (Vanessa Bell Calloway), who Akeem jilted in the first film. Upon discovery that Akeem has a successor, the General wants Lavelle to marry his daughter Bopoto (Teyana Taylor). All of this frustrates Akeem’s capable eldest daughter, Princess Meeka (KiKi Layne), who aspires to run the kingdom. While being trained as a prince, Lavelle falls in love with his no-nonsense royal groomer Mirembe (Nomzamo Mbatha). The movie has a few strong moments. One of the best scenes involves a job interview. Lavelle comes into direct conflict with white privilege, embodied by Mr. Duke (Colin Jost). The scene is genuinely funny—Lavelle uses his “white voice” to attempt to secure a position for which he is qualified but under-educated. The encounter reflects Lavelle’s day-to-day challenges. It helps that Fowler has an easy charm and is genuinely likable. His strut is a thin mask for a good young man who wants to grow into a better adult. He never severs his connection to his Queens roots but is open to what Zamunda has to offer. Fowler owns his hero’s journey.

The movie has a few strong moments. One of the best scenes involves a job interview. Lavelle comes into direct conflict with white privilege, embodied by Mr. Duke (Colin Jost). The scene is genuinely funny—Lavelle uses his “white voice” to attempt to secure a position for which he is qualified but under-educated. The encounter reflects Lavelle’s day-to-day challenges. It helps that Fowler has an easy charm and is genuinely likable. His strut is a thin mask for a good young man who wants to grow into a better adult. He never severs his connection to his Queens roots but is open to what Zamunda has to offer. Fowler owns his hero’s journey. Both Jones and Morgan have the same material they’ve been given elsewhere but usually better crafted. As they have cornered the particular brand of humor, their laughs come easily but their sources are uninspired. In contrast, Layne and Mbatha play it straight and come out with dignity if no laughs.

Both Jones and Morgan have the same material they’ve been given elsewhere but usually better crafted. As they have cornered the particular brand of humor, their laughs come easily but their sources are uninspired. In contrast, Layne and Mbatha play it straight and come out with dignity if no laughs.