Reviewed by Jeffrey Sanzel

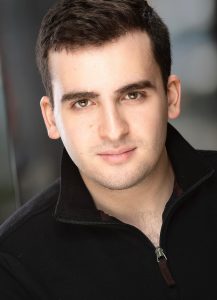

Matt Hoffman’s debut album, The Start of Something Big, featured jazz and pop standards including “When You’re Smiling,” “What Are you Doing the Rest of Your Life?,” “Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You,” and the title song. He celebrates these favorites with his own terrific take. Hoffman has an effortless tenor that both soars and charms. Dropping in May 2019, it has since garnered over one million cumulative streams on Spotify, YouTube, and Apple Music.

After receiving the Celebration Award from Michael Feinstein’s Songbook Academy Vocal Competition (held at the 3,500-seat Palladium Concert Hall), Hoffman performed with Feinstein at Manhattan’s 54 Below. He has sung at New York City’s Birdland, with The New York Voices’ Lauren Kinhan and Janis Siegel of the Manhattan Transfer. Hoffman made multiple appearances there for Jim Carouso’s “The Cast Party,” where the legendary Billy Stritch accompanied him. Additionally, he has been seen at New York’s Swing 46 as well as The Jazz Loft in Stony Brook.

Hoffman’s voice crosses many categories. His influences range from Harry Connick, Jr., to Frank Sinatra. Both contemporary and a throwback, he has a unique and vibrant sound. His blend of studio and theatre background splendidly colors his presentation, enhancing the beautiful vocals with a resonant emotional connection.

And now, Hoffman’s sophomore outing, Say It Ain’t Snow!, offers his personal flair on popular holiday fare. The seven tracks feature a wonderful range of material and boast a thrilling seventeen-piece Big Band with strings. The arrangements, by Trevor Motycka, are exceptional, perfectly matching Hoffman’s ability to shift from the grand to the witty to the heartfelt. There is the twinkle of holidays past—the spirit of the season of the great singers of television, vinyl, and CDs.

Say It Ain’t Snow! kicks off with an appealing, magnetic “This Christmas.” Hoffman’s knowing “It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas” winks to so many fireside holiday specials. The Christmas Classics medley—“Here Comes Santa Claus,” “Let It Snow,” “Winter Wonderland,” and “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town”—shows an exceptional variety with seamless segues and a particularly exciting rendition of “Let It Snow.”

The sense of discovery in “The Christmas Song” is unique and surprisingly introspective. “Silver Bells” readily zings from a pastoral stroll in the snow to the lights of the city, showing off his jazz chops with masterful scatting. The simplicity and honest clarity of “O, Holy Night” is the perfect contrast to his letting loose with the final song, an exuberant, wry, “Run, Rudolph, Run.” In every number, Hoffman doesn’t just sing—he paints a vocal picture that is rich, evocative, and inviting.

The sense of discovery in “The Christmas Song” is unique and surprisingly introspective. “Silver Bells” readily zings from a pastoral stroll in the snow to the lights of the city, showing off his jazz chops with masterful scatting. The simplicity and honest clarity of “O, Holy Night” is the perfect contrast to his letting loose with the final song, an exuberant, wry, “Run, Rudolph, Run.” In every number, Hoffman doesn’t just sing—he paints a vocal picture that is rich, evocative, and inviting.

Returning as album producer is Jackson Hoffman, who partnered with Hoffman on The Start of Something Big. Jackson Hoffman produced and co-wrote 2020 Voice winner Carter Rubin’s latest single. Here, he has assembled exceptional musicians to create the overall sonic landscape, coupling the Big Band sound with the neo-Swing era music arrangements.

There are not enough accolades for the band, which swings with bold brass playing magically against the lush strings. The ensemble creates the ideal backing for Hoffman. Hopefully, Hoffman and company will continue to offer seasonal treats as well as a wide range of jazz, classical, musical theatre, and standard catalogs.

No holiday season is complete without Christmas music. Whether you are a fan of traditional carols or lean towards the contemporary, music inspires holiday cheer. Hoffman’s Say It Ain’t Snow! has something for everyone, with its warmth, sense of wonder, and real joy. It is a gift for this, next, and all the Christmases to follow.

Say It Isn’t Snow! is available on music streaming platforms including Spotify, Apple Music, iTunes, Amazon Music and SoundCloud.

The book contains accounts of orbs of light, dark silhouettes, footsteps in the middle of the night, and slamming doors. There are rooms where the temperature is exceptionally and inexplicably cold. There are scents with no source. But it is not about things that go bump in the night (though many do, including the voice of a screaming woman). Instead, it is about the energy and the presence (perhaps more blessed than haunted). Most of the encounters are with benign and even welcoming entities. Whether focusing on a member of the Culper Spy Ring, a library custodian, a mother guilty of filicide, or victims of a shipwreck, Brosky shows respect for her mission.

The book contains accounts of orbs of light, dark silhouettes, footsteps in the middle of the night, and slamming doors. There are rooms where the temperature is exceptionally and inexplicably cold. There are scents with no source. But it is not about things that go bump in the night (though many do, including the voice of a screaming woman). Instead, it is about the energy and the presence (perhaps more blessed than haunted). Most of the encounters are with benign and even welcoming entities. Whether focusing on a member of the Culper Spy Ring, a library custodian, a mother guilty of filicide, or victims of a shipwreck, Brosky shows respect for her mission.