Movie Review: ‘The Last Blockbuster’ is a trip down memory lane

Reviewed (sort of) by Jeffrey Sanzel

You see, there’s this new movie — The Last Blockbuster — and it’s fun, you know (ya know)?

‘Cause, when you watch it, sure, you’re going to (gonna) watch it, but what you’re really going to (gonna — all right, I’ll stop now) do is remember. For a movie about a business that was only around for thirty-five years, it evokes a nostalgia for days-gone-by — for a kinder, gentler time before the world went to streaming-in-a-handbasket, and those crazy kids wouldn’t stay off your lawn. Or something like that.

But seriously. (Kinda …)

As the various celebrities you might have heard of (and a whole bunch of people you’ve never seen) share their thoughts about Blockbuster, you’ll exclaim, “Right! That’s it! That’s what I did! That’s exactly right!” (And, yes, every sentence you say or think is going to end with an exclamation point.)

As I watched The Last Blockbuster, written by Zeke Kamm and directed by Taylor Morden, I thought of my video watching history. I was twenty when I bought my first VCR — a Goldstar I believe. I had memberships at two mom-and-pop stores (one was actually just several shelves in a pharmacy) where the prices ranged from $1 to $2.

By the time I was in my early twenties, Blockbuster had replaced most small operations. I alternated between the two in Port Jefferson Station and the one in Rocky Point. It always the time/geography formula:

Let’s see, I’ll be coming from work, but I won’t be going back that way until Monday, so maybe if I swing by the one in Rocky Point before going home, that would make more sense. But, if I don’t rent any new releases, it would be just as easy to go to the one on Route 112, and I can return it when I’m on my way in to work on Monday.

It became the world’s least significant word problem. “If a man leaves the house at noon, on a Tuesday, with one movie due the following day, but two movies rented three days earlier at $2.99 …”

So … The Last Blockbuster.

The Last Blockbuster, ironically, is now streaming on Netflix. Ironic because services like Netflix, while not directly killing video stores, were one of the final nails in its plastic coffin. The documentary goes to certain lengths to explain that it was the financial meltdown of 2008 that caused Blockbuster’s true downward spiral. But there is no question that streaming services and VOD were detrimental to the traditional setup.

The movie begins by tracing the history of the business. It follows the rise and the decline of the video rental service, giving insight into the shift from the small operations through the Blockbuster takeover, and the corporate stores versus the franchises.

It points out that revenue sharing changed the entire face of the video industry. Blockbuster would sell movies to the stores at the lowest costs, and then they would take a percentage of the rental fee. It reduced the store owner’s costs from $100 a movie to a few dollars, enabling the purchase of multiple copies. As small video stores were incapable of competing, Blockbuster created a monopoly.

At one point, Netflix offered to sell to Blockbuster for a surprisingly low price tag. The film’s hypothetical reenactment depicts this with great whimsy: Muppet-like puppets around a board room table laugh a Netflix rabbit out of the room.

The movie takes some time to find its rhythm. The filmmakers were concerned that the company’s history would not be interesting enough to be presented linearly so they’ve interspersed it with individual remembrances, which muddies the progress. Once they are past that, it flows better.

The catalyst for the entire project is The Little Store That Could. At its peak, there were 9,000 Blockbuster stores. Supposedly, there was a time when one was opening every seventeen hours. When the filmmakers began, there were twelve remaining stores. Then there were four, with three of them in Alaska. And then there was one.

As of 2019, the last existing Blockbuster is in Bend, Oregon, managed by Sandi Harding, the Blockbuster Mother. Much of the film focuses on Sandi, following her around the store and in her home, interacting with customers and her family, and shopping for stock at Target.

Sandi is beloved, having employed dozens of young people in her community and many of her family members. She is charming, open, and honest. There is something truly noble about her desire to keep the store going — almost a mythic figure on a hero’s quest. We can’t help but root for her.

Throughout, she is waiting to hear from Dish, the monolith who bought the bankrupt Blockbuster. The film’s only suspense is whether they will allow her to renew for another five years. The Bend store has now become a place of pilgrimage. People come from all over the world to take pictures and buy souvenirs. It is a Grand Canyon of pop culture.

Various men in the video industry offer insight into the business side. Often, there is a sense that they are reluctant witnesses, tight-lipped and uncomfortable, weighing in on both the smart and less savvy choices made by the company, including the infamous eradication of late fees, costing the company two-thirds of its revenue. They make for a strong contrast with the others who are interviewed simply for their love of the place.

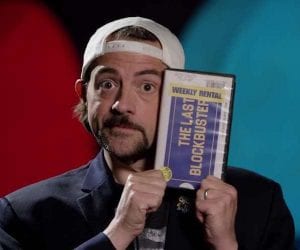

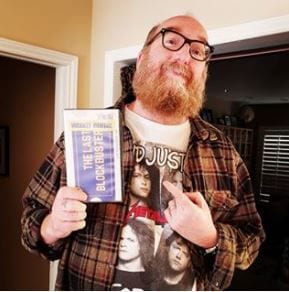

Writer-director Kevin Smith (Clerks) has only the fondest memories. Comedian Doug Benson is giddy when he finally visits Bend. Others singing the praises are actors Ione Skye, Brian Posehn, Paul Scheer, Samm Levine, and Jamie Kennedy.

Particularly entertaining are the random musings of Ron Funches, whose free-associating is one of the film’s quirkier delights. Some have direct connections to Blockbuster in their pasts, having worked in local outfits in their teen years; others simply reminisce.

As I watched, I realized that everyone was saying the same thing, which brought me to the realization that what The Last Blockbuster truly celebrates is the universal experience. We are all part of a collective memory because we all had the same experience:

It’s Friday night, and we enter the blue and yellow temple with our significant other or spouse or family or friends. Occasionally, we make a solo visit. We breathe in the smell of stale popcorn and slightly opened soda, the library aroma of media dust, and the unique scent of plastic cases. We walk the perimeter of new releases, looking at each one, staring at the covers, occasionally reading a blurb.

Oh, look, the one we wanted isn’t in. We go to the register and ask the clerk when it’s due back. It was due back today. So we stand at the counter and hope that it gets returned. After a bit, we roam the aisles, meandering into the older sections, neatly divided by genre. We make stacks of videos (and later DVDs). We negotiate: If we rent that for you, can we get this for me? Finally, we’re ready to check out. The clerk goes through each one to make sure that the tape matches the case. (Ah, the plastic VHS cases with their brick-like weight and satisfying click as they close with a perfect snap.)

Sometimes we spent more time looking for the movies than we did watching them.

That was the Blockbuster culture. And that was a great part of the joy. “Ah,” we think, “the youth of today will never know this as they scroll through their My List of a hundred movies and a thousand television shows.”

The Last Blockbuster is not a great documentary. For something that doesn’t even run a full ninety minutes, it is often repetitive. But it has an enormous heart and genuine nostalgia. It celebrates the last bastion of a bygone era. So, when you watch it, be kind. (And rewind.)

Photos courtesy of 1091 Pictures