The next piece of personal protective equipment that Suffolk County needs is gowns, as Long Island remains at the epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Today, the county will receive 25,000 gowns, thanks to the work of the procurement team which has been “scouring the planet for supplies,” County Executive Steve Bellone (D) said on his daily conference call with reporters.

While those gowns will help the health care workers who have been helping the influx of patients coming into hospitals, they won’t be sufficient amid the ongoing outbreak.

“The burn rate [for gowns] is absolutely incredible,” said Bellone, who urged residents to donate hospital gowns to the Fire, Rescue and Emergency Services site at 102 East Avenue in Yaphank between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m.

Bellone thanked Onandago County Executive Ryan McMahon, who is sending reinforcements in the form of 22 nurses to Stony Brook University.

“Those nurses will come down here to provide assistance and relief to front line workers who have been going at this nonstop, working shift after shift in an incredibly intense environment,” Bellonme said. “We are extraordinarily grateful.”

Bellone also thanked DS Services of America, a company based in Georgia, who brought a tractor trailer load of bottled water, coffee, tea and a collection of beverages to the county. The county will deliver those donations to first responders and health care workers.

Criminals Caught

While some people have taken the crisis in the county as an opportunity to contribute, others have seen it as a chance to commit crimes.

This week, the Suffolk County Police Department arrested Joseph Porter of Mastic Beach and Rebecca Wood of Lake Ronkonkoma in Bay Shore for a string of 11 burglaries committed between March 9, the day after Suffolk County had its first coronavirus patient, and April 7.

One of the alleged burglars told police he thought he would be able to get away with his crimes because the police were distracted with the virus.

“He was wrong,” Bellone said.

Additionally, police apprehended John Cayamanda, a St. James resident, whom they allege committed several acts of arson since the start of the virus.

“This is a reassurance to the public that our police department and all of our law enforcement agencies are on the job and are able to do their work,” Bellone said.

Suffolk County Police Commissioner Geraldine Hart said the number of domestic violence incidents, which have been climbing nationally amid social distancing and work-from-home arrangements, has climbed 8 percent.

“We have a dedicated unit for domestic violence and they are continuing their outreach, identifying individuals and making sure they get the assistance they need,” Hart said on the call.

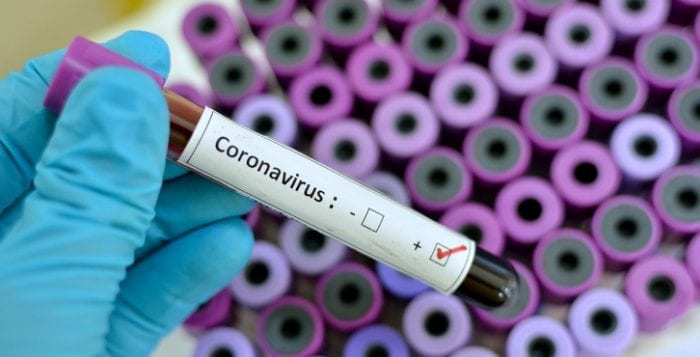

Cases Climb

As for the coronavirus tests, the number of confirmed cases continues to climb, rising 1,700 to 18,602 people. The total is about a half of the number reported for all of mainland China, Bellone said.

As of yesterday, the number of Suffolk County Police officers who tested positive for COVID-19 was 62, with 18 of those officers returning to work.

The number of people hospitalized in the last 24 hours showed the smallest increase in recent weeks, rising by 10 people.

“That is a good sign,” Bellone said.

The number of people entering the Intensive Care Unit, meanwhile, rose by 14 people, which is still below a recent high from several days ago.

Overall, the number of hospital beds in the county stands at 3,365, with 750 total ICU beds. Currently, there are 585 hospital beds and 102 ICU beds available.

Over the last 24 hours, 39 people have died from the virus, which brings the total for the county up to 362.

“Our hearts break for those families who have been impacted by this,” Bellone said. “We know we are not at the apex. We are still in the thick of this.”

To reach young people who may not be practicing the same social distancing guidelines, Bellone said he was launching a peer-to-peer Covid challenge. This initiative attempts to tap into the creativity of students to share their stories about what they are doing online and with their peers. He said he hopes those people who follow social distancing guidelines will inspire their peers to do the same.

Seeking Plasma Donors, Saving N95 Masks

Separately, Stony Brook University is looking for donors who have recovered from a coronavirus infection who can contribute plasma that might help others fight the disease.

Led by Elliott Bennet-Guerrero, the Medical Director of Perioperative Quality and Patient Safety, the study plans to treat up to 500 Long Island patients with convalescent plasma, which is rich in the antibodies patients who defeated COVID-19 used to return to health.

Stony Brook University Hospital received approval from the Food and Drug Administration to treat patients through a randomized, controlled study. In a typical study, the groups would be evenly divided between those who receive the treatment and those who get a control. The public health crisis, however, has allowed researchers to change that mix, so that 80 percent of the patients in the trial will receive the convalescent plasma.

Also, Stony Brook announced a novel way to disinfect the coveted N95 masks, which have become the gold standard to protect health care workers and first responders.

Ken Shroyer, the Chair of the Department of Pathology, and Glen Itzkowitz, Associate Dean for Research Facilities & Operations, found that masks passed fit tests after they were treated up to four repeated cycles in a dry heat oven at 212 degrees Fahrenheit for 30 minutes.

In an email, Shroyer explained that temperature control is important because the masks need to be sterilized at the highest temperature possible, although they failed if they were heated above 248 degrees Fahrenheit. Since some ovens might not have accurate thermostats, it would be helpful to confirm the temperature inside the oven with a thermometer.

The procedure involves placing each mask in a paper bag labeled with the name of the health care provider and work location. A technician seals the bags with indicator tape and places them in the oven.

“The team has discussed potential fabrication efforts to construct a sterilizer racking system capable of recycling as many as 8,000 masks a day through the heat treatment,” Itzkowitz said in a press release.

Stony Brook researchers hope hospitals, clinics, or nursing homes could use this technique to protect workers on the front lines of the battle against the virus.