By Daniel Dunaief

Ramana Davuluri feels like he’s returning home.

Davuluri first arrived in the United States from his native India in 1999, when he worked at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. After numerous other jobs throughout the United States, including as Assistant Professor at Ohio State University and Associate Professor and Director of Computational Biology at The Wistar Institute in Philadelphia, Davuluri has come back to Long Island.

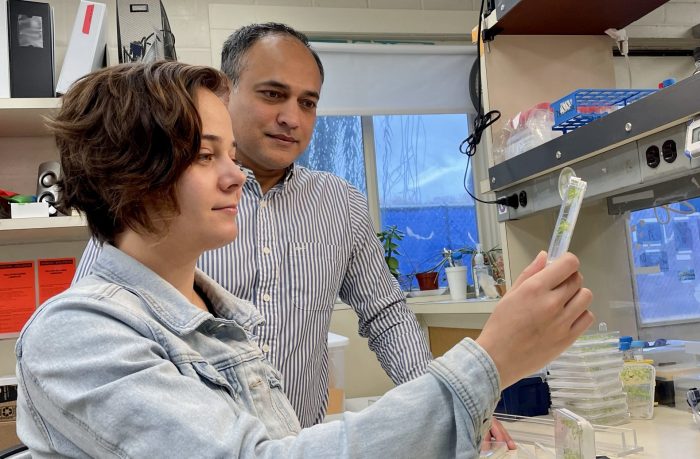

As of the fall of 2020, he became a Professor in the Department of Biomedical Informatics and Director of Bioinformatics Shared Resource at Stony Brook Cancer Center.

“After coming from India, this is where we landed and where we established our life. This feels like our home town,” said Davuluri, who purchased a home in East Setauket with his wife Lakshmi and their six-year-old daughter Roopavi.

Although Davuluri’s formal training in biology ended in high school, he has applied his foundations in statistics, computer programming and, more recently, the application of machine learning and deep algorithms to the problems of cancer data science, particularly for analyses of genomic and other molecular data.

Davuluri likens the process of the work he does to interpreting language based on the context and order in which the words appear.

The word “fly,” for example, could be a noun, as in an insect at a picnic, or a verb, as in to hop on an airplane and visit family for the first time in several years.

Interpreting the meaning of genetic sentences requires an understanding not only of the order of a genetic code, but also of the context in which that code builds the equivalent of molecular biological sentences.

A critical point for genetic sequences starts with a promoter, which is where genes become active. As it turns out, these areas have considerable variability, which affects the genetic information they produce.

“Most of the genetic variability we have so far observed in population-level genomic data is present near the promoter regions, with the highest density overlapping with the transcription start site,” he explained in an email.

Most of the work he does involves understanding the non-coding portion of genomes. The long-term goal is to understand the complex puzzle of gene-gene interactions at isoform levels, which means how the interactions change if one splice variant is replaced by another of the same gene.

“We are trying to prioritize variants by computational predictions so the experimentalists can focus on a few candidates rather than millions,” Davuluri added.

Most of Davuluri’s work depends on the novel application of machine learning. Recently, he has used deep learning methods on large volumes of data. A recent example includes building a classifier based on a set of transcripts’ expression to predict a subtype of brain cancer or ovarian cancer.

In his work on glioblastoma and high grade ovarian cancer subtyping, he has applied machine learning algorithms on isoform level gene expression data.

Davuluri hopes to turn his ability to interpret specific genetic coding regions into a better understanding not only of cancer, but also of the specific drugs researchers use to treat it.

He recently developed an informatics pipeline for evaluating the differences in interaction profiles between a drug and its target protein isoforms.

In research he recently published in Scientific Reports, he found that over three quarters of drugs either missed a potential target isoform or target other isoforms with varied expression in multiple normal tissues.

Research into drug discovery is often done “as if one gene is making one protein,” Davuluri said. He believes the biggest reason for the failure of early stage drug discovery resides in picking a candidate that is not specific enough.

Davuluri is trying to make an impact by searching more specifically for the type of protein or drug target, which could, prior to use in a clinical trial, enhance the specificity and effectiveness of any treatment.

Hiring Davuluri expands the bioinformatics department, in which Joel Saltz is chairman, as well as the overall cancer effort.

Davuluri had worked with Saltz years ago when both scientists conducted research at Ohio State University.

“I was impressed with him,” Saltz said. “I was delighted to hear that he was available and potentially interested. People who are senior and highly accomplished bioinfomaticians are rare and difficult to recruit.”

Saltz cited the “tremendous progress” Davuluri has made in the field of transcription factors and cancer.

Bioinformatic analysis generally doesn’t take into account the way genes can be interpreted in different ways in different kinds of cancer. Davuluri’s work, however, does, Saltz said.

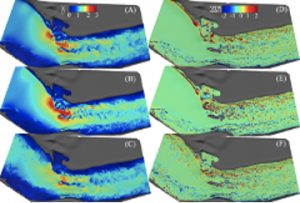

Developing ways to understand how tumors interact with non-tumor areas, how metastases develop, and how immune cells interact with a tumor can provide key advances in the field of cancer research, Saltz said. “If you can look at how this plays out over space and time, you can get more insights as to how a cancer develops and the different part of cancer that interact,” he said.

When he was younger, Davuluri dreamt of being a doctor. In 10th grade, he went on a field trip to a nearby teaching hospital, which changed his mind after watching a doctor perform surgery on a patient.

Later in college, he realized he was better in mathematics than many other subjects.

Davuluri and Lakshmi are thrilled to be raising their daughter, whose name is a combination of the words for “beautiful” and “brave” in their native Telugu.

As for Davuluri’s work, within the next year he would like to understand variants.

“Genetic variants can explain not only how we are different from one another, but also our susceptibility to complex diseases,” he explained. With increasing population level genomic data, he hopes to uncover variants in different ethnic groups that might provide better biomarkers.