By Daniel Dunaief

Time is not on our side.

That’s one of the messages, among others, from a recent paper in Frontiers in Marine Conservation that explored Marine Protected Areas around the United States.

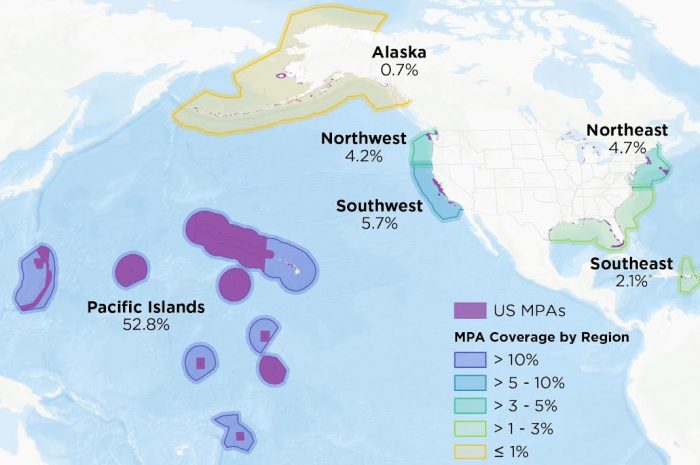

In a study involving scientists at universities across the country, the researchers concluded that the current uneven distribution of MPAs do not offer sufficient protection for marine environments.

“The mainland of the United States is not well protected” with no region reaching the 10 percent target for 2020, said Ellen Pikitch, Endowed Professor of Ocean Conservation Sciences at the School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at Stony Brook University and a co-author on the study. “The mid-Atlantic is one of the worst of the worst in that regard. We’re not well positioned and we have no time to waste.”

Indeed, the United States, through the administration of President Joe Biden (D), has committed to protecting 30 percent of the oceans by 2030. At this point, 26 percent of the oceans are in at least one kind of MPA. That, however, doesn’t reflect the uneven distribution of marine protection, Pikitch and the other authors suggested.

As much as 96 percent of the protection is in the Central Pacific Ocean, Pikitch explained. That compares with 1.9 percent of the mainland United States and 0.3 percent of the mid-Atlantic.

“We are denying the benefits of ocean protection to a huge portion of the U.S. population,” Pikitch said. “This needs to change if we want the full spectrum of marine life in U.S. ocean waters and to obtain the many benefits to human well-being that this would provide.”

The researchers in the study used a new science-based framework called “The MPA Guide,” which Pikitch helped create. This study represents the first application of this guide to the quantity and quality of marine protection around the United States.

The Guide, which was published in September in the journal Science, rates areas as fully, highly, lightly or minimally protected and is designed to bridge the gap between scientific research and government policies.

Jenna Sullivan-Stack, a research associate at Oregon State University and lead author on the paper, credits Pikitch with helping to create the guide.

Pikitch made “key contributions to this work, especially putting it in context relative to international work and also thinking about how it can be useful on a regional scale for the mid-Atlantic,” Sullivan-Stack explained in an email.

“These findings highlight an urgent need to improve the quality, quantity and representativeness of MPA protection across U.S. waters to bring benefits to human and marine communities,” Sullivan-Stack said in a statement.

Pikitch said MPAs enhance resilience to climate change, providing buffers along shorelines. Seagrasses, which Long Island has in its estuaries, are one of the “most powerful carbon sequesters” on the planet, she explained.

Pikitch suggested there was abundant evidence of the benefits of MPAs. This includes having fish that live longer, grow to a larger size and reproduce more. Some published, peer-reviewed papers also indicate the benefit for nearby waterways.

“I have seen the spillover effect in several MPAs I have studied,” Pikitch said.

To be sure, these benefits may not accrue in nearby waters. That depends on factors including if the area where fishing is allowed is downstream of the protected area and on the dispersal properties of the fished organism, among other things, Pikitch explained.

Lauren Wenzel, Director of NOAA’s Marine Protected Areas Center, said the government recognizes that the ocean is changing rapidly due to climate change and that MPAs are affected by warmer and more acidic water, intense storms and other impacts.

“We are now working to ensure that existing and new MPAs can help buffer climate impacts by protecting habitats that store carbon and by providing effective protection to areas important for climate resilience,” Wenzel said.

The researchers made several recommendations in the paper. They urged the creation of more, and more effective, MPAs, urging a reevaluation of areas with weak protection and an active management of these regions to generate desired results.

They also suggested establishment of new, networked MPAS with better representation of biodiversity, regions and habitats. The researchers urged policy makers to track areas that provide conservation benefits, such as military closed regions.

The paper calls for the reinstatement and empowerment of the MPA Federal Advisory Committee, which was canceled in 2019.

While the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration has no plans to reinstate this committee, is it “considering ways to expand the dialogue and seek advice from outside the government on area-based management,” Wenzel said.

The paper also urges the country to revisit and update the National Ocean Policy and National Ocean Policy Committee, which were repealed in 2018 before plans were implemented.

Wenzel said that the United States recently joined the High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, a multi-national effort to ensure the country commits to developing a national plan within five years to manage the ocean under national jurisdiction sustainably.

In terms of enforcing MPAs, the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries supports enforcement that fosters voluntary compliance through educating sanctuary users and promoting a sense of stewardship toward the living and cultural resources of the sanctuary, Wenzel added.

“The sanctuary system’s goal is to provide a law enforcement presence in order to deter and detect violations,” she said.

The Office of National Marine Sanctuaries works with the U.S. Coast Guard and the Department of the Interior.

In terms of the impact of the paper, Pikitch said she hopes the paper affects policies and ignites change.

“We need to ramp up the amount and quality of protection in U.S. ocean waters, particularly adjacent to the mainland U.S. and the mid-Atlantic region,” she said.