Some days, you win a close race against the best in the world by a fingernail, the way Michael Phelps did in 2008 in the 100-meter butterfly.

Other days, your team, after thousands of hours of practice, working hard, watching video and dancing on a bus — more on this later — you lose by that same margin.

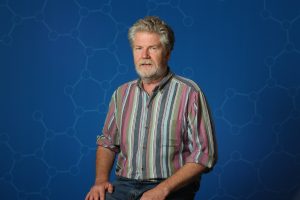

That’s how Team USA Softball’s coach Ken Eriksen, who contributed his last volunteer hour to traveling around the world on behalf of the country, felt after losing 2-0 to Japan in the gold medal game at the Tokyo Olympics.

“The difference between gold or silver is almost microscopic,” Eriksen said. “Japan had a good day.”

A turning point in the gold medal game came in the bottom of the sixth inning when American third-basemen Amanda Chidester lined a ball that hit off her counterpart at third base and into the shortstop’s mitt, who threw to second base to get a double play, ending a potential American rally from a 2-0 deficit.

“When that play occurred, that’s the first time in the game that I said, ‘This may not be our day,’” Eriksen, a 1979 graduate of Ward Melville High School said.

The head coach was pleased with the preparation and effort from a team of 15 players, including pitching legends Cat Osterman and Monica Abbott, who returned for one more chance at an Olympic medal.

“I thought we played a very good tournament,” Eriksen said from Tampa, Florida, where he has been the University of South Florida head softball coach for the last 24 years.

Outside the lines, the Olympics presented numerous challenges. Even on their way to the Olympics, it was clear this would be a unique experience, as the only people on the flight to Japan were either athletes or the military.

Once in the country, they had numerous restrictions as a result of the Delta variant.

“The Japanese wouldn’t let you do much,” Eriksen said.

The team and coaches went to the ballpark and spent much of their time at the hotel. They couldn’t go outside and socialize with other athletes. Inside the village, they had to put on their masks everywhere.

Each morning, the players and coaches had a COVID saliva test, which built anxiety as the team waited for results in the afternoon.

“There was no release of stress to go out and just relax,” Eriksen said. “Elite athletes need that pressure release and coaches need it.”

Indeed, in addition to restrictions placed on the team, the athletes regularly heard from Japanese citizens who were upset that the Olympics even took place.

“Everywhere we went, we heard protests,” Eriksen said. “It’s unnerving. You’re there in allegedly the greatest athletic event in the world and in the host country, they don’t want you. When you’re hearing voices coming over megaphones behind a police line, it’s not normal.”

To counterbalance the stress and help the team, Eriksen said he slackened the reins, giving his players the green light to get “goofy.”

“People think of athletes as having ice in their veins. They are human beings.”

— Ken Eriksen

Led by infielder Valerie Arioto, 32, the team danced on the bus. Arioto did the “greatest rendition of Cher” and Kelly Clarkson, Eriksen said. The head coach also allowed the team to listen to music while practicing, giving them a chance to blow off steam while preparing for upcoming games.

Mental health

Eriksen said the softball team had already focused on the mental health aspects of the game, which gymnast Simone Biles brought to the world’s attention when she withdrew from the team and several individual events.

“We’ve been ahead of the curve on this for three or four years,” Eriksen said.

While people talk about softball and baseball as games of failure because a batter is considered successful if he or she gets on base once in three tries, Eriksen said the softball team describes the experience as a “game of opportunity,” by defining successes in ways other than batting averages.

Eriksen is grateful to Biles and Japanese tennis player Naomi Osaka, who withdrew from Wimbledon rather than face questions from the media, for raising the issue of mental health for athletes.

“People think of athletes as having ice in their veins,” he said. “They are human beings. The pressure on anybody that wears a U.S. uniform … is almost unfair.”

The rest of the world has improved in numerous sports, including softball, in part because American coaches have helped train them, Eriksen added. Through the Olympics, American players compete against their college roommates or coaches who worked with them earlier in their careers.

After the gold medal game ended in heartbreak for players who put everything they had into the game, Eriksen said he shared a few words with the team.

“This game will not be the toughest they’ll ever play,” he recalled. “The toughest game will start tomorrow: the rest of their life.”

He encouraged players to call him for any future support.

Having been an assistant coach with the gold-medal winning team in Athens in 2004, Eriksen recognized that the game fades quickly.

“Within five minutes, you have the realization that it’s over and the climb is the most exhilarating part,” he said.

Eriksen was pleased to have the support and leadership of 38-year-old Osterman and 36-year-old Abbott, who served as inspirations to their teammates. He described the two pitchers as the Nolan Ryans of their era.

“What God gave these people is absolutely rare,” Eriksen said, as they have maintained their athleticism well into their 30s.

Accumulated wisdom

After all his years on the diamond, first as a baseball player at Ward Melville and in college at USF, and then as a coach, Eriksen shared a few thoughts.

When he was hired, his athletic director at USF told him never to get in a conversation with parents because he’ll always lose. Twice in his career, he removed players from the team because their parents questioned him about playing time.

As for being around men’s and women’s teams, he suggested a difference among athletes of each gender.

“Women have to feel good to play good, men have to play good to feel good,” he said.

In his coaching career, he recalled one moment that mirrored a scene from the Kurt Russell movie “Miracle,” in which the actor played Coach Herb Brooks from the 1980 ice hockey team that defeated the Russians amid the Cold War in Lake Placid.

Before tryouts ended, Russell gave a stunned Olympic hockey league director his list of players.

In 2019, Eriksen said he, too, handed the Olympic softball league director a list of the 15 players who would be on the team before tryouts ended.

Eriksen said he is comforted by his decision to retire from coaching Team USA.

“If I never get on an airplane again, I’ll be okay,” he said. “Sometimes, it’s good to wake up in your own bed, drink coffee on the back porch and listen to the birds.